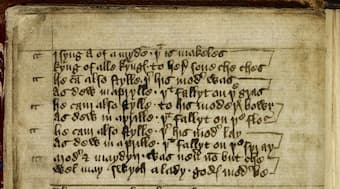

The single surviving source for the poem (ca. 1400) (British Library)

The fifteenth century poem ‘I syng of a mayden,’ also known ‘As Dew in Aprille,’ celebrates the Annunciation and coming birth of Christ. Although thought to be well-known in the 15th century, the poem comes to us now only in one manuscript held in the British Library. It has no music, probably because the music was so well known that it wasn’t necessary to write it out in the 15th century. Analysts say the lyrics lend themselves to song and so composers have set this. We note as well, the opening: I sing of a maiden.

The lyrics start (in a modernized setting): I sing of a maiden | That is matchless. This kind of beginning can be traced back to epic poetry such as Homer’s Iliad, which begins Sing, goddess, of Achillles’ wrath… For the middle verses (2-4), the narrator speaks about the new-born child – he came … as dew in April…. And this is where the alternative title for the song ‘As Dew in April’ comes from. The poem closes with a declaration about the Virgin Mary: Mother and maiden | There was never, ever one but she; | Well may such a lady |God’s mother be.

Composers have seized on this text in the modern day to set it in a variety of ways. With the publication of several books of medieval poetry in the early 20th century, composers could choose long-forgotten poetry for their settings. One such source was Early English Lyrics, an anthology published in 1907 that had been compiled by E. K. Chambers and Frank Sidgwick and that included this poem. Another was A Medieval Anthology by Mary Segar, published in 1915.

In his 4 songs, Op. 35, no. 3, of 1916 to 1917, Holst used A Medieval Anthology as his source.

Gustav Holst: 4 Songs, Op. 35 – No. 3. I sing of a maiden (Susan Gritton, soprano; Louisa Fuller, violin)

Peter Warlock’s setting of 1918 used the Early English Lyrics as his source, setting 18 other poems from that book in addition to this one.

Peter Warlock: As Dew in Aprylle (The Carice Singers; George Parris, cond.)

Arnold Bax’ setting in 1923 brought with it some interesting key and chord changes, indicating that he was starting to look at this text as something more than a medieval work.

Arnold Bax: I Sing of a Maiden (King’s College Choir, Cambridge; Stephen Cleobury, cond.)

A very clear setting is by Roger Quilter, done in 1924.

Roger Quilter: 6 Songs, Op. 25 – No. 3. An old carol (Anthony Rolfe-Johnson, tenor; Graham Johnson, piano)

Patrick Hadley’s setting is one of the two church anthems for which he is best known. This 1936 setting adds on a long introductory section.

Patrick Hadley: I Sing of a Maiden (Winchester Cathedral Choristers; Winchester College Quiristers; Stephen Farr, cond.)

Lennox Berkeley’s 1966 version takes a very slow deliberate style.

Lennox Berkeley: I Sing of a Maiden (King’s College Choir, Cambridge; Peter Stevens, organ; Stephen Cleobury, cond.)

For choristers, one of the best-known setting was that done by Benjamin Britten for his cantata, A Ceremony of Carols, op. 28, written in 1942. It was composed during WWII as he returned by sea from the US. As with other sections of the cantata, Britten uses echo effects and dynamics to make a simple but effective setting for children’s choir.

Benjamin Britten: A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28 – As dew in Aprille (Winchester College Quiristers; Katie Salomon, harp; Malcolm Archer, cond.)

In this setting, the arranger adapted the medieval carol ‘Ecce quod natura’ to the words of the poem to create a sound that is closer to the medieval original than to today.

Anonymous: I Syng of a Mayden (arr. W. Lyons for vocal ensemble) (Voice Trio; Dufay Collective; William Lyons, cond.)

When medieval meets minimalism, we have John Adams’ setting of the text in his opera-oratorio El Niño (2000).

John Adams: El Nino – Part I: I Sing of a Maiden (London Voices; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Kent Nagano, cond.)

This significant Marian text, praising the Virgin Mary, has touched composers of all styles of music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter