Johann Strauss II’s waltz, An der schönen, blauen Danube (By the Beautiful Blue Danube or The Blue Danube), was only a mild success at its premiere at the concert of the Wiener Männergesang-Verein (Vienna Men’s Choral Association) on 15 February 1867. Strauss’ idea for the work came from a poem by Karl Isidor Beck (1817–1879), in which each stanza ends with ‘‘By the Danube, beautiful blue Danube.” This was Strauss’ inspiration, even though the Danube is not really blue and, at that time, didn’t even flow through Vienna.

Wilhelm Gause: Hofball in Wien, 1900 (Vienna Museum)

The first choral version, with text by Joseph Weyl, was a satirical commentary on Austria’s having just lost a war with Prussia (the Seven Weeks’ War). Strauss was writing a piece to life the nation’s spirit, and Weyl’s lyrics ridiculed ‘the lost war, the bankrupt city and its politicians: “Wiener seed’s free! Oho! Wieso?” (“Viennese be happy! Oho! But why?”)’. On its premiere, it received only one encore (hence was regarded as a failure by Strauss) and not only the choir but also the audience hated the lyrics.

Josef Kriehuber: Johann Strauss Sohn, 1853

Johann Strauss II: An der schönen, blauen Donau (The Beautiful Blue Danube), Waltz, Op. 314 (Vienna Johann Strauss Orchestra; Johannes Wildner, cond.)

Strauss made some changes to the music (and the Choral Association’s poet, Weyl, added words), but the piece found its audience after the purely orchestral version was played at the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris.

The work became extremely popular, and it’s reported that Strauss’ publisher printed over a million copies of the piano score. New lyrics by Franz von Gerneth (a member of the Austrian Supreme Court) gave the waltz a more dignified text (“Donau, so blau, so blau” (“Danube, so blue, so blue”)). Both the instrumental and choral versions have had their fans, but it’s the instrumental version that has held everyone’s interest.

One way contemporary composers showed their skills was by taking a well-known work and making their own variation sets on it.

German composer Max Reger (1873–1916) made his improvisation on The Blue Danube in 1898, becoming one of the first to use Strauss’ work as the basis for his ideas.

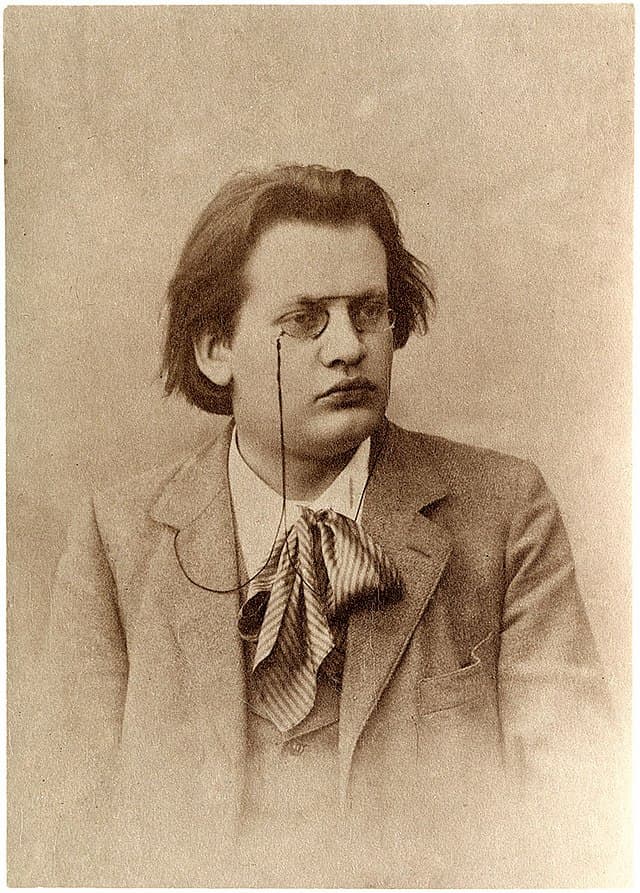

Max Reger, 1896

Max Reger: Improvisation über ‘An der schönen blauen Donau’, WoO III/11 (Konstantin Scherbakov, piano)

Polish composer and pianist Adolph Schulz-Evler (1852–1905) wrote some 50 piano works, but it is his paraphrase of The Blue Danube as a set of concert arabesques that he’s known for today. These were published in 1900, 37 years after the original’s premiere, and because of its virtuosity and the highly ornamented (arabesque) style is more often recorded than performed live.

Adolph Schulz-Evler: Concert Arabesques on motifs by Johann Strauss, “By the Beautiful Blue Danube” (Hando Nahkur, piano)

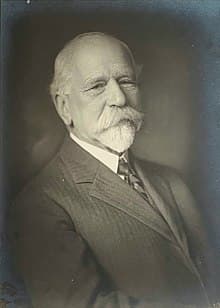

Russian composer Eduard Schütt (1856–1933) was aided by Anton Rubinstein in persuading his father that music was his future. Around 1910, his Leipzig publisher, Cranz, put together a collection of his concert paraphrases of Strauss’ works which included some of Strauss’ most famous waltzes and other works:

Fledermaus-Walzer, Kuss-Walzer, Geschichten aus dem Wiener Wald, Schatz-Walzer, Rosen aus dem Süden, Dorfschwalben aus Österreich, Künstlerleben, O schöner Mai!, Morgenblätter, An der schönen blauen Donau, Wiener Blut, Frühlingsstimmen, Wein, Weib und Gesang, and Freut Euch des Lebens. No. 10 is his paraphrase on The Blue Danube.

Eduard Schütt

Eduard Schütt: Concert Paraphrases on J. Strauss’s Waltz Motifs, No. 10 – An der schönen, blauen Donau (Cornelia Sonneck, piano)

Hungarian virtuoso pianist György Cziffra (1921–1994) started his career at age 5 improvising popular show tunes, eventually attending the Franz Liszt Academy. He was considered one of the greatest virtuoso pianists of the 20th century and was known for his recordings of Liszt’s, Chopin’s, and Schumann’s works. His transcription of The Blue Danube from around 1955 is considered technically demanding. It is a fitting tribute to the power of his imagination, even with a well-known piece of music.

György Cziffra

György Cziffra: Paraphrase sur le Beau Danube bleu (After Johann Strauss II) (György Cziffra, piano)

Other composers did their paraphrases as well, including American composer W.L. Hayden, who made one of the first arrangements under the title of Gems of the Beautiful Blue Danube Waltzes in 1874, Paolo Giorza who published his Caprice de concert on ‘Blue Danube’ waltz in Australia in 1883, and Oscar Straus as part of his set of fantasies entitled Isadora Duncan, op. 135, in 1904. Although these works have not been recorded, they are testament to the work’s international appeal even early in its life.

An arrangement of the work for piano 4-hands by Gregg Anderson as the Blue Danube Fantasy is one of the latest versions of the work. The composer says, ‘ this concert fantasy for one piano, four hands attempts to illustrate the striking parallels between four feet traversing a dance floor and four hands navigating a piano keyboard’. He goes on to request that, although it may be easier to play on two pianos, that players play it as written on one piano. The performance is about ‘the act of dancing as much as it is the act of making music’.

Greg Anderson: Blue Danube Fantasy (after waltzes by Johann Strauss II) (Ayumi Iga, Masatoshi Yamaguchi, piano 4 hands)

This may make more sense in a video:

Strauss/Anderson | Blue Danube Fantasy

One take-off of the work in movies was in André Previn’s score for It’s Always Fair Weather, where three war-time buddies get back together after a 10-year separation only to realize that their former friendship hasn’t held up over time.

Michael Kidd, Dan Dailey, and Gene Kelly in It’s Always Fair Weather (1955)

André Previn: It’s Always Fair Weather (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) – The Blue Danube (I Shouldn’t Have Come) (Gene Kelly, Ted Riley; Dan Dailey, Doug Hallerton; Michael Kidd, Angie Valentine; MGM Studio Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

It’s even funnier in the film itself where common courtesy with each other is strongly contrasted by their inner feelings.

Blue Danube (I Shouldn’t Have Come) | It’s Always Fair Weather

The life of Strauss’ image of the Danube and its association with Vienna has been maintained for over 160 years and is still one of Strauss’ longest-lived musical ideas. It is used in movies, such as in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where it’s used for the elegant dance of the space plane’s alignment with the space station and to underscore the idea and image of weightlessness. The whirling of the space station matches the whirling of the music in a way unmatched in film.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – ‘The Blue Danube’ (waltz) scene

In Titanic (1997), where it’s used for Jack’s entry into First Class down the grand staircase, it symbolizes old money and old society.

Titanic: Jack comes to first class

It started as the waltz of old Vienna and turned into the dance of all of tomorrow. What’s your image of the Beautiful Blue Danube?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter