Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) was a Dutch painter who expanded the modern abstract painter’s vocabulary by reducing his colour choices and moving to geometric elements to express his art. He is now regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century and an ideal in the concept of Modernism. He declared in 1914: ‘Art is higher than reality and has no direct relation to reality. … Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man.’

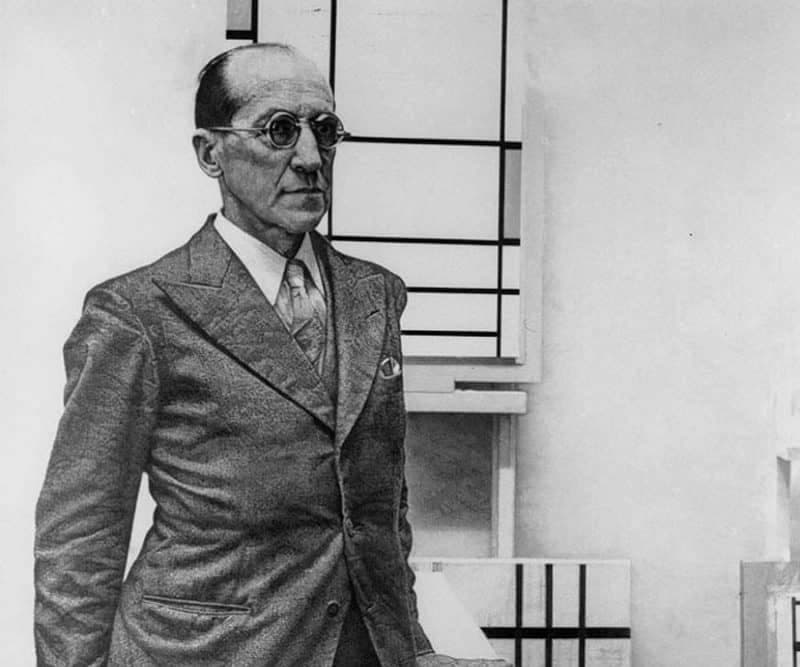

Piet Mondrian in front of Composition No. 10

He was an artist as a child, working under the tutelage of his father, who taught drawing, and his uncle, part of the Hague School. At age 20, he entered the Academy for Fine Arts in Amsterdam and worked in an impressionistic style.

Around 1905, he began experimenting with the abstract, although his paintings were still rooted in nature. He began following the theosophical movement of Madame Blavatsky and the anthroposophy movement of Rudolf Steiner, developing his own artistic ideal of neoplasticism.

In his two pictures, Still Life with Ginger Pot I and II, done a year apart, we can see him move from Cubism into an early experiment with triangles and rectangles.

Mondrian: Still Life with Ginger Pot I, 1911 (Gemeentemuseum den Haag, Hague, Netherlands)

Mondrian: Still Life with Ginger Pot II, 1912 (Gemeentemuseum den Haag, Hague, Netherlands)

In 1911, Mondrian moved to Paris and the influence of Cubism hit him immediately. He returned to The Netherlands in 1914, and was stranded there by WWI, he began moving away from representational painting and began developing what would become his signature style of horizontal and vertical black lines creating squares and rectangles to be filled with colour.

After the war, he returned to Paris for 20 years, working in a world of complete abstraction.

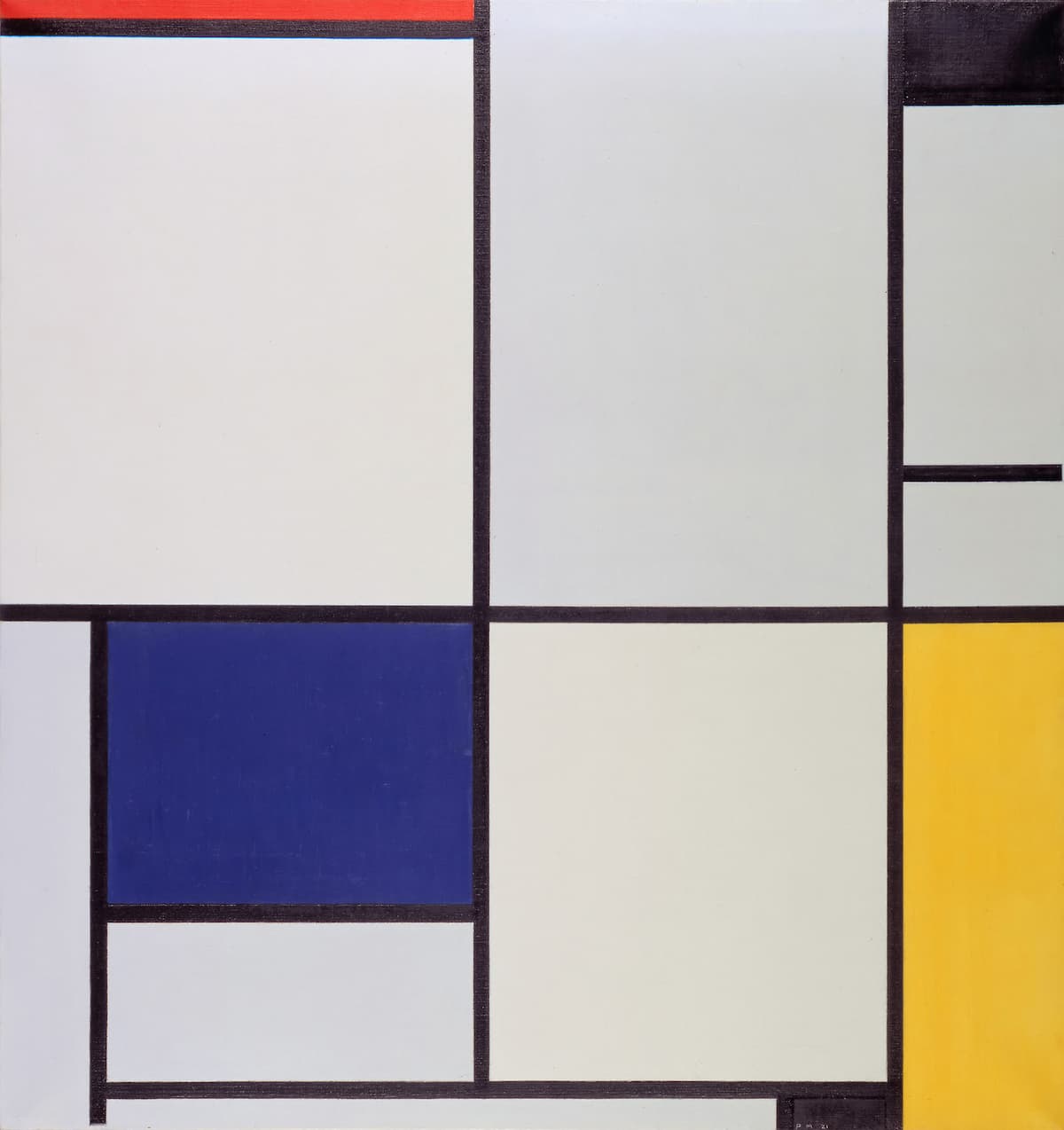

Mondrian: Tableau I, 1921, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

The war again interrupted his life, driving him in 1938 from Paris to London and in 1940, from London to New York. After the relative spare style seen in Tableau I above, his canvases got busier. They become almost like maps in their appearance. After he arrived in New York, he augmented his black vertical and horizontal lines with the use of thicker lines and colour. Some of his works left incomplete at his death show the use of painted paper tape so he could experiment with the placement of his lines.

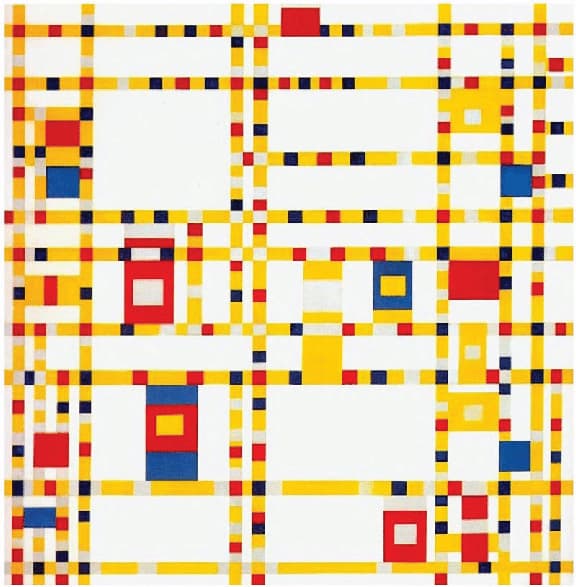

His 1942–43 work Broadway Boogie-Woogie now breaks up the solid black lines into lines with colour, banded almost like a snake, and the formerly solid colour blocks have other colours in their centres. The bright colours seem to jump off the page and the painting makes it seem to move and shimmer as you look at it.

Mondrian: Broadway Boogie-Woogie, 1943 (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

The Music Term ‘Boogie-Woogie’

The title of the piece incorporates the music term ‘boogie-woogie’ – it was a term associated with blues music and may have started as early as the 1870s, but came into its own in the 1920s. As first a piano genre, it eventually gained players until it became part of big-band music in the 1930s and 40s.

It influenced jazz and then classical music, such as in this boogie-woogie piece by Morton Gould.

Morton Gould: Boogie Woogie Etude (Shura Cherkassky, piano)

Jim Parker: The Golden Section – VI. Broadway Boogie-Woogie

When we look at music influenced by Mondrian’s art, we have some very different responses. British composer Jim Parker’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie, the seventh movement of his larger work on art called The Golden Section.

Jim Parker: The Golden Section – VI. Broadway Boogie-Woogie (Wallace Collection)

Christopher Fox: Broadway Boogie

British composer Christopher Fox had a different approach to the painting. Where Mondrian saw his work as part of the aesthetic of ‘the destruction of natural appearances’, Fox made a parallel by using Edgard Varèse’s Octandre as the natural work to be deconstructed. The work is for 1 live oboe and 2 pre-recorded oboes, all of which are working at different tempos.

Christopher Fox: Broadway Boogie (Christopher Redgate, oboe; Ensemble Expose)

Richard Aldag: Serenade, “Broadway Boogie Woogie”

American composer Richard Aldag nicknamed his Serenade as Broadway Boogie-Woogie not after the painting but because of the comment that the work sounded like New York.

Richard Aldag: Serenade, “Broadway Boogie Woogie” (Gina Gulyas, flute; Matthew Boyles, clarinet; Rachel Patrick, violin; James Jaffe, cello; Ian Scarfe, piano; Divesh Karamchandani and Andy Meyerson, percussion; Richard Aldag, cond.)

Mondrian’s fascination with boogie-woogie music started on the day he arrived in New York in 1940, seeing in its dynamic rhythm and how it destructed the core melody as the same as his own style’s destruction of natural appearance. Dance to the music…or dance to the art. It’s all there.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter