Initially, an entire population loved her, yet in the end, that love turned to hatred, and she lost her head in the French Revolution. Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) embodied everything that was rotten with royalty, and she certainly got some very bad press. Yet, behind this façade of pomp, vanity, and pretty diamonds stood a lonely, passionate and art-loving woman.

Queen Marie Antoinette playing the harp

Like a character in a story, music was always present in her life. She was a great patron of music, tirelessly promoting the operas of Christoph Willibald Gluck and staging countless theatrical and chamber music events at court. Marie Antoinette loved dance and she loved music, and it wasn’t unusual for her to participate in performances. Apparently, she was singing French songs at the age of 3, and she personally met the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart during his first concert at Castle Schönbrunn in 1762. According to contemporary witnesses, “she sight-read music at a professional level, and she was a dancer par excellence.” She received music lessons from Gluck, Wagenseil, Joseph Stephen, and Johann Adolph Hasse. In addition, she personally appeared as a shepherdess in “Il Trionfo d’Amore,” a ballet given in honour of her brother Archduke Joseph’s wedding. And when Marie-Antoinette, aged 14 married the future King of France age 15, Jean-Baptiste Lully’s opera Persée sounded in the newly completed Royal Opera house.

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Persée (Mathias Vidal, tenor; Hélène Guilmette, soprano; Katherine Watson, soprano; Tassis Christoyannis, baritone; Jean Teitgen, bass; Marie Lenormand, mezzo-soprano; Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Marie Kalinine, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Dolié, baritone; Zachary Wilder, tenor; Concert Spirituel Chorus; Concert Spirituel Orchestra; Hervé Niquet, cond.)

Marie Antoinette in a red hunting attire, 1772

The wedding celebrations, which included the “ritual bedding,” continued for several weeks until a firework on the Place de la Concorde killed 132 people, a rather grim omen for a reign that was to come to a tragic end. During the twenty years of her influence and reign, Marie Antoinette had a profound impact on the French musical landscape. Although she naively did not associate music with politics, her sincerity and enthusiasm, eclectic taste and sure judgment “did more for art than all the politic-artistic strategies of more enlightened princes.” She favoured composers from central Europe, and Christoph Willibald Gluck owed much of his success to her. Under her patronage, Gluck became the master of French opera and, with royal backing wrote a series of works that had a lasting impact on the musical theatre by “reforming the foundations of the French style.” Marie Antoinette did indeed enjoy the mythological and heroic subjects treated by Gluck, but she was particularly fond of the simple and frequently naïve style of opéra comique, with André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry in particular enjoying her favours. Grétry was appointed her harpsichord teacher and personal director of music to the queen, and his works premiered with regularity on the royal stages of Versailles.

André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry: L’épreuve villageoise (Sophie Junker, soprano; Talise Trevigne, soprano; Thomas Dolié, baritone; Francisco Fernández-Rueda, tenor; Opera Lafayette Chorus; Opera Lafayette Orchestra; Ryan Brown, cond.)

Marie Antoinette’s harp

Marie Antoinette’s favourite musical instrument was simultaneously the most popular instrument of the day. The harp had started to replace the harpsichord in the salons of the upper bourgeoisie. The Queen received instructions from Joseph Hinner, and it has been said that because of her interest, “the harp experienced a golden age in France, as it had become the must-play instrument for French demoiselles.” As a contemporary wrote, “The harp today is the instrument of fashion; all our ladies are passionate to play it… it allows them to show off their pretty hands, the nimbleness of their fingers and even their dainty little feet and ankles.” Marie Antoinette played the harp every day, and she had several beautifully decorated instruments at her disposal. She also encouraged composers to write music for it. In fact, a number of rising stars flocked to Paris looking for her patronage, and that included Jean-Baptiste Krumpholtz, Scarlatti, Mozart, Johann David Hermann, Johann Baptist Hockbrucker, C.P.E Bach, and Antonio Rosetti; all of whom contributed to the classical harp repertoire. It is probably less well-known that Marie Antoinette also composed her own tunes and melodies.

Jean-Baptiste Krumpholtz: Harp Sonata in F Major, Op. 15, No. 2 (Sandrine Chatron, harp; Stéphanie Paulet, violin)

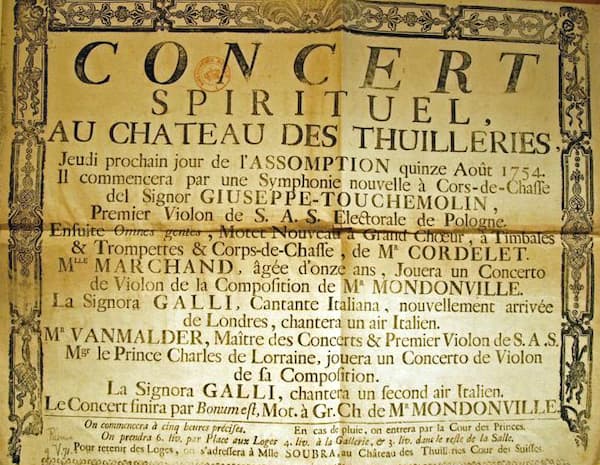

Concert Spirituel poster

Salon music aside, Marie Antoinette took great interest in public concerts, especially performances at the Concert Spirituel. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was already personally known to the Queen, embarked on a renewed journey to Paris in 1778 in hopes of finding royal patronage. He really didn’t have much luck, as Marie Antoinette was pregnant. Mozart’s mother took a strong interest in such royal news, but the Queen was obviously indisposed. Mozart did not get an appointment, and furthermore, his mother sadly died on that disastrous journey. Joseph Haydn had much better luck, as a number of symphonies were commissioned by a group of freemasons from the Loge Olympique. Every the craftsman, Haydn incorporated a number of French characteristics into his “Parisian Symphonies,” and No. 85 became Marie Antoinette’s favourite. She did, in fact, lend her name to this symphony, and we know that she had genuine affection for it. It is reported that the harpsichord in her prison held the score of this Haydn symphony. “Time has changed,” she is supposed to have said. Well, at least that’s the story.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 85 “La Reine de France” (London Chamber Orchestra; Rosemary Furniss, cond.)

Marie Antoinette’s execution

Marie Antoinette did enjoy her lavish courtly lifestyle, but there was much more to her personality than etiquette, idleness, frivolity and intrigues. In the end, she was simply the lightning rod for French dissatisfaction. She was accused of promiscuity, having affairs with the Marquis de Lafayette and the well-known lesbian English Baroness Lady Sophie Farrell of Bournemouth. She was also accused of staging orgies at Versailles and sexually assaulting her own son. None of it was true, but facts then, as now, are a rather flexible concept. Her story continues to inspire, and a recent production by Thierry Malandain and his Biarritz troupe pays some tribute to her taste for the arts, theatre, music and dance. Fittingly danced to the music of Haydn and Gluck, we are rightfully inspired to look beyond the cliché of a prancing and pleasure-seeking queen.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter