On 15 January 1622, one of the greatest writers in the French language was baptized in Paris. His name was Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, but everybody immediately recognizes him by his stage name Molière. It is thought that Molière adopted his stage name in homage to the novelist François de Molière d’Essertines, a notorious libertine, who was assassinated in 1624. However, it has recently been proposed that he might also have had the lutenist, dancer, and composer Louis de Mollier (1615-1688) in mind when choosing his stage moniker.

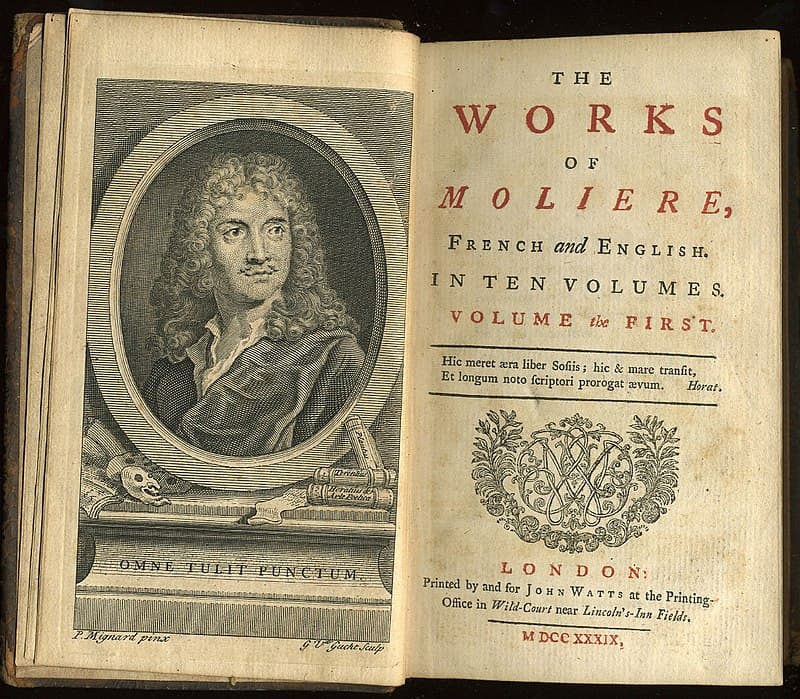

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (Molière) by Pierre Mignard

Molière was one of the greatest comic geniuses the world has ever seen, and he is certainly the master of social comedy. In his plays he singlehandedly analyzed various aspects of contemporary society, “penetrating into the essential characteristic of people.” He founded the troupe known as the “Illustre Théâtre” and toured the French provinces, writing plays and acting in them.

Louis XIV of France

Molière managed to establish a permanent theatre in Paris under the patronage of Louis XIV, and his plays “compose a portrait of all levels of 17th-century French society and are marked by their good-humored and intelligent mockery of human vices, vanities, and follies.” The 19th-century French writer Stendhal rightfully called Molière “the great painter of man as he is.”

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Monsieur de Pourceaugnac (excerpt) (Jerome Correas, harpsichord; Les Paladins; Jerome Correas, cond.)

Molière counted a number of musicians among his forebears, including his violinist uncle Michel Mazuel, who was appointed by Louis XIV as a “compositeur de la musique des vingt-quatre violons” in 1654. While he was known as an actor and singer, Molière did surround himself with well-known musical personalities, including the lute player Charles Dassoucy (1605-1679), and the violinist and dancing master Paul de La Pierre (1612-1689). However, his single-most important musical collaborator was no doubt Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687).

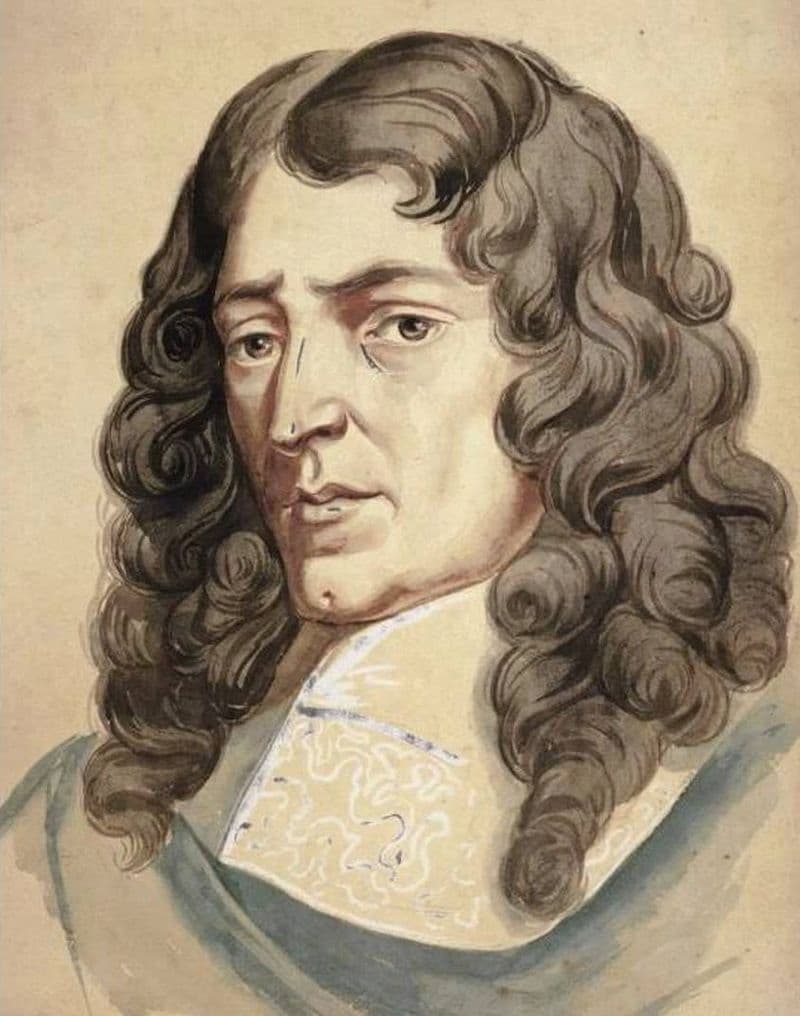

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Lully by Paul Mignard

“Starting with the single contribution for the comédie Les Fâcheux put on at the chateau of Vaux-le-Vicomte on 17 August 1661, and ending with Psyché, a tragi-comédie et ballet, performed at the Tuileries on 17 January 1671, “les deux Baptiste” (as they were dubbed by the aristocratic writer Madame de Sévigné) engaged in a partnership which encompassed ten different works.” Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, the comédie put on for the king’s entertainment at Chambord in October 1669, represented a decisive staging point for Molière and Lully, as they subsequently became the exclusive purveyors of spectacles commanded for Court entertainments.

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Le mariage forcé “Suite” (Tonkünstler Orchestra; Dietfried Bernet, cond.; Hilde Langfort, harpsichord)

The collaborations between Jean-Baptiste Lully and Jean-Baptiste Poquelin assured that both men realized their utmost potential. The violinist-composer and dancer tested out a completely new genre, the tragédie lyrique, which draws together Italian and French elements. Simultaneously, the actor-author delivered comic and critical power for his theatre. “Through their partnership, they were going to make a success in “mixed entertainments,” typical of Baroque taste, where language, singing, dancing, “symphonie” and stage décor were all combining and blending.” Both also performed together onstage as singers, dancers, and as comedians.

Works of Molière Volume 1, 1739

Molière was, without doubt, a consummate showman and entertainer, and he “treated music as being a fully-fledged feature within his overall creative activity.” In fact, Molière was famous for fostering musical forms that were fashionable with the public, “making use of iterations modeled on the musical practices of repeats and variations, and abrupt changes of tone or disguise.” Molière was clearly part of the intellectual debate on music of the period, confirming “music as an art of pleasure, as a display of improbability, and as a source of that brilliant theatrically which enables it to function in partnership with a dramatic plot.”

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Le marriage force “La, la, la, bonjour” (Jerome Correas, harpsichord; Les Paladins; Jerome Correas, cond.)

Painting of Louis XIV and Molière by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Shortly before his death, Molière had a major falling out with Lully. I suppose it was inevitable, as the comédie-ballet essentially sees comedy and ballet struggle for stage space. The most probable cause of the feud was centered on the establishment of the royal opera privilege. Lully was looking to leave behind the comédie-ballet in order to focus on the development of a new genre, the French opera. King Louis XIV was delighted, as he saw opera as a preferred artistic means to demonstrate his power and eventually granted Lully the French opera privilege.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Molière decided to continue producing comédie-ballet and found a new collaborator in Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704). This new partnership was a resounding success, and for a revival of Le marriage force, Molière substituted Lully’s original composition with music and text by Charpentier. The crowd went wild, and Lully was not amused. He even went as far as obtaining a royal ruling, which forbade comedians in Paris from employing more than six singers and six instrumentalists in their performances. “This marked the beginning of a conflict for monopolistic control which would stir up cultural life until the end of the ancien régime.”

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Le bourgeois gentilhomme

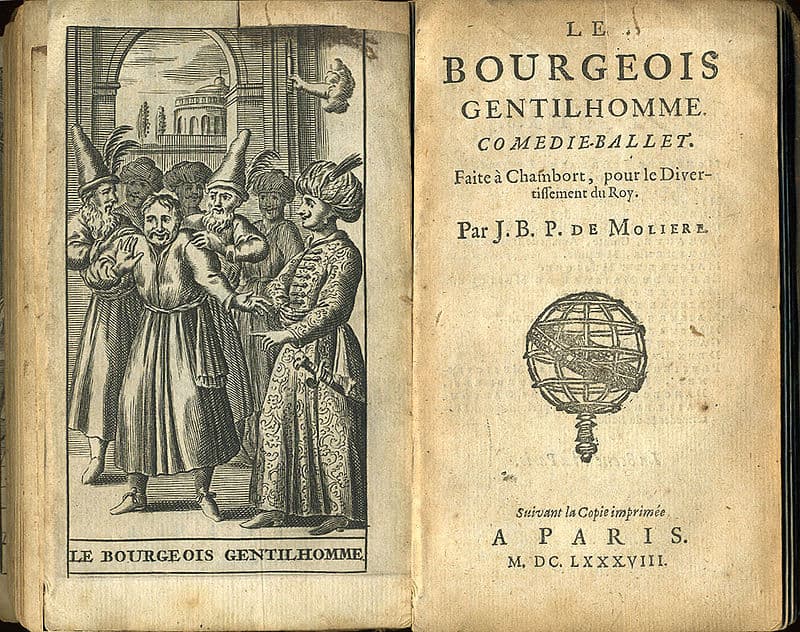

Be that as it may, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, commonly translated as the “Middle-Class Aristocrat,” marked the high point of the Molière and Lully collaborations. This play intermingled with music, dance, and singing “satirizes attempts at social climbing and the bourgeois personality, making fun both at the vulgar, pretentious middle-class and the vain, snobbish aristocracy.”

Molière’s Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, 1688

As has been pointed out, the title itself is oxymoronic, as a nobly-born individual could not be a bourgeois gentleman. The central character in the play is Mr. Jourdain, a middle-aged bourgeois who wants to rise above his middle-class background and be accepted as an aristocrat. He wears expensive clothes and learns the gentlemanly arts of fencing, dancing, music, and philosophy, and generally manages to make a fool of himself. His intelligent wife urges him to return to his senses, but he keeps on loaning money to a cash-strapped nobleman. He also dreams of having his daughter Lucile marry into the aristocracy, but Lucile is in love with the middle-class Cléonte. Cleverly, he disguises himself as the son of the Sultan of Turkey. Jourdain is delighted, and the play ends with a ridiculous wedding ceremony called the “Ballet des Nations,” a ballet within the ballet.

Gabriel Fauré: “Sérénade du Bourgeois gentilhomme” (Marc Mauillon, baritone; Anne Le Bozec, piano)

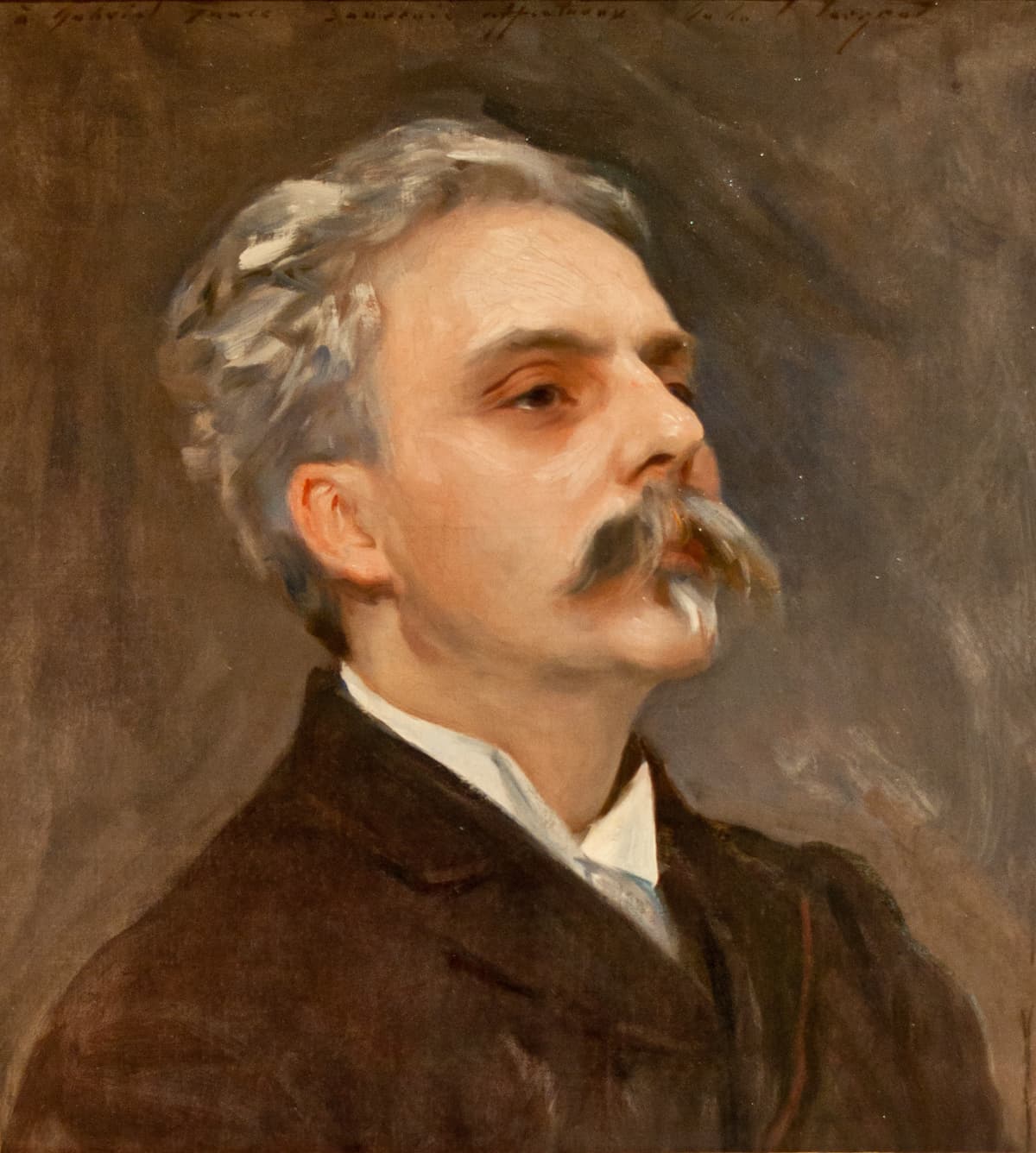

Portrait of Gabriel Fauré by John Singer Sargent

Lully’s music opens with an Overture in “the French style,” followed by various ritournelles that alternated with solo songs. Concluding the first Interlude we find the dancing master demonstrating his art. As his dancers begin he calls out the name of the specific dances: Air, Sarabande, Bourrée, Gailiarde. This dance sequence concludes with the “Canarie,” a quick, triple-time dance originating from the Canary Islands, lending itself to colorful accompaniment with guitar and tambourine. Various dances are interspersed throughout Act 2 and 3, and in Act 4 we find the famous “Ceremony of the Turks,” hailing the arrival of the Muslim scholar, dervishes, and other Turkish dancers and musicians. For the concluding “Ballet of Nations,” Lully provides dances of Spanish and Italian origin to accompany pantomime characters from the commedia dell’arte.

Le Bourgeois gentilhomme

Lully’s original incidental music for Le bourgeois gentilhomme was frequently revamped, arranged, and substituted by new compositions. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) was working on modifying Lully’s music when he decided to compose a little song in madrigal style entitled “Sérénade du Bourgeois gentilhomme.” The Sérénade is the first music we hear in Act I Scene 2 of the play, and it is part of the music lesson for Monsieur Jourdain.

Richard Strauss: Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (Der Bürger als Edelmann) “Suite,” Op. 60 (Norwegian Chamber Orchestra; Terje Tønnesen, cond.)

Jourdain is attended by both the Maistre à Danser and the Maistre de Musique. The music master says that he wishes M. Jourdain to hear the serenade that he has required to be set to music, as one of his pupils has fulfilled the commission. “Effortlessly offensive, M. Jourdain, who believes he merits only the very best, asks why a mere pupil, rather than the master himself, has done the job.” He then asks one of his Laquais for his robe in order, he says, to hear the music better. After the performance M. Jourdain judges the song to be ‘lugubre,’ and he requires the music master to brighten it up, a little bit here, and a little bit there.

Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Richard Strauss and his librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal weren’t interested in particular scenes, but rather interested in a two-act adaptation of Molière’s Le bourgeois gentilhomme. The play would be performed with new incidental music by Strauss, and the concluding ballet entertainment, the “Ballet des Nations,” of Molière’s original play would take the form of a new opera, Ariadne auf Naxos. However, it was not enough to provide an opera within a play, so they decided that Ariadne would itself contrast and combine mythical figures interloping with characters from a commedia dell’arte troupe. The result is hilarious, and the Strauss “Suite” a concert-hall favorite.

Emmanuel Bondeville: L’Ecole des Maris, “O ciel, pardonne encore….” (Natalie Dessay, soprano; Monte-Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra; Patrick Fournillier, cond.)

Emmanuel Bondeville

Molière continued to provide inspiration for composers in the 20th century, including Emmanuel Bondeville (1898-1987). He started his career as an organist at the church of Saint-Nicaise in Rouen and Notre-Dame in Caen. Consequently, he started to compose works for piano, symphonic poems, opéras-comiques and opéras. From 1949 to 1951 Bondeville was director of the Opéra-Comique, followed by a similar position at the Opéra de Paris from 1952 to 1969. Bondeville was married three times, and his interest in Molière’s L’école des femmes is possibly anchored in his personal life.

Molière’s L’école des femmes

That play depicts a mature man who is so intimidated by femininity that he resolves to marry his young and naïve ward Agnès. Having groomed her since the age of 4, he places Agnès in a nunnery until the age of 17 to keep her too ignorant to be unfaithful to him once they are married. In the end, all scheming, of course, turns out to be useless. Bondeville puts his own spin on the story, and his opéra-comique L’École des maris premiered in Paris in 1935.

Stefan Wolpe: “Stage Music” for Molière’s Le malade imaginaire (Recherche Ensemble; Werner Herbers, cond.)

The three-act comédie-ballet Le malade imaginaire (The Hypochondriac) by Molière premiered on 10 February 1673 at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris. It was to be Molière final work, and since he had already fallen out with Jean-Baptiste Lully, Marc-Antoine Charpentier provided the dance sequences and musical interludes. In this outrageously funny masterpiece, the hypochondriac Argan wants his daughter Angelique to marry a doctor so he can save on his medical bills. She, however, is in love with another young man named Cleante. When Angelique refuses, Argan gives her four days to agree or become a nun. Hilarity ensues when the entire household tries to change his mind. Eventually, he is convinced when, while pretending to be dead, he discovers that his new wife is only in it for the money, but his daughter truly loves him. He consents to her marriage with Cleante. Argan, in turn, is persuaded to become a doctor and treat himself.

Stefan Wolpe

Stefan Wolpe (1902-1972), a student of Franz Schreker and Feruccio Busoni in Berlin, took on the challenge of writing incidental music for the play in 1934. It freely mixes twelve-tone technique with diatonic episodes and other methods of tonal organization, and Elliot Carter famously said of Wolpe’s music that, “he does everything wrong and it comes out right.”

Nino Rota: Le Molière Imaginaire, “Suite” (Norrköping Symphony Orchestra; Hannu Koivula, cond.)

Maurice Béjart

In 1976, Maurice Béjart, one of the most important choreographers of the second half of the 20th century, asked the composer Nino Rota to take part in a project to celebrate the tercentenary of the death of Molière. As such, on 3 December 1976, the ballet-comedy Le Molière Imaginaire was first performed in Brussels. A couple of years later, Rota prepared a suite from the ballet music, which was once been described as “…a celebration with tragic pauses,” and “a celebration veiled by a gentle and irreverent melancholy.” According to Béjart, “For Molière, a grimace, a burst of laughter, or a song are as important as a beautiful line. Nature is life, Molière is alive.”

Nino Rota

In his score, Rota is recreating 17th-century France, yet by mixing different styles, he “maintains a poetic and expressive idiom uniquely his own.” Henry Purcell (1659-1695), meanwhile, had composed the semi-opera King Arthur, or The British Worthy to a libretto by John Dryden in 1691. It chronicles the battles between the Britons and the Saxons, and includes a sobbing ground-based air “La Mort de Molière,” which also includes a somber choral eulogy.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Henry Purcell: King Arthur, or The British Worthy, “La Mort de Molière” (Maurice Bevan, baritone; Deller Consort; Clemencic Consort, René Clemencic, cond.)