The dashing American bad boy of music George Antheil (1900-1959) was a child prodigy. He dropped out of school and left for Europe. In no time he rubbed shoulders with Ezra Pound and James Joyce, made friends with Gertrude Stein and Leopold Stokowski, and was looking to upstage Igor Stravinsky.

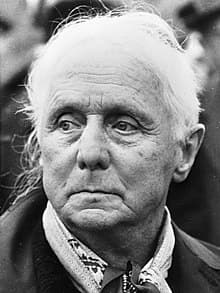

Max Ernst, 1968

He was the first American to write an opera premiered at a major European house, wrote movie music, and a book or two on glandular criminology. Antheil didn’t go to Paris to blend in, he went there to outrage, shock, and offend. He manipulated the press and supposedly kept a loaded revolver on the piano while playing recitals in order to discourage audience protest.

George Antheil, 1927

His groundbreaking Ballet Mécanique of 1924 caused uproar at its Paris premiere. It was written to include the synchronization of 16 player pianos, and when it was first performed in the US the music critic Deems Taylor wrote, “the piece began before a silent and attentive audience. After five minutes of it, a few began to fidget; after six minutes a few more began to cough; after seven a few more began to giggle. At the eighth minute precisely, a man in the third row raised his cane, to which he had tied his handkerchief. At the sight of that white flag the entire house simultaneously gave up trying not to laugh. I don’t know how the piece ends. I am not even prepared to discuss its possible musical value; but I do know that as a comedy hit it was one of the biggest successes that ever played Carnegie Hall.”

George Antheil: La femme 100 têtes (Benedikt Koehlen, piano)

Max Ernst: The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child before Three Witnesses: Andre Breton, Paul Eluard, and the Painter, 1926

In the early 1930s, Antheil encountered many aesthetic currents in experimental art, including absurd miniature Dada theatre, sound poetry pieces, surrealist and futurist expressions. Antheil was a frequent customer at the bookshops of Adrienne Monnier and Sylvia Beach, who carried experimental French writers and English language modernists, respectively.

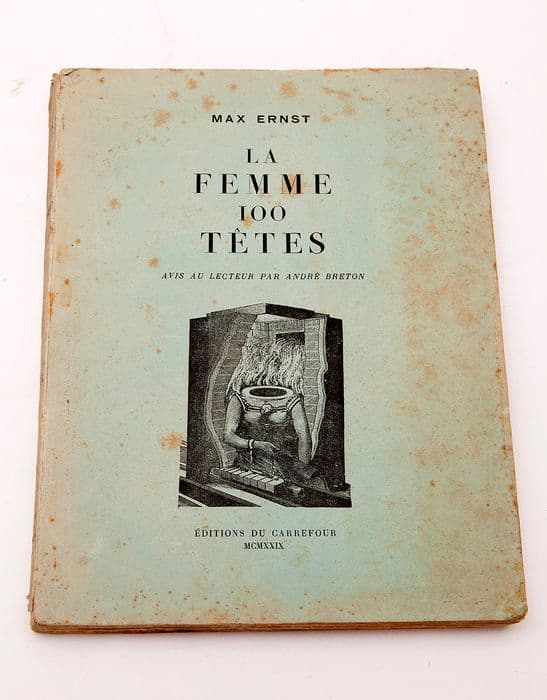

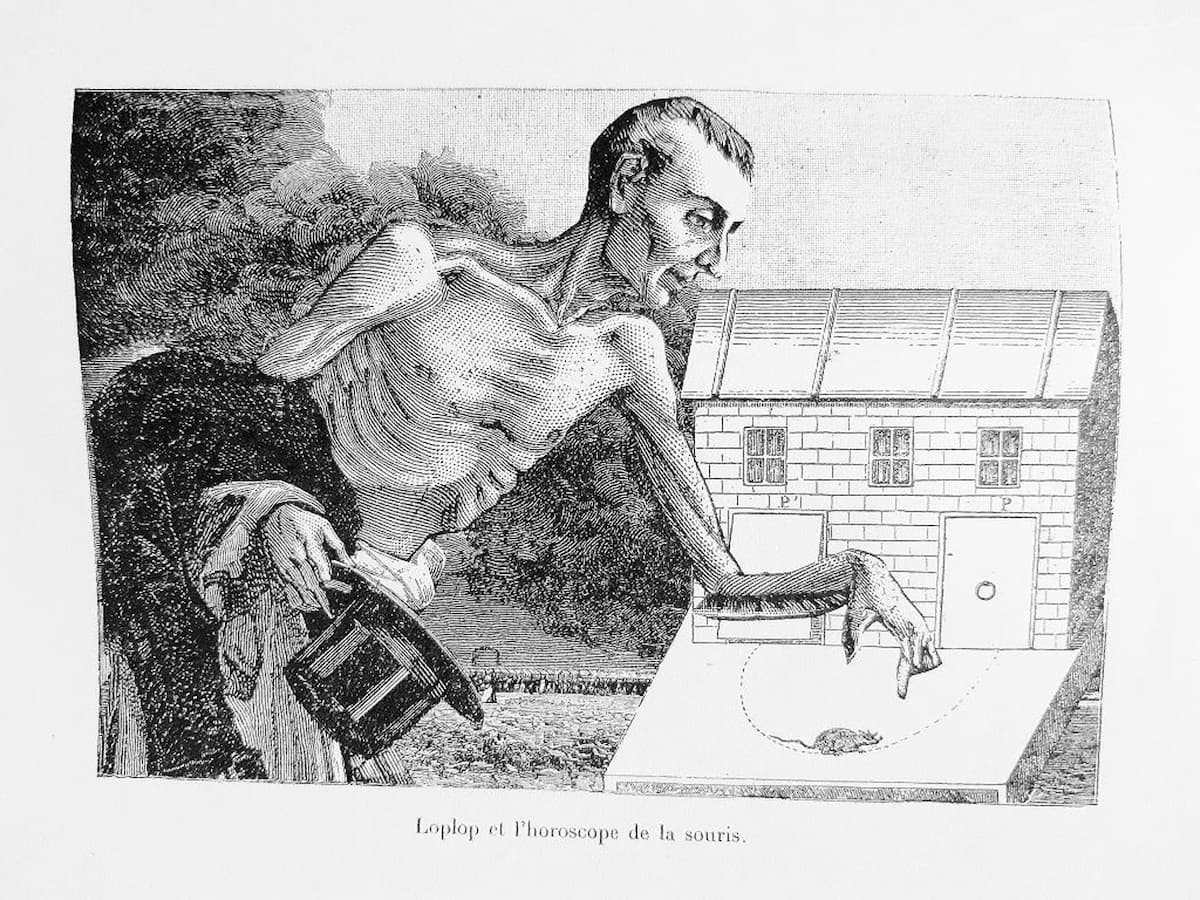

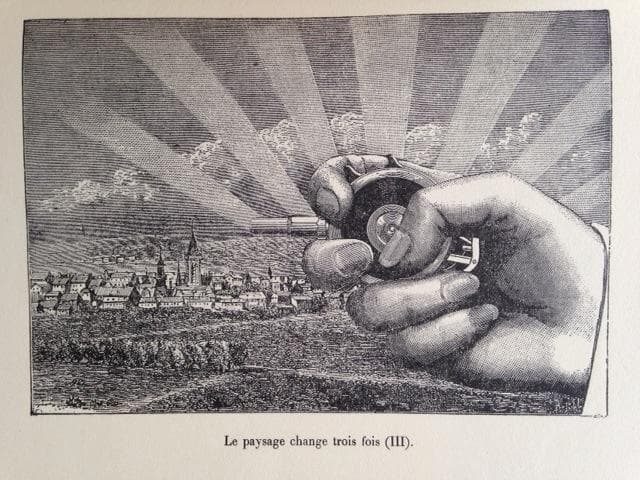

Max Ernst: La femme 100 têtes

It has been suggested that Antheil purchased copy number 657 of 1000 of the first edition of Max Ernst’s La femme 100 têtes at Monnier’s shop. Published in 1929 it carried an introduction by André Breton, and “George’s copy is carefully inscribed in the hand of the composer, George Antheil—not to be borrowed.” Max Ernst (1891-1976) was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and of surrealism. He was essentially self-taught and used a variety of mediums, “paintings, collage, printmaking, sculpture, and various unconventional drawing methods—to give visual form to both personal memory and collective myth.”

George Antheil – La Femme 100 Têtes – 3 Preludes

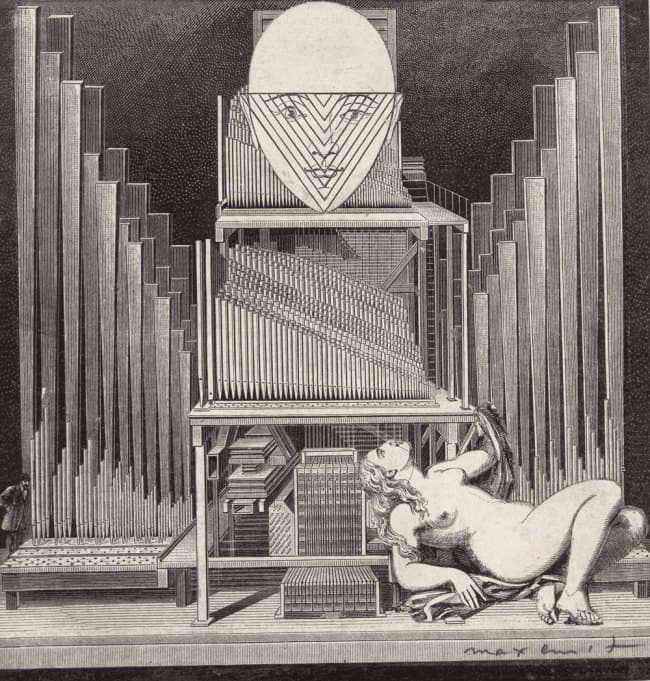

Surrealism was an artistic and literary movement in Paris in the 1920s that prized the irrational and the unconscious over order and reason. Ernst was a key contributor to this movement and he invented the frottage technique. “It places paper over a textured material, such as wood grain or metal mesh, and rubbing it with a pencil or crayon to achieve various effects.” Having little control over the resulting patterns, Ernst delighted that “he came to assist as spectator at the birth of all my works.” Eventually he translated the method from paper to painting, “using the word grattage to describe this technique of scraping wet paint off the canvas to achieve similar patterned effects.” Ernst described the fragmented logic of collage as “the culture of systematic displacement.”

Max Ernst: La femme 100 têtes

In the highly ambiguously worded collection La femme 100 têtes Ernst presents 146 collages in nine groups or chapters with thematic imagery in each of the nine. Ernst had collected etchings from nineteenth-century storybooks, and combined them into curious collages with eerie captions and hauntingly suggestive overtones. “The narrative thread is healthily disjunct, and the reader is lead further into Ernst’s liberated world where everything is possible.”

Max Ernst: La femme 100 têtes

Antheil composed the corresponding music at the French Riviera near Nice in the winter of 1932-33. He referred to these preludes as “short, terse and steely, representing the subconscious and strange feeling of my childhood in New Jersey.” Antheil noted that he intended to compose 100 preludes for the Ernst book, but in the end he left us a set of 45 short pieces.

Prelude IX (“Sad”) from La Femme 100 Têtes (Antheil)

When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, it ended the flourishing era of “American expatriate artists living the good bohemian life abroad in France.” Antheil returned to the United States, and La Femme “marks the end of a decade of experimentation and initiation for young Antheil and the beginning of a period of reassessment.”

Max Ernst: La femme 100 têtes

The work premiered at the Second Yaddo Festival of Contemporary Music in Saratoga Springs, New York, on 20 September 1933. Each of the preludes is numbered with a Roman number, and the set concludes with “Percussion Dance.” Antheil was a prodigious pianist, and this unusual set of visionary etudes directly inspired by Ernst’s collage taps the essence of surrealist thought and expression.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter