The J. Paul Getty Museum, aka the Getty, is housed in Los Angeles. Founded by Jean Paul Getty, the museum opened in 1974. Getty’s collecting had started in the 1930s, after the depression hit, when European art was readily available on the market. In the 1950s, his collecting interests expended to the Greco-Roman period, particularly of sculpture. To house this, he built the Getty Villa, inspired by the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum. Today, the Getty Villa houses the Greek, Roman and Etruscan holdings, while the larger Getty Center in Brentwood holds the rest of the collection.

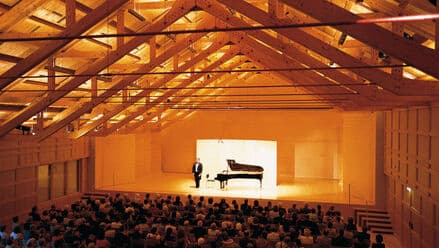

We’ll start with a cup from 500 BCE. Attributed to the Greek artists Psiax, who was active about 525 – 510 BCE, the cup was designed for drinking at a symposium. This form is very rare and was produced by potters only in the later 500s BCE. The lack of a flat bottom and the nipple at the base meant that the drinker would have to drain the cup before it could be put down.

On one side of the cup is a woman playing the double aulos, two reed pipes played together with one mouthpiece. Each hand covered the holes for each pipe separately.

Psaix (attributed to): Attic Black-Figure Mastos, Side A, ca 520-500 BCE (Getty Villa)

On the other side is a woman with a branch and an ivy sprig. These two pieces, combined with the animal skin she wears over her shoulder, defines her as a Maenad, one of the women followers of Dionysus. When Orpheus returned from the underworld, after his unsuccessful retrieval of Euridice, he was killed by the Maenads for refusing to entertain them while in mourning for Euridice.

Psaix (attributed to): Attic Black-Figure Mastos, Side B, ca 520-500 BCE (Getty Villa)

Ulysses Kay: Aulos (Melanie Valencia, flute; Metropolitan Philharmonic Orchestra; Kevin Scott, cond.)

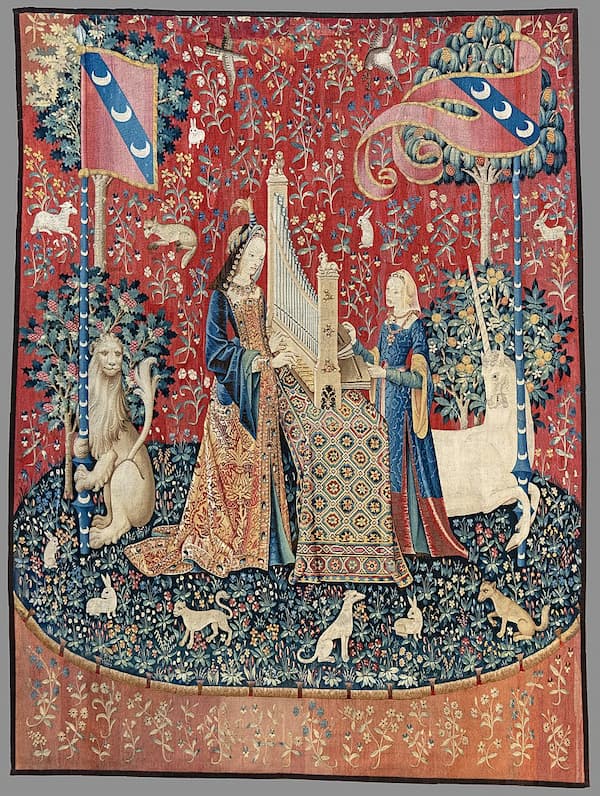

The Comte de Toulouse, Louis-Alexandre de Bourbon, commissioned a set of tapestries for his country residence, located outside Paris. The tapestries, of which 9 survive and 7 are at the Getty, tell The Story of the Emperor of China, but designed to tell the story of an exotic country to which the designer had never been.

In this tapestry, the wife of the Chinese emperor Shun Chi embarks on a pleasure boat. She has three servants to attend her, one of whom plays a little keyboard instrument. On the landing, there are acrobats, dancing monkeys and rate, and two instrumentalists, on playing a double aulos and other a kind of cornett.

Emperor Shun Chi, or Shunzhi, was the Emperor of the Qing Dynasty from 1644-1661 and the first Qing emperor who ruled over China proper. Although there’s an extensive history in China of this emperor and his 4 wives and consorts, what’s represented here are European fantasies of the treasures and pleasures of the east. The work was created after designs by Guy-Louis Vernansal (1648 – 1729), Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer (1636 – 1699), and Jean-Baptiste Belin de Fontenay (1653 – 1715) and was woven at the Beauvais Manufactory.

The little keyboard could be a portative organ but would need someone to provide air for its sound. The other two instruments are known from Western sources.

Tapestry: L’Embarquement de l’impératrice, from L’Histoire de l’empereur de la Chine Series, design about 1690; weave about 1697–1705 (J. Paul Getty Museum)

John Adam: China Gates (Jeroen van Veen, piano)

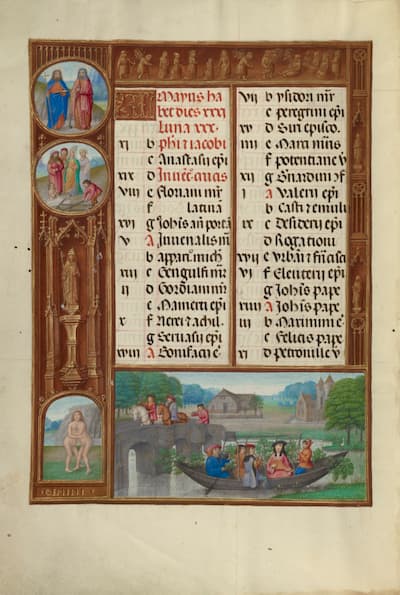

In this page from an early 16th century religious book for the month of May, we have a listing of the saint’s days for the month – including Pope John I, St. Boniface, St. Anastasius and others. The decoration around the side is shown like the interior of a church, with statues with carved surrounds. At the bottom of the page, next to an image labelled Gemini, of a figure with two bodies but only one head, there’s a river scene. As three men cross over a stone bridge, a little boat, hidden behind tree branches, passes under the bridge, holding two woodwind players and a woman playing a lute. The man at the front of the boat appears to be blowing into a bottle (or perhaps drinking from it) while holding an oar and the man at the back of the boat is steering with his oar. The players are dressed in elegant clothes matching those of the men on the bridge.

The combination of lute and recorder was not unusual, as the recorder was often a replacement for the human voice in singing.

Workshop of the Master of James IV of Scotland: May Calendar Page, 1510-1520

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

Ernst Gottlieb Baron: Concerto for Recorder and Lute in D Minor (Gianpaolo Capuzzo, recorder; Pierluigi Polato, lute)

In this lovely chalk drawing, done on off-white paper, the French artists Jacques-André Portail takes up a favourite subject: music making. Here, two women share a song book while a flautist accompanies them. Behind them, a man with one hand in his vest and another in his pocket leans forward to watch and listen. The emphasis is both on the action of making music and the elegant clothes they are wearing. The four subjects are absorbed in the music. Portail’s style here is to draw the shadows, leaving the places where full light would have hit the clothes uncoloured.

Jacques-André Portail: A Music Party, 1738 (J. Paul Getty Museum)

Julie Pinel: Nouveau receuil d’airs sérioux et à boire: Sombres lieux, obscures forêts (Earthly Angels)

This 16th century portrait of a woman with a book of music is a picture of utter wealth and culture. The dress is in a style which was popular in the 1540s and its detailing shows off not only her taste but the painter’s ability. The cutwork design on her dress, the cut sleeves lines with fur, and the elaborate weaving on her belt all attest to her wealth. If we look at the music book, we can see from the clefs that it’s for a man’s voice – this is probably a book for a tenor voice, rather than her soprano or alto voice, but that would be a hidden aspect to most viewers. There are no words in the book, but that may have been for lack of space.

The artist, Francesco d’Ubertino Verdi, was known as Bachaicca (1497-1557) and was a painter at the court of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici in Florence. His colleagues and peers included the important Florentine artists of the time, such as Pontormo, Bronzino, Francesco Salviati, Tribolo, Benvenuto Cellini, Baccio Bandinelli, and his in-law, the sculptor Giovanni Battista del Tasso. His work is known for and even commented upon by Vasari, for his accurate illustrations of bird and here, on the tablecloth, are a grey shrike, a blue jay, a wren, and a yellow hammer. Bachiacca and his brothers were known for their work not only as painters but also as embroiderers and all of that is reflected in this work.

The music, unfortunately, has not yet been identified, but is a normal work for the early 16th century. The cut-C time signature was in use from about 1600 onward and the music shown most runs in stepwise motion, except for the octave leave at the bottom of the first page. By pointing to the first note (after a couple of rests), is the unidentified woman signalling where you (the male viewer) should join.

Bachiacca: Portrait of a Woman with a Book of Music, ca. 1540-1545 (J. Paul Getty Museum)

Bachiacca: Portrait of a Woman with a Book of Music, detail of music, flipped, ca. 1540-1545

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

A painting from about 80 years later by Domenico Fetti, shows another man with music, but this time in a more theatrical setting than the domestic one above. The whole setting is a bit strange – the man, dressed in clothes for acting rather than for regular use, has his feet stuffed into backless shoes, with his socks tumbled down around his ankles. He gestures dramatically toward an overturned bowl, familiar from vanitas paintings as symbolising the emptiness of material possessions. His ear is pierced for an earring and his intense eyes seem to be conveying something to the viewer. In the background, two figures watch with interest. It seems more like a rehearsal scene than the usual capturing of a moment in time. The music, unfortunately, cannot be read, but can be seen to be music.

Domenico Fetti: A Man With a Piece of Music, ca. 1620 (J. Paul Getty Museum)

Antonio Draghi: La lira d’Orfeo: Ma, divertim’io voglio (Julian Prégardien, tenor; Teatro del mondo; Andreas Küppers, cond.)

This image of a lady playing a lute, from the workshop of Bartolomeo Veneto, shows us another partbook. She seems not to be playing from it, as it’s turned towards the viewer. The painting is filled with the artist’s skill: her hair is covered with a sheer veil and her dress and sleeves are decorated with elaborate embroidery and jewels. Her wavy hair comes out clearly. As does the ermine pelt draped across her left arm.

In the 19th century, this painting was thought to have been painted by Leonardo da Vinci, because of all the parallels with his portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, known as Lady with the Ermine (Krakow). However, better knowledge of the works of Bartolomeo Veneto shows this same lady with other objects, such as a wheel, making her Saint Catherine of Alexandra. Bartolomeo worked in Ferrara at the Este court from 1505 to 1508 and by 1520, he was a portraitist in Milan. Where this work shows Leonardo da Vinci’s influence, later works by Veneto show his awareness of Titian’s portraits.

Bartolomeo Veneto and workshop: Lady Playing a Lute, ca. 1530 (J. Paul Getty Museum)

Bartolomeo Veneto: Saint Catherine Crowned, ca. 1520

(Glasgow, Scotland: Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum)

John Bartlett: Sweet Birds Deprive Us Never (Emma Kirkby, soprano; Anthony Rooley, lute)

Let all this exalted musicmaking take us into the idea that music was only for the upper classes, we look to the French artist Georges de La Tour (1593-1652) to show us the other side of music making. In his painting from ca. 1625, he gives us The Musicians’ Brawl. In the center, two musicians fight. The man on the left has a knife in one hand and the crank of his hurdy-gurdy in the other. The man attacking him has a shawm in one hand and in his other, a lemon, to check if his opponent is truly blind. Behind them, two more musicians look on and laugh – one holds a violin and the other a bagpipe. The woman at the back left grasps her broom and looks to the viewer to help stop this fight.

As with many of de La Tour’s paintings, everything is compressed into a shallow space. The details of the worn and tattered clothing and the qualities of the combatant’s skin and hair are all clearly presented. Is the fight over a place to perform or is it on a more personal level? The viewer is placed so close to the action that there’s a danger it will all spill out of the frame and involve the real world.

Georges de la Tour: The Musicians’ Brawl, ca. 1525-1530 (J. Paul Getty Museum)

Anonymous: Hoboken Brawl (The Broadside Band; Jeremy Barlow, cond.)

The Getty collection ranges from Greek vases to modern classics. In this selection, we see music as a mythological symbol, as an indication of wealth and culture, and as an art of the street musician. It’s beauty, it’s culture, it’s entertainment, and it’s a way of making a living.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter