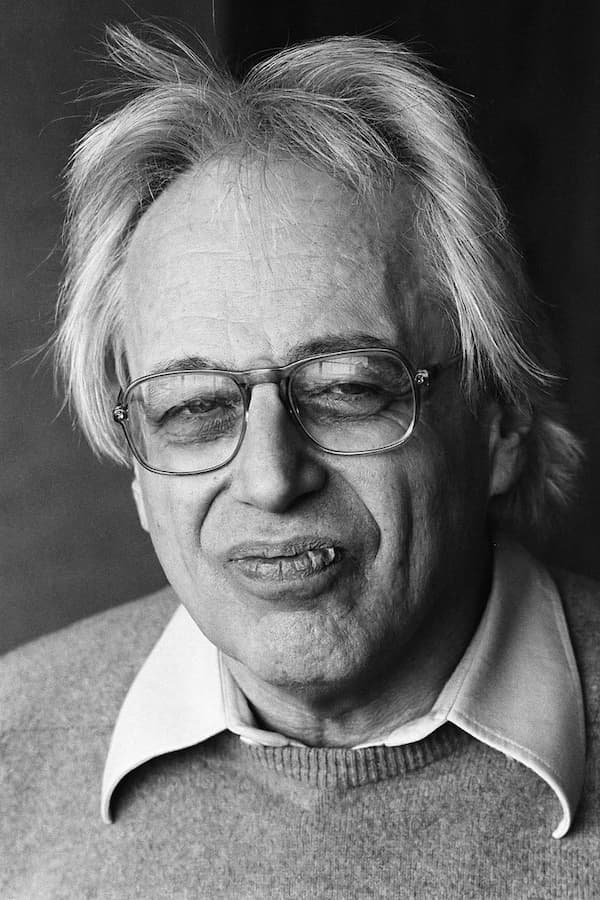

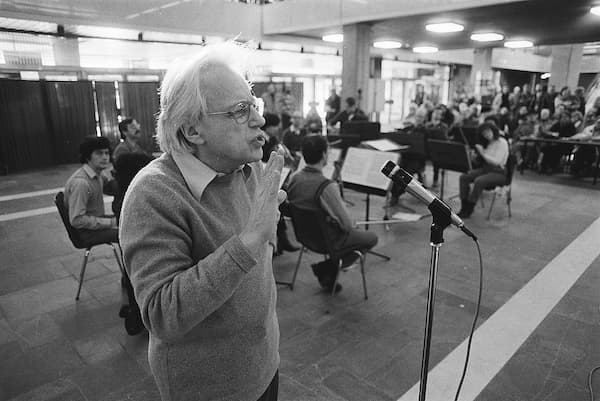

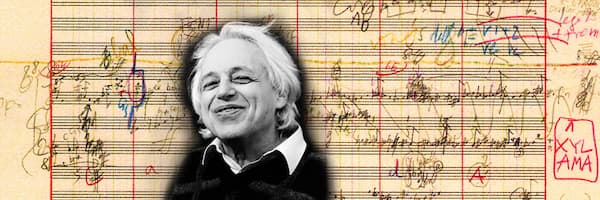

The Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923-2006) made his name by developing a process of interweaving different strands of sound into a complex polyphonic fabric, “deriving the shape and momentum of the music from barely perceptible changes in timbre, dynamics, density, and texture.”

György Ligeti (1984)

For Ligeti, his enthusiasm for science and his insatiable curiosity were constant sources of inspiration and questioning. “All culture,” he once wrote, “the whole world, are material of art.” Folk music proved to be a great source of inspiration as Ligeti expanded the limits of tonal music by studying, among others, the folk music of the Balkans and African music, especially sub-Saharan music. It was the rhythmic richness of polyrhythmic drumming and the coexistence of server layers of sound that opened up unfamiliar possibilities and created a new imaginary musical folk universe. Over a period of roughly seventeen years, Ligeti composed eighteen Études pour piano, with the first book of six Études issued in 1985. A second book was composed between 1988 and 1994 and features eight Études, while the third and final book, composed between 1995 and 2001, includes four more Études. Ligeti originally intended to issue only twelve Études, in two books of six each by following Debussy’s model. Apparently, the work kept growing because “he enjoyed writing the pieces so much.” The third book, in fact, is unfinished, as illness and death brought this project to an end.

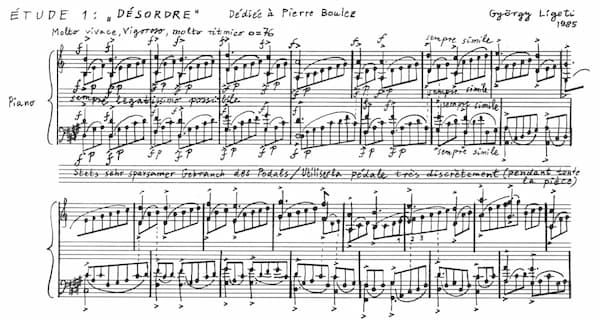

György Ligeti: Études for Piano (Book 1), No. 1 “Désordre”

No other set of solo piano works composed within the past fifty years has been the topic of more scholarly publications. “Despite their considerable difficulty, concert pianists continue to program them, and they have entered the standard repertoire so readily that they figure conspicuously in lists of acceptable etudes for auditions and competitions. It is no exaggeration to say that as a set, these etudes constitute the most important work for solo piano in the latter half of the twentieth century.” Ligeti was not a piano virtuoso, and he was himself not able to play them, as “his initial impulse was, above all, my own inadequate technique.” Yet, Ligeti was certainly eager to leave his own legacy on the genre. Although he composed the eighteen études independently, the sequence of works of his three books results from a thoughtful process. “Therefore, the order of études, when played in their entirety, should be respected. Each book forms a cycle, not a collection of independent pieces.”

György Ligeti: Études for Piano (Book 1), No. 2 “Cordes à vides” (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano)

György Ligeti’s Etude “Désordre”

The titles of various études are a mixture of technical terms and poetic descriptions. Ligeti compiled a vast reservoir of titles, and these titles frequently changed between inception and publication. In addition, the composer would frequently assign titles after the work had been completed. Be that as it may, the title of the first etude, “Désordre” (Disorder), seems to accurately describe the rhythmically contorted narrative of the piece. While doing his research on African music, Ligeti wrote, “In Africa, cycles or periods of constantly equal length are supported by a regular beat, which is usually danced, not played. The individual beat can be divided into two, three, sometimes even four or five elementary units of fast pulses. I employ the elementary pulse as an underlying grid… in Désordre for accents shifting, which allows illusory pattern deformations to emerge. The pianist plays a steady rhythm, but the irregular distribution of accents leads to seemingly chaotic configurations.” Actually, Ligeti combines two distinct musical processes. An additive metric pattern of 5+3 or 3+5 and “a simultaneous sounding to triple patterns in one of the pianist’s hands and duple pattern in the other.” Ligeti builds rhythmic complexity with extraordinary force and energy that reaches a furious climax and then vanishes. Adding to the complexity is the fact that the right-hand plays only on the white keys while the left hand is restricted to the black keys, creating diatonic music in the right and pentatonic music in the left hand.

György Ligeti: Études for Piano (Book 1), No. 3 “Touches bloquées” (Cathy Krier, piano)

György Ligeti

Ligeti once described himself as “like a blind man in a labyrinth, feeling his way around and constantly finding new doorways and entering rooms that he did not even know existed.” Among his fellow composers, Ligeti, alongside Pierre Boulez, were considered the finest compositional minds in their generation. And in his series of études for piano, the most dazzling piano pieces of our time, Ligeti “had glimpsed sources of the instrument’s sonority no one before had exploited.” But what is more, Ligeti never altered his stance on meticulousness and honesty, as making modern music meant “making new sounds and engaging in experiments of the kind that did away with the old criteria.” In this, together with Pierre Boulez, “he was the conscience of contemporary music.” As such, it should not come as a surprise that the first three études of Book 1 are dedicated to Pierre Boulez on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. Boulez always championed Ligeti’s compositions, and Ligeti, early in his career, prepared meticulous scholarly treatises analysing Boulez’s works. The second étude of Book 1 carries the title “Cordes à vides,” or “Open Strings.” The entire etude is based on the perfect interval of a fifth, the tuning intervals of the strings of the violin, viola, and cello. Ligeti composed a nuanced rhythmic crescendo, a terraced metered acceleration from the beginning to the end. “This étude starts with ten measures of slow eighth notes in both hands, after which the etude becomes increasingly rhythmically complex, featuring fragmented hemiolas and a dramatically thickening texture that seems to instantly evaporate upon reaching the limits of the keyboard.”

György Ligeti: Études for Piano (Book 1), No. 4 “Fanfares”

György Ligeti

In “Touches bloquées” or “Blocked Keys,” Ligeti interlocks two rhythmic patterns. While one hand depresses certain notes, the other plays a rapid and constant stream of eight notes intersecting with the blocked keys. This produces quirky asymmetrical rhythms and a kind of stuttering that would otherwise be difficult to produce. But it’s not enough, as Ligeti severely increases the technical demands on the performers. The left hand not only depresses certain notes, it also participates in the actual process of playing, and the right hand not only streams single lines but also plays an occasional chord. “Fanfares” presents a seven-note ascending scalar ostinato 208 times, in a fascinating a process of continuous development. That particular rhythmic ostinato originates in Ottoman musical theory. Termed “aksak,” it is a system “in pieces or sequences, executed in a fast tempo, are based on the uninterrupted reiteration of a matrix, which results from the juxtaposition of rhythmic cells based on the alternation of binary and ternary quantities, as in 2+3, 2+2+3, 2+3+3, etc.” The name literally translates as “limping,” “stumbling,” or “slumping,” and it is used in Turkish vocal and instrumental dance music. For Ligeti this becomes an étude highlighting irregular and additive meters.

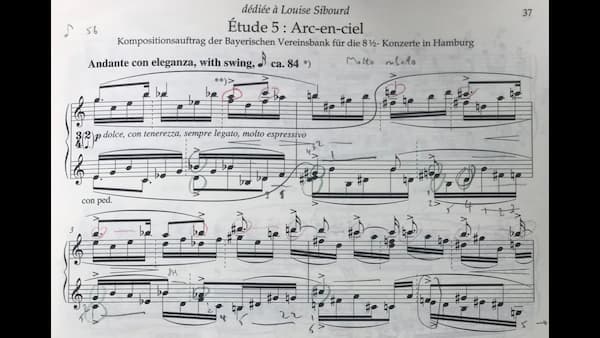

György Ligeti: Études for Piano (Book 1), No. 5 “Arc-en-ciel”

György Ligeti’s Etude “Arc-en-ciel”

Dedicated to the pianist Louise Sibourg, “Arc-en-ciel” (Rainbow) forms various musical colour bands within a multi-stranded rhythmic texture. A recurring descending chromatic line and music that rises and falls in arcs provide the evocation of a rainbow. This étude is dedicated to Louise Sibourd, and it is the most clearly triadic of the set. “The piece has a floating quality due to the slow tempo, moderate harmonic rhythm, almost static melody, and high register. There is a general impression of the ternary form: the outer sections display a stable range, undulating dynamics, and generally steady tempo, albeit with considerable rubato, while the central section is characterized by violent registrar and dynamic outbursts and frequent hyper-expressive variations of tempo.” The concluding étude in Book I, “Automne à Varsovie”, references the “Warsaw Autumn,” an annual festival of contemporary music. The composer explains, “Chopin, acting as my model, came to my aid. The spiritual and poetic content and the concrete nature of the instrument and hands do not form constraints as my compositional imagination is unconsciously pre-programmed by these technical and anatomical factors.” Ligeti refers to this étude as a “tempo fugue,” a study in polytempo consisting of a continuous transformation of the initial “lament motif.” That motif undergoes various rhythmic diminutions and augmentations, as it descends to the lowest ranges of the keyboard. As Ligeti explained, “at the centre of my compositional intentions in the études lies a new conception of rhythmic articulation.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

György Ligeti: Études for Piano (Book 1), No. 6 “Automne à Varsovie” (Idil Biret, piano)