Who was Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved, the woman who inspired a passionate, unsent love letter written in the summer of 1812?

Her identity is a question that has preoccupied historians and music lovers for generations.

Beethoven in 1803

One of the most likely candidates is a student and friend of Beethoven’s named Josephine von Brunsvik.

But regardless of whether Josephine was or wasn’t the Immortal Beloved, Beethoven was in love with her. She was also a talented pianist who performed his music. She’s an important and fascinating figure in her own right.

Josephine von Brunsvik’s Early Days

Josephine von Brunsvik was born on 28 March 1779 in present-day Bratislava, Slovakia. She was the third of four children: one boy and three girls.

The Brunsviks grew up in a palace near Budapest and enjoyed the advantages of a rigorous education from private tutors.

Part of their education was musical. Josephine’s brother, Franz, became an accomplished cellist, while the three girls studied keyboard.

Tragedy – And Meeting Beethoven

Josephine von Brunsvik

In 1792, their father died, leaving their mother Anna a widow.

After their father’s death, it became vitally important for the daughters to make socially and economically advantageous marriages, since they no longer had their father’s income to rely on to support them.

In 1799, Anna brought two of her daughters, twenty-year-old Josephine and twenty-four-year-old Therese, to Vienna to take some piano lessons from an up-and-coming teacher named Ludwig van Beethoven. Anna had been a fan of Beethoven’s compositions for several years.

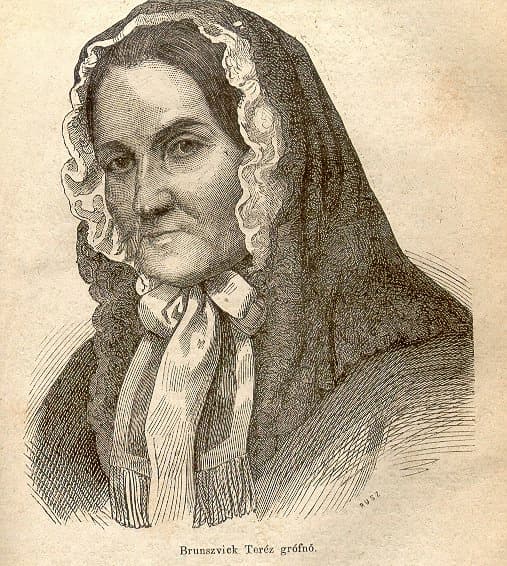

Therese Brunsvik

Therese wrote in her memoirs about their meeting:

Like a schoolgirl, with Beethoven’s Sonatas for Violin and Violincello and Pianoforte under my arm, we entered.

The immortal, dear Louis van Beethoven was very friendly and as polite as he could be.

After a few phrases de part et d’autre, he sat me down at his pianoforte, which was out of tune, and I began at once to sing the violin and the ‘cello parts and played right well.

This delighted him so much that he promised to come every day to [our hotel].

For a little over two weeks, the 29-year-old Beethoven gave daily lessons to the Brunsvik daughters. He befriended both of them and socialised with them after their lessons.

Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 3

Meeting Her Future Husband

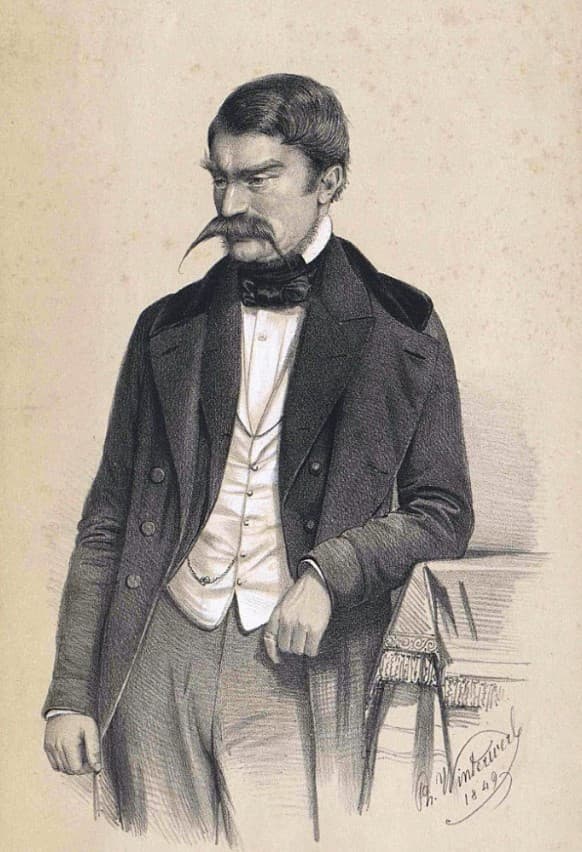

Joseph Deym

Toward the end of their Vienna trip, the sisters visited a gallery owned by a man named Count Joseph Deym.

As soon as Deym saw Josephine, he decided that he wanted to marry her. He proposed to her, and she accepted. He was forty-seven, and Josephine was twenty.

Her mother thought Deym was wealthy and socially well-connected. Unfortunately, it turned out he was not.

Although Josephine was later bitter about the pressure that her mother put on her to marry Deym, she also gradually grew warmer toward him over time.

Continuing Her Studies with Beethoven

Her sudden marriage did not preclude Beethoven from continuing to visit her. He even gave her free piano lessons after her marriage.

Josephine was no dilettante when it came to music. At a December 1800 house concert, she performed the piano part to Beethoven’s third violin sonata, with the virtuoso violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh on violin.

For years to come, Beethoven’s music would be performed in the Brunsvik and Deym social circles; all of Beethoven’s violin sonatas except the last were played in Josephine’s home.

Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 12 No. 3

Becoming a Young Widow

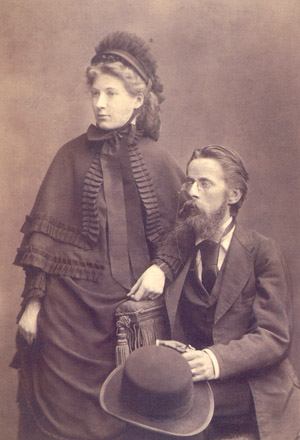

Josephine von Brunsvik before 1804

Disaster struck the household in January 1804 when Count Deym came down with pneumonia and died. He left behind a pregnant 24-year-old wife and three small children.

Beethoven continued his friendship with Josephine even after she’d been widowed, performing in her home and giving her lessons. Their emotional connection became stronger than ever.

A year after Deym died, Josephine and Therese’s sister, Charlotte, noted:

Our little music events have started again… Pepi [Josephine] played the piano superbly; I’m lacking the courage so far to let myself being heard. Beethoven is very often here, he gives Pepi lessons – this is a bit dangerous, I must confess.

Why Was the Beethoven Affair So Scandalous?

Things were getting “dangerous” because the two were falling in love. They even exchanged love letters, verbalising their feelings.

However, being open about their romance to the broader world or even getting married was simply not an option, given their difference in class.

It’s important to remember that Josephine couldn’t just worry about herself here. She also had the social and economic standing of her young children to worry about. Their prospects would be ruined if Beethoven were to become their stepfather. Worse, she almost certainly would have lost custody of them.

She believed she had to sacrifice her happiness in order to be a good mother. She once wrote:

Every woman who becomes a mother is heading a new creation of a rejuvenated humankind – whose nature she has to preserve, whose strengths she has to develop … Her position puts her as the sanctuary of humanity … such she must be able to sacrifice her well – being for that of her children a thousand times.

For his part, in 1805, Beethoven wrote the tender song “An die Hoffnung” (“To Hope”), op. 32, and dedicated it to Josephine.

Beethoven: An die Hoffnung, Op. 32

Breaking Up With Beethoven

Nevertheless, Beethoven and Josephine’s relationship lasted from 1804 to 1807. Josephine tried to encourage a platonic bond, but the limit pained Beethoven.

In late 1807, she listened to the warnings of her well-meaning family and pulled away from him, despite the fact that her feelings for him were still very much present.

In response, he removed her name from the dedication of “An die Hoffnung.”

In 1808, she and her sister Therese departed for Switzerland and Italy with her sons. She wanted the trip to be an educational one, similar to how her mother had once set off for Vienna with her and Therese in tow.

Meeting Her Villainous Second Husband

Christoph von Stackelberg

On the trip, she met an Estonian baron named Christoph von Stackelberg. He was a well-educated cad, and during their journey, he began tutoring the boys while also regaling their mother with stories.

He joined the Brunsviks when they returned home to Vienna. Josephine later claimed she never loved him, but in Geneva, he managed to seduce her. She had a daughter by him in December 1809.

He kept pressuring her to get married, and he eventually gave her an ultimatum: he would no longer teach her sons unless she became his wife. She gave in.

Nine months after their February wedding, she gave birth to another child, this time a son.

The Relationship With Stackelberg Deteriorates

Predictably, their marriage started deteriorating as soon as it began. By the summer of 1810, the relationship was in dire straits.

By modern measures, Stackelberg was abusive. He dictated that the children’s hands be tied together if they touched anything, and that they be tied to their beds if they played on the floor.

In 1811, Josephine had had enough of him, and she gave up on the physical side of their relationship.

Once the couple started having money troubles on top of everything else, it became clear that the relationship couldn’t be saved.

In 1812, she put her foot down to keep Stackelberg from spending the remaining money that she wanted to save for her children. They parted ways.

Meeting Beethoven Again

While attempting to arrange financial matters, she found herself traveling to Prague in the summer of 1812. Beethoven also traveled there that summer.

In the town of Teplice, he wrote a passionate, unsent love letter to a woman whom he only referred to as the “Immortal Beloved.” It was dated 6 or 7 July.

A few months later, Josephine discovered that she was pregnant. She hadn’t been with Stackelberg, and some historians have theorized that the baby’s father could have been Beethoven.

Her daughter Minona was born in April 1813, nine months after the Immortal Beloved letter was written.

Learn more about Beethoven and Minona.

Beethoven: Violin Sonata No.10 Op.96

Beethoven’s tenth violin sonata, written in late 1812, a few months after writing his Immortal Beloved

The Return of Stackelberg

After the birth, she made ends meet by running Deym’s gallery and letting out rooms in the family home.

She also began a relationship with another tutor of her children. In early 1814, she got pregnant by him.

In 1814, Stackelberg returned to Vienna and attempted to bring Josephine and the children to his home in Estonia. Apparently, he had just inherited some estates, and he wanted his family with him. A pregnant Josephine resisted.

The following day, the police came and abducted the youngest children. Stackelberg claimed that molestation had occurred between the Deym children and the Stackelberg children.

To add insult to injury, Stackelberg eventually became unwilling to care for the children and left them with a deacon in Bohemia. It was late 1816 when Josephine and Therese received word of their whereabouts, but just as soon as they scrounged up the money to pay for their travels, Stackelberg’s brother spirited them away.

Josephine gave birth to her final child, Emilie, in September 1814. The tutor left the household and took the baby with him. Little Emilie would die of the measles as a toddler.

Josephine’s Tragic Final Years

Josephine was nearing the end of her life in unimaginably nightmarish circumstances.

Her youngest daughter was dead. She had no idea where the three next-youngest children were. And the eldest from the marriage with Deym were teenagers and drifting away from their mother.

Unsurprisingly, under these circumstances, Josephine’s mental and physical health deteriorated.

In 1819, understanding that Josephine was near death, Stackelberg returned to Vienna from Estonia with the children that he had taken from her.

In the end, she let them go back to Estonia with him because she knew she was too weak to continue raising them.

She stayed in her home more and more and didn’t see friends. Although she and Beethoven had been in touch intermittently for years, by the end of her life, they weren’t speaking, either. That said, there is obviously much that we don’t and can’t know about their relationship. So who knows what exactly sparked the end of their relationship?

Josephine died in March 1821 of tuberculosis. She was forty-two years old.

The year before, Therese had written of her sister: “Her fate was extremely tragic.” It was one of the great understatements of classical music history.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter