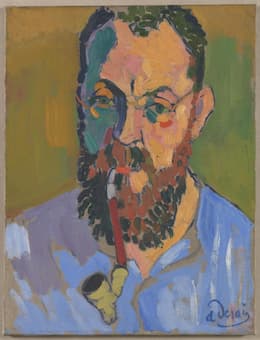

André Derain: Henri Matisse (1905) (London: Tate)

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was known for his fluid style and his use of colour and it’s those two attributes that French composer Éric Montalbetti (b. 1968) chose as the inspiration for the three vocalises for voice and clarinet he created in homage to the French master, written in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth.

Writing for voice and clarinet pairs instruments that were always thought to be close – although in its earliest stages, the clarinet was used as a more manageable trumpet, by the time of Mozart, the sound had mellowed. Mozart considered the sound of the clarinet to be the closest in quality to the human voice. In 1785, he complimented Anton Stadler’s playing, particularly the high registers, saying ‘Never should I have thought that a clarinet could be capable of imitating a human voice so deceptively as it was imitated by [you].’ Anton Stadler (1753-1812) was the instrumentalist for whom Mozart wrote his Clarinet Quintet, K. 581 and Clarinet Concerto, K. 622.

Éric Montalbetti © David Wagnières

In his setting, Montalbetti gives no words to the vocalist but does provide guidance with phonemes. The composer notes: ‘…there is no text: the singer vocalises freely on phonemes indicated merely as one proposal among other possible ones to construct the colour of the sounds, but without any signified meaning except the first or last word of each melody.’

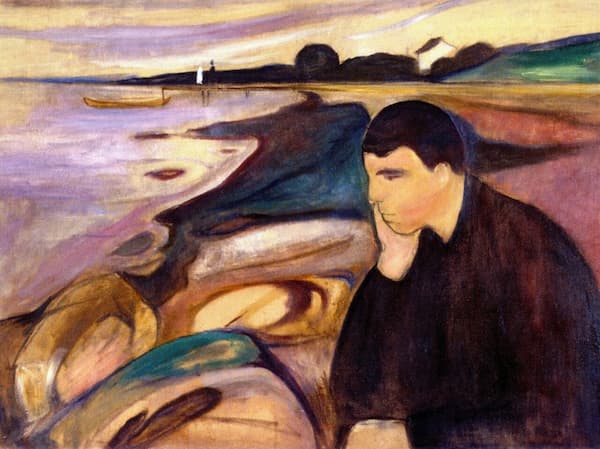

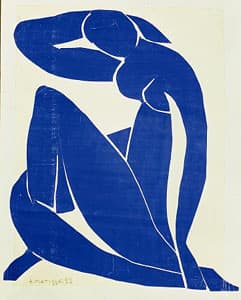

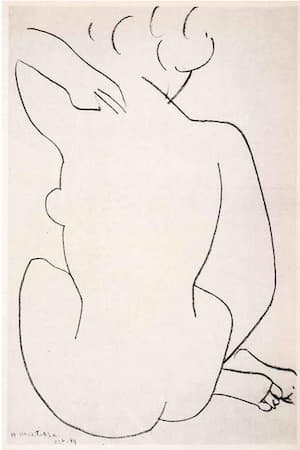

The first movement, Nu (Nude), is about the simplicity of line in Matisse’s drawings of the figure. The voice and clarinet also ‘symbolise the relationship between the artist and his model.’

Matisse: Blue Nude II (1952) (Pompidou Centre, Paris)

Even as just a line drawing, the simplicity of Matisse’s line come through – he portrays the figure with a minimum of lines.

Matisse: Seated Nude Back View (1958)

Éric Montalbetti: Hommage à Matisse – No. 1. Nu (Delphine Haidan, mezzo-soprano; Pierre Gisson, clarinet)

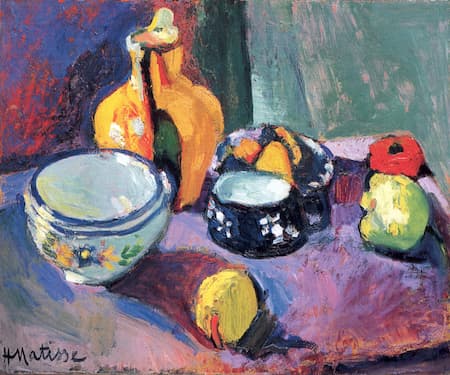

The second movement seizes on the other attribute of colour and transforms it into light. Éclat (Radiance) refers to both its reflection of the sun and an inner glow.

Matisse: Vase with Fruit (1901) (St. Petersburg, Hermitage)

The windows for the Chapel of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, seem to gather in the light from the outside and amplify it for the interior.

Matisse: Chapel of Saint-Paul-de-Vence (1951)

Éric Montalbetti: Hommage à Matisse: No. 2. Éclat (Delphine Haidan, mezzo-soprano; Pierre Gisson, clarinet)

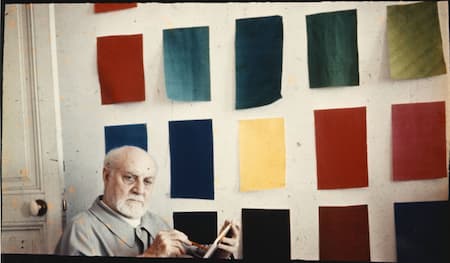

The last movement, Couleur (Colour), uses Matisse’s words to show how layering colour was how he created his works: ‘I applied my colour; it was the first colour on my canvas. I added a second colour, and then, when this second colour did not seem to match the first, instead of changing it I applied a third colour, intended to reconcile them. I then had to continue in this way until I had the feeling that I had created a complete harmony in my canvas, and that I was relieved of the emotion that had made me embark on it.’

In this picture of Matisse in front of gouache-painted paper, analysists note that there were, for example, at least 17 different versions simply of orange.

Henri Matisse and colour samples

In his large-scale works, such the paper cuts of The Parakeet and the Mermaid, we can see how the contrast of colour and no colour (the white background) grabs our eye differently on each panel and how the oranges, in fact, are not all alike.

Matisse: The Parakeet and the Mermaid (1952) (New York, MOMA)

This is the longest of the movements of the work and stands for how important colour was to Matisse and Montalbetti uses the low timbre of the mezzo voice as almost a backdrop for the scalar movement of the clarinet.

Éric Montalbetti: Hommage à Matisse: No. 3. Colour (Delphine Haidan, mezzo-soprano; Pierre Gisson, clarinet)

The work was given its premiere with Delphine Haidan and Pierre Génisson in 2019 at the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, the painter’s home town, in partnership with the festival Les Musicales de Cambrai.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter