Although she and her talents were central to the work of her husband and creative partner Giacomo Rossini, there is no English language biography of Isabella Colbran.

We want to change that. So consider this a basic overview of her story while we wait for a specialized biographer to tell the full story of Isabella Colbran’s extraordinary life!

Early Childhood

Isabella Colbran

Isabella Colbran was born on February 2, 1785, in Madrid, Spain. Her father was Giovanni Colbran, the head musician in Charles III’s court.

She must have shown musical talent at a very early age because when she was only six years old, she began studying music (specifically, voice and composition) with several of the best-known musicians in Spain, including castrati Carlo Martinelli and Girolamo Crescentini. By the time she was fourteen, she had published a book of songs.

Isabella Colbran – Il piè s’allontana

In 1801, when she was sixteen, she moved to Paris with her father and began working in Napoleon’s court. Later, father and daughter traveled throughout Europe, eventually choosing to settle in Italy.

Throughout her twenties, she was one of the most celebrated singers in the world, a favorite of royalty, the aristocracy, and other powerful people alike.

Life in Italy

In 1807, when Colbran was twenty-two, she made her debut at La Scala in Milan. Italy, she found, agreed with her.

That same year, she gave a concert that scholars believe fifteen-year-old Gioachino Rossini likely attended. He was studying music in Bologna at the time, and he almost certainly wouldn’t have passed up the chance to see her.

French writer Stendhal described her as “a beauty of the most imposing sort; with large features that are superb on the stage, magnificent stature, blazing eyes, à la crircassienne, a forest of the most beautiful jet-black hair, and, finally, an instinct for tragedy. As soon as she appeared [on stage] wearing a diadem on her head, she commanded involuntary respect even from people who had just left her in the foyer.”

Life in Naples

Rossini – Elisabetta regina d’Inghilterra – Isabella Colbran as Elisabetta

At the height of her creative power, she made a couple of fateful decisions.

First, she signed a seven-year contract with the Theatro di San Carlo in Naples.

She also embarked on a relationship with the powerful Domenico Barbaia, one of the savviest impresarios in Italy. This helped to guarantee her fame…and crush the local competition, which was never going to compete with Barbaia’s mistress.

In 1815, Barbaia, always on the lookout for new talent, hired Rossini to write an opera about Queen Elizabeth I. The decision would have both personal and professional repercussions. Twenty-three-year-old Gioachino Rossini was just beginning his career as an opera composer, and this was an extraordinary opportunity to write for one of the great voices of her generation. Between 1815 and 1823, he wrote eighteen operas for Colbran: an average of one every six months.

Not surprisingly, given how closely they were working together, sparks flew. Colbran broke things off with Barbaia and committed to Rossini instead. His relationship with her would prove life-changing.

Life With Rossini

In 1820, Colbran and Rossini collaborated on his most daring work yet: an opera called Maometto II, about a real-life Ottoman Sultan from the fifteenth century.

Rossini: “Maometto Secondo”

He made some bold artistic and structural choices. One of them was that toward the end of the opera, Colbran sang for over half an hour, never leaving the stage during that time.

The year was a fraught one, both personally and politically.

First, Colbran’s father died. One sign of how close Rossini and Colbran were at this time was that Rossini bought a cemetery plot for her father. This suggests that he thought of Colbran not as a temporary mistress but as a long-term partner, even if they hadn’t legally wed yet. In his will, Colbran’s father left his daughter a villa outside of Bologna. (This would become important later.)

That same year, there was also an attempted coup against the monarchy in Naples. Political instability in Naples, combined with the failure of his 1819 opera Ermione (a production that, of course, Colbran had starred in), convinced the couple it was time to leave.

Marrying Rossini

In November 1821, Rossini wrote to his father that he and Colbran were engaged.

After the first run of his opera Zelmira in February 1822, Rossini and Colbran traveled to Bologna, where, on 16 March 1822, the two were married in a church outside of town. She was thirty-seven, and he was thirty.

From this point on, Rossini began controlling pretty much every major aspect of Colbran’s life: from the money she had earned during her career to the property she had inherited. This legal and financial powerlessness of married women was common, but it must have been stressful for Colbran to feel her agency dwindling.

That season, Domenico Barbaia decided he wanted to bring the Naples opera company to Vienna. So the newlyweds traveled to Vienna together, and they were a great success. Prince Metternich, a powerful conservative statesman, was a big fan of Rossini’s operas, and six were mounted over the course of three months.

The End of Colbran’s Career

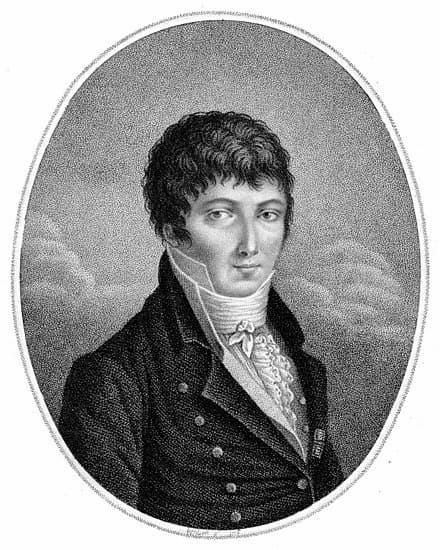

Girolamo Crescentini

However, storm clouds were brewing. Rossini wrote in his letters that Colbran was experiencing stage fright because she felt as if the quality of her voice was deteriorating.

While his wife worried for her career, Rossini threw himself into the Viennese music scene. He heard Beethoven’s Eroica symphony and met with the composer, who implored him to write more comedy…a genre he had largely ignored because Colbran’s strengths lay in drama.

Within months after their marriage, Rossini got to work on another opera for his wife called Semiramide, which premiered in Venice in February 1823.

Gioachino Rossini: Semiramide

Unfortunately, Colbran got bad reviews. As she feared, her voice was indeed deteriorating, and critics and audiences were noticing that she was having more and more trouble staying in tune.

In 1824, her lost voice forced her to retire from the stage for good.

Colbran’s Final Years

In 1830, Rossini’s widowed father moved into the villa that Colbran had inherited. Neither daughter-in-law nor father-in-law was particularly thrilled about this arrangement, but both grit their teeth and bore it.

Meanwhile, Rossini was gone most of the time in Paris, working and dealing with financial issues. He was unfaithful, cheating on his wife multiple times. Eventually he began seeing Parisian courtesan Olympe Pélissier, who evolved into a long-term partner.

He ended up suffering from a bout of gonorrhea, and at some point, Colbran became sick with it, too. Worse, she developed complications. During her illness, with no career to pursue, she sought distraction in gambling, a habit that quickly turned disastrous.

Needing an artistic outlet, she also returned to composing during this time. By the end of her life, she had composed four books of songs, dedicating them to Maria Luisa of Parma, Louise of Baden, Queen of Naples Julie Clary, and her castrato teacher Girolamo Crescentini.

She and Rossini broke up sometime in the 1830s and made their separation official in 1837. That same year, Colbran met Pélissier for the first time. Rossini scholar Denise Gallo writes that Rossini’s wife and mistress developed “a polite relationship.”

However, for what it’s worth, Rossini didn’t entirely abandon Colbran. He paid her money, and even though he was completely emotionally and physically absent, he apparently ensured she had high-quality medical care.

Meanwhile, according to legend, Colbran never fell out of love with her husband.

Colbran’s Death

In August 1845, Rossini heard that his former wife’s health was dangerously bad. In September, he went to the villa with Pélissier to see her for the final time. He emerged from Colbran’s chambers crying. Nobody knows what they said to each other.

After Colbran died on 7 October 1845, he sold her villa, unwilling to ever return. Although he composed intermittently and privately later on, Isabella Colbran’s death coincided with the ceasing of his heretofore productive creative life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Thank you for the story. Poor Isabella! We all wonder why Rossini stopped his music career so prematurely, but the death of Isabella is a plausible reason. Those womanizers are many times very dependant, psycologically, I mean, on their legitimate wife.

I am very fond of Rossini’s operas and know of his life more or less what any opera lover and goer knows, but I never studied deeply his life and works.

Something personal: My (French) grandmother was called Léontine, she was not a fanatic cook but she had created her own cannelloni recipe which she called “cannelloni à la Léontini”.

I don’t remember how I got connected with Interlude but I like the newsletter and I learn a lot from it.