Considered the first and oldest art museum and art school in the United States, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) was founded in 1805. Known for its collections of 19th and 20th century materials, it also has a strength in collection of art by Philadelphia and Pennsylvania artists.

The breadth of music-related works carries us from the early 19th century to the modern day.

The American artist Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) moved into the work of printing and etching and found a place there for decades. Her 24-year-old working association with printer Kenneth Tyler opened the world of lithography (creating art on prepared limestone) and she responded to it in a painterly way. Tyler said Lithography stones are responsive to every gesture. It is possible to create combinations of ethereal washes, crayon lines, and dense brushstrokes. Tones may vary from very delicate washes to fully saturated solids. This is visible in this lithograph from 1995, where it seems more like a watercolour in its handling of colour blending than the stronger lines associated with regular prints. The title, Making Music, leaves us as the viewer in a middle place: are we watching people make music or are we making music ourselves? The centre black lines could be the staves or could be the sound waves. It’s an intriguing picture of the invisible side of music.

Helen Frankenthaler: Making Music, 1995 (PAFA)

Tan Dun: 8 Memories in Watercolor: No. 5. Red Wilderness (Anna Goldsworthy, piano)

In a more traditional image of music making, Romare Bearden used collage technique to create a child’s music lesson. In his 1983 collage dedicated to the jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams, Bearden takes us to a front-room parlour for a music lesson – the music is printed but all the other details are from Bearden’s imagination. Even the piano keys are fanciful, not in the familiar 2 black keys + 3 black keys pattern but even appearing as 4 black keys in one place. There’s a metronome and a vase of flowers on top of the upright piano.

Visually, this print was inspired by two Henri Matisse paintings – “The Piano Lesson” (1916) and “The Music Lesson” (1917), but Bearden turned both of those paintings around so we’re not looking at the student face-on. “The Piano Lesson” also inspired Pittsburgh-native August Wilson’s 1987 play of the same title.

Romare Bearden: The Piano Lesson (Homage to Mary Lou), 1983 (PAFA)

Henri Mattise: The Piano Lesson, 1916 (MOMA)

Henri Matisse: The Music Lesson, 1917 (Barnes Foundation)

Mary Lou Williams: The History of Jazz According to Mary Lou

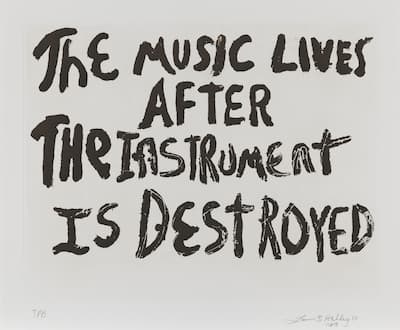

American artist Lonnie Holley (b. 1950) has taken his experience in growing up in America to bring the black experience in America into view. His sculptural creations have taken on the themes of the black churches that were bombed during the civil rights era and on how one’s name and ideas live on after death. Here, Holley makes a statement about legacy, using music as the metaphor: “The Music Lives On After the Instrument is Destroyed.” In the world of Black Lives Matter, this statement has a sobering power. He’s also created an earlier work with this title with a burned electrical guitar and a mutilated saxophone, decorated with flowers and some wire-art in the Picasso tradition.

Lonnie Holley: The Music Lives, 2013 (PAFA)

Holley: The Music Lives After the Instruments Is Destroyed, 1984 (Souls Grown Deep Foundation)

Karol Beffa: Destroy (Karol Beffa, piano; Quatuor Renoir)

Engrossed, the woman in orange leans over the bench back of the seats in front her, her head on her hand, listening intently. Behind her, another woman has fallen asleep and two others just lean back and listen. We’re caught up in her intensity, listening vainly for what has entranced her. From the straight back on the seats and the decorative finial on the end of the seat, she appears to be in a church. The fact that the woman in the row behind her holds a sheet of paper makes it clear that we’re not in a church ceremony but a concert held in the church.

Dephine Bradt: Music, ca. 1919 (PAFA)

Felix Mendelssohn: String Octet in E-Flat Major, Op. 20 – IV. Presto (Kodály Quartet; Auer String Quartet)

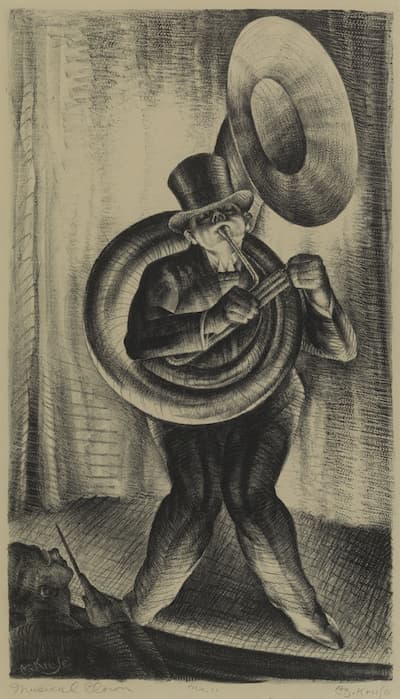

New York artist Alexander Z. Kruse takes us to a music hall to see a Musical Clown. Our poor player is engulfed by his instrument, his top hat is only held up by his nose, and his knees seem to buckle under the weight. He’s concentrating so much on his own misery that he can’t pay attention to the conductor intently watching him from the pit. On the other hand, he’s a clown so everything is exaggerated and the thought of hearing what he may be tootling on his tuba only adds to the humour.

Alexander Z. Kruse: Musical Clown, before 1930 (PAFA)

Rimsky-Korsakov: Flight of the Tuba Bumblebee (Canadian Brass)

In an interesting juxtaposition of lines and curves, the piccolo player poses in front of a set of open doors. But is she? Artist Jack Bookbinder (1911-1990) poses us a question about what we are seeing. If we were facing the piccoloist, then her instrument should be pointing to our left. As she plays, though, she holds her instrument to the right. Where is the artist? Is he behind the piccoloist and painting what she sees in the mirror? This would appear to be the case as we see the open doors behind her curve with the curve of the mirror. The location looks like the under stage of a theatre and she might be warming up before a production. She’s not dressed like she’s performing on stage, but rather being part of the pit orchestra, performing out of sight under the stage.

Jack Bookbinder: Mirrored Music, 1945 (PAFA)

Pablo de Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 (arr. for piccolo and piano) (Peter Verhoyen, piccolo; Stefan De Schepper, piano)

In this picture of a blind boy and his sister who are out on the street in order to make money. She holds his top hat, with its damaged brim, and looks piteously up at any passer-by. Her bonnet strings are untied she has holes in her shoes, and although her brother is in a long coat, she only has a shawl around her shoulders. Her hair has escaped into tendrils. The plaid around his waist may indicate that he’s an Irish musician, where it was a common practice for the blind to be taught music to play for dances and other entertainments. Here, our children are begging on the street, as shown by the front step and railing where they have stopped.

This image by John G. Chapman was made into an etching by Joseph Alexander Adams and was originally printed in The New York Mirror around 1839. It was reprinted in 1838 in The Token, and Atlantic Souvenir, for 1839. The Token was a gift book issued annually between 1828 and 1842. These gift books were lavishly bound and lushly illustrated collections of prose and poetry and intended for Christmas and New Year’s gift. In the early 18th century in American, New Year’s was a gift-giving holiday. An image such as this would be included to remind the reader to be generous to those less fortunate at a difficult time of year.

Joseph Alexander Adams after John Gadsby Chapman: The Blind Musician, ca. 1839 (PAFA)

Turlough Carolan: Mrs. Edwards (Isao Moriyasu, flute; Masako Moriyasu, Irish harp)

We’ve seen other collages made using musical material, such as the little piece of score paper tucked into Romare Bearden’s The Piano Lesson, but here, music is sandwiched between lines and colours. This 1990 work by Robert Motherwell, Untitled (Red Collage with Music and Crayon Lines), uses the black and white solidity of the music to offset the other colours. The solid orange background is layered with a variety of mustard colours and then, over the top of the music comes the black. The crayon lines pull the orange to the foreground again. Why is the music here? Is it how music functions in our lives -positioned somewhere be the full background and the foreground of our attention? It’s classical music in the collage, but Motherwell has obscured the elements that would let us readily identify the works. We must imagine what classical composer he’s hiding from us here.

Robert Motherwell: Untitled (Red Collage with Music and Crayon Lines), 1990 (PAFA)

Friedrich Kuhlau: Piano Sonatina in C Major, Op. 20, No. 1: II. Andante (Jens Lühr, piano)

In this tour around the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, we’ve seen music used to stir the public empathy for the less fortunate, musical images that honour the learning of music, and those that show how audiences can get caught up in music. The abstract expressionists use music or musical titles to help us think about the role of music, and Holly confronts us with the idea that even when the vehicle, musical instrument, are destroyed, music will live on. Music as social and political statements show how central music is to our lives.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter