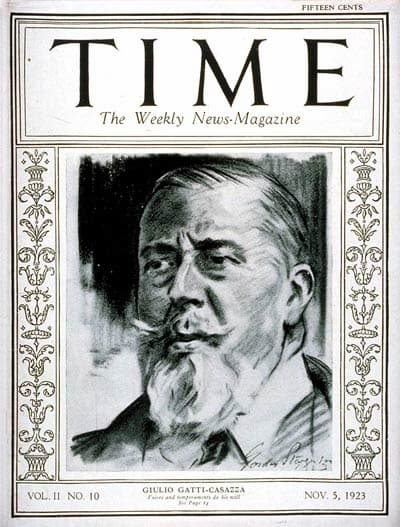

He single-handedly revolutionized the world of opera by applying an unprecedented entrepreneurial philosophy to arts management. Giulio Gatti-Casazza managed La Scala in Milan for a decade, and he also served as the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera of New York for a record 27 seasons! His ideas of organizing opera houses as not-for-profit cultural companies situated an ancient art form decidedly in the modern world.

Giulio Gatti-Casazza

“Even the greatest genius,” he writes, “would not be able to change the nature of things and prevent the theater from being a great public service; its two faces, artistic and economic, must be wisely harmonized, to ensure the survival of an organism that is so schematic, but not less alive.” Gatti-Casazza was born in Udine but spent his formative years in Ferrara. He studied naval engineering, but his love of opera compelled him to take on the role of general manager at the Teatro Comunale in Ferrara. His way of combining knowledge of opera, his love for music and his gift for management soon attracted attention elsewhere.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Love Duet”

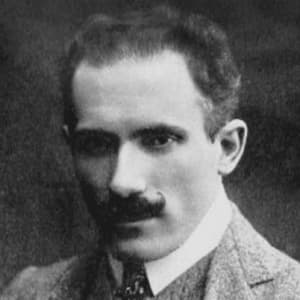

At the recommendation of Arrigo Boito, Gatti-Casazza became the general manager of La Scala, and he oversaw the premiere of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. And as you might know, he brought with him a 29-year old gifted conductor from Parma by the name of Arturo Toscanini!

Arturo Toscanini

He approached his appointment with an almost maniacal passion for organization. Guided by instinct, curiosity and a clear project vision, he made radical changes in Milan. He turned the opera house into a not-for-profit institution dedicated entirely to lyric art. In addition, his vision and unshakable faith in the power of Art meant that the repertoire at La Scala was no longer confined to native composers but reflected wider European operatic expressions. His approach quickly raised eyebrows in Paris and Vienna, and came to the attention of Otto Kahn, chairman of the Met board. He strongly believed that the company needed a robust and creative leader for the future.

Giacomo Puccini: Il Trittico, “Gianni Schicci-O mio babino caro”

Gatti-Casazza arrived in New York in 1908 and brought Toscanini with him. Toscanini became the guiding artistic presence—at least until 1915—and Gatti-Casazza engaged the most important singers of the day, starting with the young Enrico Caruso and Geraldine Farrar. He brought Puccini to New York to oversee a production of Madama Butterfly as well as commissioning La Fanciulla del West and Il Trittico. Listening to Verdi’s advice, Gatti-Casazza made it his vision to have a full house every night, and Toscanini made it a priority to elevate the Met orchestra and chorus into great virtuoso artists. But what is more, Gatti-Casazza was eager to adopt new technologies and made audio recordings of the Met’s leading singers. He also initiated live radio broadcasts of opera from the Met stage, creating the template that still informs the Met transmissions on satellite radio and HD broadcasts in cinemas worldwide.

Engelbert Humperdinck: Hansel and Gretel, “The Witch’s Ride”

In a number of short years, Gatti-Casazza had turned opera into a cultural product in the corporate sense. High-quality productions combined with a self-sufficient business model raise funds without a single dollar of public subsidy. His brilliant insights into the needs of the business helped him to overcome a number of severe predicaments. Toscanini resigned and returned to Italy in 1915, and WWI prevented many European singers from coming to New York.

Giacomo Puccini with Giulio Gatti-Casazza, David Belasco

and Arturo Toscanini in New York

Responding to that need, Gatti-Casazza spearheaded the development of American talent. Under Gatti-Casazza’s leadership, the Met even survived the stock market crash of 1929 and the prolonged depression. He looked at every crisis not as a danger but as an opportunity. Although he never fully mastered the English language, he insisted that operas be done in their original languages if possible. Gatti-Casazza left New York in 1935, but only after having introduced his last great discovery, the soprano Kirsten Flagstad.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter