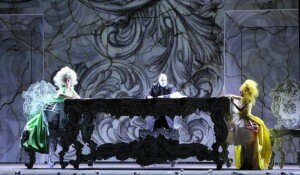

La Cenerentola by G. Rossini. Lirica Season 2018 © Padova Cultura

Because the city we live in, Perugia, the capital of Umbria (300,000 people) does not have an opera season despite having 3 Opera houses!

So Padua: what a wonderful surprise! A modern-old city in the Veneto with multiple shopping galleries, sparkling in the evening, rich with garlands of flowers, lights touting all the famous Italian brand names such as Pucci, Prada, Max Mara, Bottega Veneto, even Benetton is making an elegant show of its usually low-cost, low-taste product.

And for the glorious finale, Hermès for people who do not need to look at price tags.

But back to Padua and La Cenerentola, which was created by Rossini in 24 days with a libretto by Ferretti finished in 22 days; they were in a nervous competition and gave us a work of genius.

La Cenerentola by G. Rossini. Lirica Season 2018 © Padova Cultura

At the première, the reception of the opera was disappointing with little applause and a lot of “fischi” (whistles of disapproval). The public 200 years ago might have been right since everything for that first performance had been done in a hurry. The singers had only 2 rehearsals and apparently were “paralyzed with fear” about attacking this 3-hour formidable work.

To give it its full name, the opera is La Cenerentola, ossia La bontà in trionfo (Cinderella, or Goodness Triumphant) and the story involves the 2 daughters of Baron Don Magnifico, Clorinda and Tisbe (the two ugly sisters), who are plotting ways to get married, and Angelina (Cenerentola), his protégée (figliastra/stepdaughter), who they torment.

La Cenerentola by G. Rossini. Lirica Season 2018 © Padova Cultura

Next follows Don Ramiro himself, disguised as Dandini, his valet. Alidoro tells him of Cenerentola’s kindness and he starts to pursue her. Finally, Dandini, the valet, enters, clothed as the Prince, the two sisters are escorted to the Prince’s party, and Alidoro and the disguised Prince start to interrogate Don Magnifico about his rumoured third daughter. Don Magnifico declares that she has died, notwithstanding the fact that she’s standing right next to him. All of this is just the first scene!

So you can see for yourself how complicated the rest of the story will be, since we have met in a short while all the performers who will proceed to tangle and untangle this by-now-usual scenario of Italian opera buffa. Everybody is disguised as somebody else and all the boys and girls are testing each other’s fidelity.

La Cenerentola by G. Rossini. Lirica Season 2018

Annalisa Stroppa © Padova Cultura

As I sit in the audience, an unfortunately unending set of questions engages me:

• Is this a teatro comico accompanied by a cast of super singers desperate to unload a wickedly difficult score?

• Who are these annoying untalented Tyrolean mimes that are disturbing everybody on the stage and in the hall? Why are they there??

• Is this an attempted solution for the 30% unemployment of young people in Italy?

• Is this a crowd of amateurs who entered the Opera by mistake through the backdoor?

• Why is this musically wonderful all-male choir dressed in shabby “armée de salut” hand me downs?

• Why is the chorus furiously rope fighting in the middle of act one?

• What is the sense of the silly school class, or as they say in Italian, “che c’entra?” (What does that have to do with anything?)

• What are these unruly children doing, running around on the stage between the legs of the singers?

• Who are these singers who can’t sit still for a second, constantly performing silly repetitive gags?

La Cenerentola by G. Rossini. Lirica Season 2018

Iirina Ioana Baiant © Padova Cultura

The cast: what a spectacular group of singers, valiantly fighting to have their words heard in this over-directed pandemonium.

Starting at the top is Annalisa Stroppa, the mezzo Angelina: she has all the rainbow colours of a splendid voice: the high and the mezzo and even the low notes, then the warm tone and the veloute colour, as well as the Rossini trills.

By rights she is a diva who should have had warmer applause than the economical one awarded.

Coming a close second is Alidoro, the super bass of Gabriele Sagona whose full-throated voice was resonant and warm with a splendid soffragio.

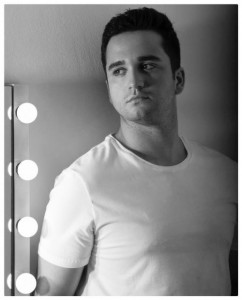

Gabriele Sagona

© www.opera-online.com

The rest of the cast are all splendid, especially sister Clorinda (Irina Ioana Baiant, the Romanian star), whose soprano voice filled the hall up to the 4th ordine loggione (gallery).

The quartet (of Act 1), and particularly the frenzied finish by soloist and choir of orchestra concluding the first act, are a special dish for Rossini fans.

The second act abounds in marvellous sextet singing, I can’t think of an Italian opera where so much ensemble work is heard.

Xabier Anduaga

© http://www.gmartandmusic.com

The “buca” of Teatro Verdi is very much open and is carried into the heart of the platea (stalls), which makes the orchestra sound very sharp and alive.

Maestro Antonello Allemandi led this difficult task with a sure hand. I give a particular bravi to the wind instrument players who blended so well with the Rossini vocal thrills.

We mentioned the drab haberdashery of the male choir but this took little off their excellent singing. As with other operas of Rossini, the choir holds a major role carrying important messages for those interested in understanding the score.

Padua’s Teatro Verdi, with its four ordine and curiously effaced ceiling fresco, was sold out but the non-elegant middle-aged public did not work hard enough to compensate this monumental work and the star singing.

Finally a note on the program (distributed free… bravo!): why give us the whole libretto verbatim when there was a projected libretto above the curtain? Why not give us pictures and biographies of the wonderful performers?

Please…

For finish on a positive note: please redo this monumental work semi-scenico (semi-staged) with the superb soloists plus chorus and orchestra, and minus the Barnum circus.

I would willingly travel 5 hours to hear this again.

Padua

Teatro Verdi, 29 December 2018.

Annalisa Stroppa & Kenneth Tarver “Un soave non so che” (La Cenerentola)