Charles Gounod kept working during the final year of his life. He suffered a variety of afflictions and ills but composed sacred music and penned his memoirs and essays. When he returned home from playing the organ for Mass at his local church on 15 October 1893, he suffered a stroke. After being in a coma for three days Gounod died on 18 October, at the age of 75. The composer, anticipating his death, had called it “the last modulations resolving to the tonic of the eternal concert.”

Charles Gounod: Messe solennelle de Ste. Cécile, “Repentir”

Health Problems

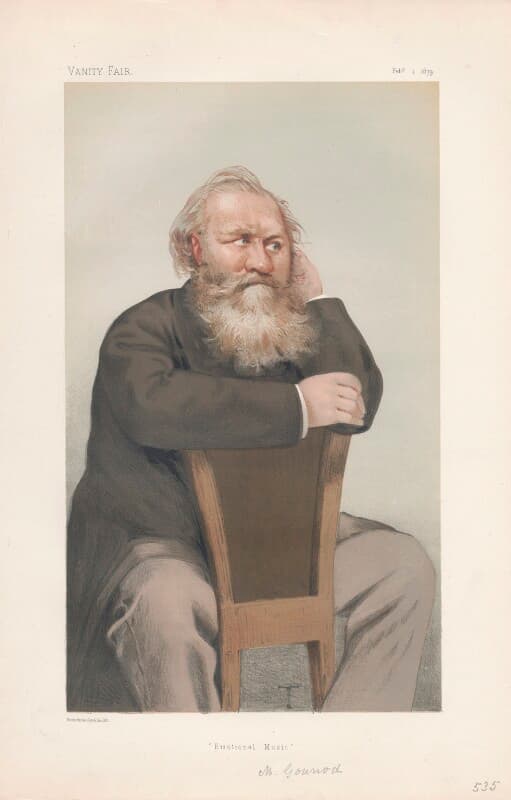

Charles Gounod

In 1891, Gounod recovered from an extended attack of bronchitis only to suffer from heart trouble and temporary paralysis of one side of his body. His eyesight began to fade and his right arm was affected by sciatica. And still, he went on composing music, writing the suite les Drames sacrés, a sequence of eleven tableaux for a play produced in 1893. His mind was alert though his body faltered. “I feel as young in my mind as I was at the age of twenty,” he complained.

Gounod lived in seclusion at Saint-Cloud and he continued his lifelong study of the Bible. He was unwilling to give up his art completely, and started to investigate the problem of tonality and suggested a solution in an essay entitled “The constitution of the scale explained by the division of the circumference into forty-eight equal parts.” On occasion, he was getting too tired for clear thought, and his remarks took on a surrealist quality. His doctors eventually prevented him from working, so he strolled in the garden wearing his black suit and a Panama hat.

Charles Gounod: Préludes et fugues pour l’étude préparatoire au Clavecin bien tempéré de Jean Sébastien Bach (Alessandro Mercando, piano)

Gounod’s Death and Funeral

News of his death was quickly reported around the world, and commentators were searching to place his oeuvre within the context of French music. A major publication wrote, “While the death of Gounod will arouse general regret, it cannot be accounted a serious loss to music. Gounod’s day was done and his career ended. It had been such a long time indeed since he produced an important work, and he had ceased to be anything but a sterile monument to his own notable past.”

Gounod did warrant a state funeral and it was held at L’église de la Madeleine in Paris on 27 October 1893. Among the pallbearers were Ambroise Thomas, Victorien Sardou and the future French President Raymond Poincaré. Thumping his nose at all his detractors, Gounod had expressly demanded that the music at his service was to be entirely vocal, sounding no organ or orchestral accompaniments. In fact, the only music performed on the occasion was Gregorian plainchant.

Charles Gounod: Te Deum (Les Choeurs de la Madeleine; Philippe Brandeis, organ; Joachim Havard de la Montagne, organ/cond.)

Assessment and Influence

Tomb of Charles Gounod at Auteuil Cemetery, Paris

On the day of his death, Gounod’s good friend and disciple Camille Saint Saëns summed up with a few well-chosen words the chief features of Gounod’s career. “At the beginning he was misunderstood, followed only by a faithful few; and, without ever deviating from the line which he had marked out for himself, he gradually attained success, fame, and popularity. Nevertheless, he had to contend against an incessant hostility. In the first place, he came in conflict with the ‘light horse’ of comedy opera; next, with the Italian coterie; finally, with the German clique.”

Gounod clearly left his mark on the course of French music, but he rapidly fell from favour. According to Ravel, Gounod was the real founder of mélodie in France, and he was without doubt one of the most prolific composers of religious music in France in the 19th century. And let’s not forget that Gounod the opera composer decisively influenced Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns. For Bizet “melody alone counted in music.” As he wrote to a friend, “recently I heard a modern work at a big concert. It had lots of notes and the orchestra spread itself in great waves of sound. Well, I’d have given anything to hear a melody, however short.”

Charles Gounod: String Quartet No. 3 in A minor

The Role of the Artist

Gounod the artist resisted the post-Wagnerian fractured climate towards the end of his life. He stubbornly upheld the privileged role of the artist in society. Any musical expression of beauty, so he argued, would be intuitively grasped by listeners no matter what ideological camp they belong to. He hated the ideas of realism, doctrines of progress, and particularly self-justifying polemics.

“The work of the artist,” so he wrote, “stood or fell on its own merits.” And since he refused to follow the implications of Wagner’s musical style, he quickly became the subject of hostilities and scorn. For Claude Debussy, “Gounod, for all his weaknesses, is necessary. His art represents a moment in French sensibility. Whether one wants to or not, that kind of thing is not forgotten.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter