It took Richard Wagner the better part of 26 years to complete Götterdämmerung (Twilights of the Gods). This final opera in the Ring cycle was originally called “Siegfried’s Tod,” and the resources and stamina demanded by the work from both singers and orchestra, combined with the sheer lengthy and theatrical potency, makes it one of most daunting yet rewarding undertakings in the operatic repertory. It premiered at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus on 17 August 1876 as part of the first complete performance of the entire Ring.

Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung “Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey”

Valhalla in Flames

Richard Wagner, 1876

To be sure, Götterdämmerung has one of the most epic endings in opera. Hagen, who murdered Siegfried, jumps into the water to pursue the ring. To the sound of the Curse motif, the Rhinemaidens drag him down into the depths of the river and raise the ring in triumph. From the ruins of the palace, which has collapsed, the crowd watches a burst of firelight as it rises into the sky. It eventually illuminates the hall of Valhalla, where gods and heroes are assembling.

The Valhalla motif combines with the motifs of the Rhinemaidens and the Glorification of Brünnhilde. To the sounds of the motifs of the Twilight of the Gods and the Glorification of Brünnhilde, Valhalla is engulfed in flames. The gods are consumed in flames and the curtain falls. At the very end of the work, emerges the sound of the redemption-through-love motif and the long-awaited end of the gods has come to pass.

Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung “Mehr gabst du, Wunderfrau” (Daniel Brenna, tenor; Gun-Brit Barkmin, soprano; Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra; Jaap van Zweden, cond.)

Path to the Ring

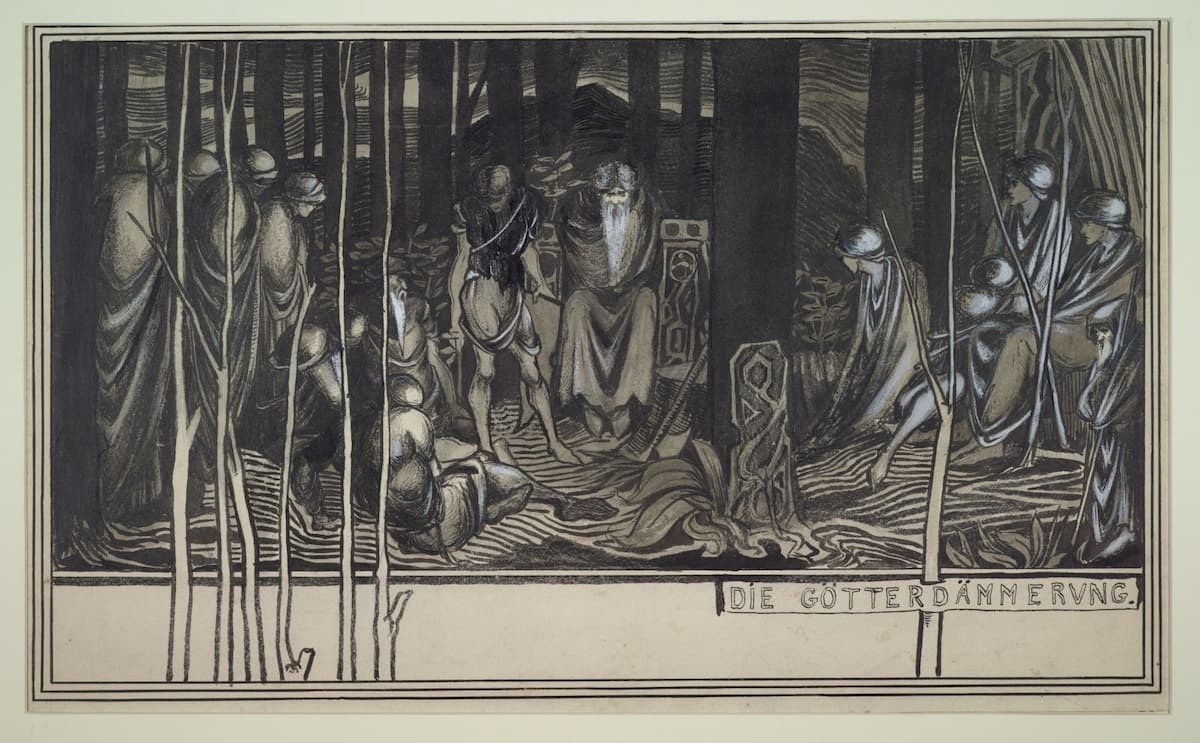

Aubrey Beardsley’s “Die Götterdämmerung”

Although it might be said of much of Wagnerian opera, but Götterdämmerung is a rather difficult work to get a handle on. It introduces a number of completely new characters, which isn’t really a great idea when one is telling the end of an epic story. The music also fits somewhat uncomfortably with the other parts of the Ring, as the leitmotif saturation of previous works gives way to much more conventional operatic gestures. After all, we find heroic duets, massive choruses and plenty of high C’s.

It is worth remembering, however, that the text of Götterdämmerung was the first Ring text Wagner put on paper. Originally, he intended it to be a stand-alone work, and by 1848 he had completed a prose draft for a three-act opera with a two-scene prologue. Wagner immediately began a process of revision, and he began to doubt the wisdom of writing an opera on such an obscure subject. All we know with certainty is that after Wagner completed the libretto of Siegfried’s Tod, he put it aside and turned his attention to other matters.

Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung “Hagen’s Wacht”

Themes

Reproduction of the set design by Max Brückner of the final scene from Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, showing Valhalla on fire

We tend to think that Wagner’s monumental Ring tetralogy is simply a strange story involving German mythological heroes. It does deal with friendship, love, and fate, but it is also about the economic, social, and ecological changes and the crisis of values experienced in the past two hundred years. The original state of nature is idyllic and harmless, but the imposition of laws and orders such as marriage, property, and money are evil. It is through love that human beings can live harmoniously with each other, and that love will hold it all together.

Wagner addresses several non-musical themes as well, including the “rejection of love and the pursuit of power as embodied in the possession of the ring (Alberich and Wotan), and the violation of the natural order through imposed contractual law (Wotan’s spear).” Possession of power and gold command love at every level of The Ring.

Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung “Hoiho? Hoihe!” (Eric Halfvarson, bass; Daniel Brenna, tenor; Yang Shen, bass-baritone; Bamberg Symphony Chorus; Hong Kong Philharmonic Chorus; State Choir Latvija; Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra; Jaap van Zweden, cond.)

Reception

Final scene from Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

The much-anticipated 1876 premiere was a huge success, and it has engendered scholarly and popular critique of unprecedented proportions. One of the monumental artefacts of the 19th century, it seldom fails to provoke controversy whenever and wherever it is performed. Wagner’s tetralogy offers an opportunity to confront “entrenched political, theological and cultural views, while simultaneously beholding its rare beauty and raw power.”

The complex dramaturgy is rather confusing without Wagner’s music. It is the musical Leitmotif, which symbolically refers to characters, actions, objects, and ideas, that sustain an evolving coherent narrative from the first note to the last. The thematic materials offer a kaleidoscope of rhythmic, melodic, timbral, and tonal variations that create their own world for the listener.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter