Marin Alsop

Much has been made of Marin Alsop’s appointment as Music Director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in 2007. And rightfully so, as she was the first woman to hold this position with a major American orchestra. Her achievement forever raised our collective level of consciousness and made it impossible to ever think of a conductor in the same way again. Alsop has followed up with other firsts, including first woman to be the principal conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in England and the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra in Brazil, and the first and only conductor to receive a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called Genius Award. And she is currently the principal conductor of the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, making her the first woman to ever lead a Viennese orchestra. These significant musical, cultural, and social milestones don’t happen every day, and they certainly don’t happen by accident. “Conducting,” Alsop suggests, “is a long journey of perseverance, and if you’re going to waver at every corner, you’re never going to make it… It takes all kinds of skills and disciplines, and plenty of inspiration.”

Marin Alsop Conducts Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, “Death of Tybalt”

The young Marin Alsop

Born in New York City on 16 October 1956, Alsop credits much of her success to the inspiration she received not only from her parents Ruth E. Condell and Keith Lamar Alsop, both professional musicians but also from Leonard Bernstein. She remembers seeing one of Bernstein’s famed Young People’s Concerts at the age of nine, and “from the moment he came out on stage and began speaking to the audience,” she recalls, “he shared his charisma and his obvious joy for what he was doing. And from that day on, I knew I wanted to be a conductor.”

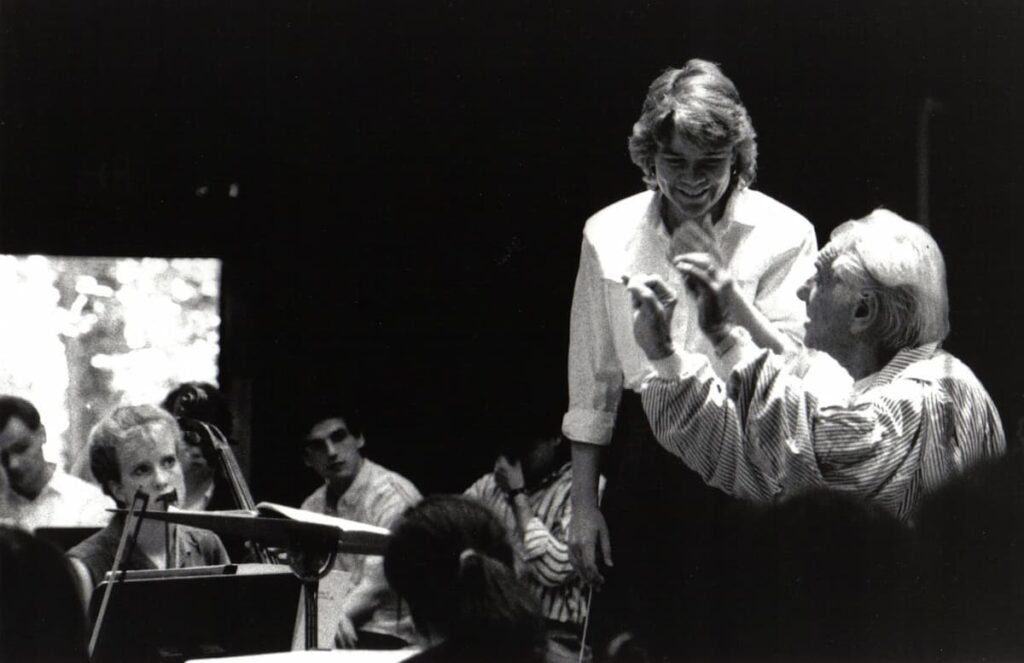

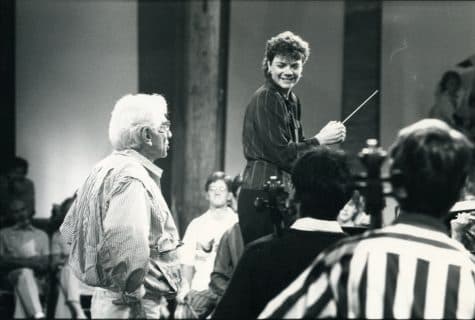

Leonard Bernstein and Marin Alsop © Walter Scott

Alsop would finally meet her hero and future mentor at the Tanglewood Music Center in 1989, and she still considers her apprenticeship “one of the greatest experiences of her life.” She remembers, “he exceeded all of my expectations—he was so generous, so loving, and so caring of all of his students, but I felt especially of me. Maybe each of his students felt that way—that was his gift. One of the most valuable things I learned from him was the idea of telling stories through music. He was a great storyteller. If he didn’t know the story of a piece, he’d make it up. He was always inventing stories because he understood that we, as human beings, needed a story… and we need a moral to the story.”

Marin Alsop Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, “Eroica”

Leonard Bernstein and Marin Alsop © Bernadette Wegenstein/BMOREART

Alsop remembers Bernstein as the model for the socially responsible, inclusive, and generous Maestro, and that he spoke about music with incredible passion. According to Alsop, “he had an overriding desire to share his excitement about music, one he absolutely wanted everyone to have.” In sharing Bernstein’s vision, Alsop has become an inspiring and powerful voice on the international music scene, “a Music Director of vision and distinction who passionately believes that music has the power to change lives.” She is recognized across the world for her innovative approach to programming and for her deep commitment to education and to the development of audiences of all ages. Alsop initiated the “OrchKids” program designed to promote music education for underprivileged young people in Baltimore, and she brought her passion to the São Paulo Symphony. And while the São Paulo audience may still be learning to appreciate classical music, for Alsop the experience of challenging them is a meaningful one. “Besides the gorgeous concert hall,” she explains, “I was so impressed with the exponential growth in the orchestra over just a couple of days. They were hungry for hard work and had enormous potential. And they bring a fresh attitude to the orchestral pit that is no longer found in Europe and America.”

Hans Werner Henze: Nachtstücke und Arien – Nachtstück I (ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

Marin Alsop with Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo © Gilberto Marques /A2img

Alsop has become an enthusiastic mentor for young conductors, and she frequently explains how gestures can be interpreted. Alsop said, “it’s fascinating because everything we do as conductors is about body language. And body language is interpreted differently when it comes from a woman or from a man—the same action, the same gesture… And so what I am trying to get across to the students I am working with was that we need to have a constant awareness of what we’re doing so that we can almost degenderize—if that’s a word—what we’re doing and make it only about the music because a gesture like that, you know, which is kind of frilly, would be seen as sort of weak, maybe a little bit submissive if a woman does it. If a man does it, it probably will be interpreted as being sensitive. And this is just the world we happen to live in. I’m just trying to deal with the world, the real world, and how to express the music gesturally so that there is no gender association with it. It’s only about the music.” Alsop also loves to champion the works of contemporary composers, “because it brings me close to the creative process.” As she explains, “I am not a creator, I am always the re-creator. So I am extremely respectful and always in awe of the composers. So working with living composers is a dream come true because I start to understand their inspiration, their motivation, and the narrative behind their pieces.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Marin Alsop Conducts Dvorák’s Symphony No. 9