Gioachino Rossini, 1865

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) was celebrated throughout Europe, and his operas became fixtures on the most prestigious stages around the world. However, things weren’t all that cheerful in terms of his health. An infection with gonorrhea, the result of his early adventures in various brothels, started to cause problems when he was 15. In fact, that infection was probably the cause of many later medical complaints. The famous physician Carl Gustav Carus examined Rossini in Venice in 1841, but he was unsuccessful in his hemorrhoid treatment with the help of leeches. In 1843 Rossini traveled to Paris to consult the famed urologist Jean Civiale, “who advised to perform daily urethral dilatations with a Benique sound for 15 to 20 minutes, and to irrigate his urethra with a mixture based on sweet almonds.” Rossini would continue this particular treatment for the rest of his life.

Gioachino Rossini: Petite Messe Solennelle

Rossini, 1850

Rossini also appears to have suffered from emphysema-bronchitis and related heart problems, and was troubled by melancholic depression causing sleeplessness and suicidal tendency. In a letter of 1854 Rossini wrote of ‘the deplorable state of health in which I find myself for five long months, a most obstinate nervous malady that robs me of my sleep and I might say almost renders my life useless.” Although he did “put reins on his passion for women and stopped the excessive consumption of alcohol and spicy food” because of chronic abdominal problems, his health did not improve. Hoping that French doctors might be able to affect some cures, and he relocated to Paris in 1855. Rossini “presented obvious symptoms of metabolic syndrome with morbid obesity, and in 1856 had a stroke with partial paralysis.” Doctors diagnosed a rectal carcinoma in 1868, and the French surgeon Auguste Nélaton performed an operation under chloroform anesthesia. The famed imperial personal physician of Napoleon III probably operated with a poorly disinfected instrument, and following a second operation Rossini died on 13 November 1868.

Gioachino Rossini: “Mi lagnerò tacendo” (Jessica Pratt, soprano; Vincenzo Scalera, piano)

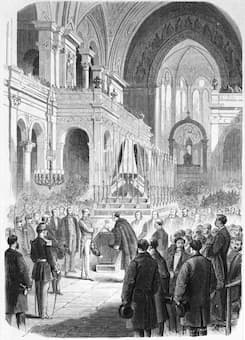

The Parisian illustrated newsweekly L’Illustration documented Rossini’s funeral proceedings – The sprinkling of holy water in the Church of the Holy Trinity

Rossini’s funeral took place in Paris’ newest and largest church, Sainte-Trinité. It was a cold and gloomy day, “and among the envied holders of tickets for the interior of the church, ladies shivered in the precincts for two hours before the doors opened. It required a very large military and police force to clear the way for the funeral procession from the Madeleine to the Trinité to prevent the populace from blocking up the approaches to the latter church.”

The funeral procession leaving Church of the Holy Trinity

In the end, almost four thousand people crammed into the church, including “all the familiar faces of French and Italian Opera… A guard of honor of the Fifty-First Regiment lined the nave… and although the majority of the spectators had come to see a spectacle and were laughing and talking, many had evidently solemn thoughts befitting the occasion.” Several newspapers reported that the event was more like “a festive concert, or an opera, the crowds went there to hear great singers perform, and to pay tribute to a man who had lived beyond his time.” The Parisian illustrated newsweekly L’Illustration even published a visual record of funeral proceedings.

Gioachino Rossini: Péchés de vieillesse, Vol. 9: Album pour piano, violon, violoncelle, harmonium et cor: No. 4. Un mot à Paganini, “Élégie” (Massimo Quarta, violin; Alessandro Marangoni, piano)

Gioachino Rossini: Péchés de vieillesse, Vol. 8: Album de château: No. 9. Tarantelle pur sang avec traversée de la procession (version for choir, harmonium, piano and clochette) (Ars Cantica Choir; Alessandro Marangoni, harmonium/piano; Marco Berrini, bells/cond.)

Gioachino Rossini: Péchés de vieillesse, Vol. 11: Miscellanée de musique vocale: No. 10. Giovanna d’Arco (Lilly Jørstad, mezzo-soprano; Alessandro Marangoni, piano)

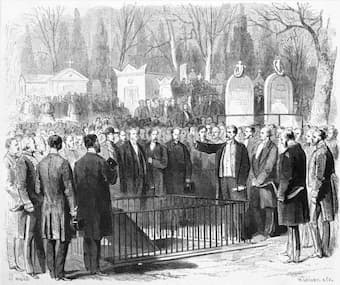

Lowering of the coffin into the vault of the city, in Père-Lachaise Cemetery

Thousands of spectators lined the route from Sainte-Trinité to Rossini’s temporary resting place in Père-Lachaise. Mourned throughout Europe, The Times wrote, “Rossini was sought out and courted, not merely on account of his fame as a composer, but for his wit, his humour, his amiability, and general goodness. With him has departed one of the most remarkable geniuses and one of the kindliest spirits of the nineteenth century.” In terms of legacy, however, commentators had to come to terms with the fact that Rossini had spontaneously decided to retire at the height of his operatic career in 1829.

Giuseppe Cassioli: Monumental Tomb of Gioachino Rossini

The compositional hyperactivity of his early life was now followed by almost four decades of inactivity. Although opera houses frequently begged him to compose new works, Rossini would graciously decline all offers. Once he took up composition again, “it functioned as a musical exhumation” that foreshadowed a movement of neo-classicism. “The tensions engendered by Rossini’s precarious status as both living and dead, and his nostalgic relationship to the past… can be heard in his late compositions,” the ones I have featured in this article. Rossini’s final resting place is at S Croce in Florence, as his widow Olympe persuaded the government to permit Rossini’s remains to be transported to Italy in 1887.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gioachino Rossini: 3 Chœurs religieux