Sean Shepherd: Express Abstractionism

In the 20th century, there was a deliberate effort in art to get away from the literal, the real, and the representative and into the realms of the mind. Abstract Expressionism was just one of those forms – spontaneity and gesture were important, coming from the earlier Surrealist school where automatism, or art from the unconscious mind, held sway.

American composer Sean Shepherd took the art of 5 artists of the Abstract Expressionist school as the source of inspiration for his 2017 work Express Abstractionism. A co-commission of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, the work takes a tongue-in-cheek look at the products of the school.

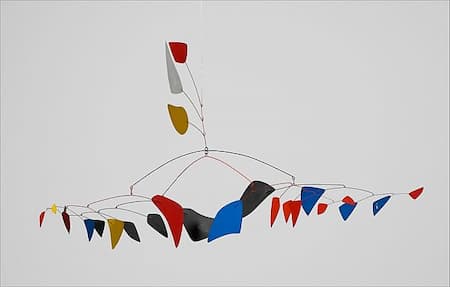

The first movement takes an unspecified work by Alexander Calder for its inspiration. The movement ‘dense bubbles, or: Calder, or: the origin of life on earth,’ takes Calder’s mobiles with their constantly moving nature and translates it into musical terms of not blocks of colour but blocks of instrumental combinations that move and overlap.

Calder: Four Directions (1956) (Met Museum)

Sean Shepherd: Express Abstractionism – I. dense bubbles, or: Calder, or: the origin of life on earth (Boston Symphony Orchestra. Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Movement II, ‘Richter, or: the rainbow inside a bolt of lightning,’ uses the art technique of German artist Gerhard Richter as its source. Richter’s style of applying paint to the canvas with a squeegee or a board to make a texture that has direction but that also has an uneven density is represented in music by short gestures that are alternated with dense patterns of repeated sound. Just as Richter’s surfaces are smooth but ruptured, so Shepherd’s music moves from relative calm to repeated activity.

Gerhard Richter creating a squeegee work

Sean Shepherd: Express Abstractionism – II. Richter, or: the rainbow inside a bolt of lightning (Boston Symphony Orchestra. Andris Nelsons, cond.)

The third movement takes two artists with very different styles, Wassily Kandinsky and Lee Krasner. Kandinsky’s works are colourful and bright, often relying on geometric forms for their solidity. Composition 8, for example, incorporates styles of the Russian avant-garde with overlapping flat planes and clearly defined shapes. For Kandinsky, the circle was important, saying ‘it combines the concentric and the eccentric in a single form and in equilibrium. Of the three primary forms, it points most clearly to the fourth dimension.’

Kandinsky: Composition VIII (1923) (New York: Guggenheim)

Lee Krasner’s paintings on the other hand, are much more dynamic. The full canvas is covered with shapes that sometimes seem like calligraphy. In her late style of the 1970s, abstract forms were pared with strongly contrasting colours.

Krasner: Palingenesis (1971)

In one sense, the two artists couldn’t be more different and yet, in the music, we can hear a relationship. One writer saw this in the music as a division in style: ‘The movement’s scale melodies denote Krasner’s looping lines; brass and percussion suggest the solidity of Kandinsky’s forms.’ But you could also read it the other way – the loops of Kandinsky and the solidity of Krasner.

Sean Shepherd: Express Abstractionism – III. Kandinsky, and: marble, and: Krasner (Boston Symphony Orchestra. Andris Nelsons, cond.)

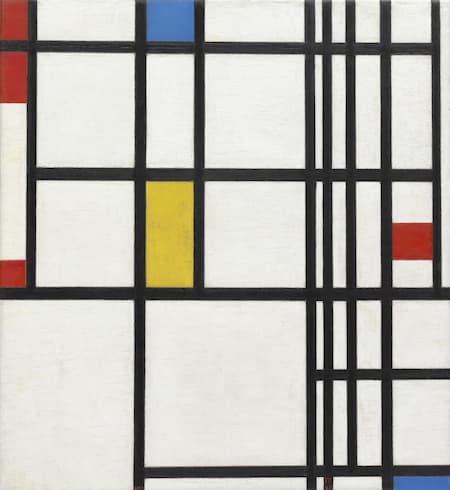

The last movement is about the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian. His late grid paintings are represented musically in an austere manner in the music. Shepherd’s still and balanced network of materials could just as easily be the surface of a Mondrian work.

Mondrian: Composition in Red, Blue, and Yellow (1937-42) (MoMA)

Sean Shepherd: Express Abstractionism – IV. the sun, or: the moon, or: Mondrian (Boston Symphony Orchestra. Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Shepherd’s music invites us to take a different look at Abstract Expressionism. Instead of standing outside the work, seeking to find what the artist saw, he takes us into the work and gives us musical representations that give us a deeper understanding of a work of visual art.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter