Clara Schumann

To prove his potential earnings from composition to his highly skeptical father-in-law —we all remember that Friedrich Wieck had taken Robert to court in order to prevent the “old alcoholic” from marrying his daughter Clara — Robert Schumann composed well over hundred songs in the first half of 1840. During this period “Lieder” fell almost exclusively in the domain of the home, where talented amateurs performed them. Because of this great demand, publishers bought a good many of Schumann’s Lieder during 1840, and for this reason — among many others — the court would eventually approve Schumann’s petition to marry Clara in September of the same year.

Having gotten his girl, Schumann turned his attention towards proving to the professional musical community at large that he was a serious composer. As such — and clearly designed to escape the shadow of Beethoven — he almost exclusively devoted all his compositional energies to the symphonic genre in 1841.

By 1842, his attention had turned towards chamber music. Entries in his household books — daily diaries in which the composer recorded highly personal as well as professional information — reveal, that Schumann began a detailed study of the quartets by Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven between April and June of 1842. The practical outcome of his theoretical studies manifested itself in a Piano Trio, which would eventually become the Fantasiestücke (Phantasy Pieces) Op. 88, the Piano Quartet Op. 47, three String Quartets Op. 41, and the Piano Quintet Op. 44.

Completed in a matter of weeks and dedicated to his wife Clara, the Piano Quintet virtually invents a brand new musical genre by adding the new piano to the string quartet of old. This combination was only made possible by the significant advances in the design of the piano, as modern instruments allowed for dramatically increased power and dynamic range. Schumann takes full advantage of both forces in combination, “alternating conversational passages between the five instruments with concertante passages in which the combined forces of the strings are massed against the piano.”

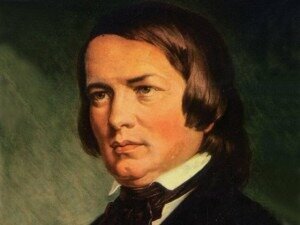

Robert Schumann

Musically, the quintet synthesized Schumann’s eloquent pianist style with the melodic mastery gained in 1840 and the symphonic approach to texture acquired in 1841. Early critics almost unanimously praised the composition. It was noted, “the work nicely blends both poetic and purely musical elements in a marriage between both Schumann’s musical and literary ambitions, and between the popular drawing-room chamber music aesthetic and the concert-hall symphony.”

The only contemporary critic to condemn the composition was Franz Liszt, who called it “zu Leipzigerisch,“ a rather derogatory statement referring to the old-fashioned nature and rather provincial stature of the city of Leipzig. This of course also included Schumann, who was living in Leipzig at that time, and his music. It is hardly surprising that Clara Schumann, who premiered the work in October 1842 with the Gewandhaus Quartet never talked to Franz Liszt again.

The piano quintet will be performed at the Schumann Fest.

Official Website