The concept of percussion is rather easy: find something, hit it. Eventually, the development of hitting things to make definite sounds led to the development of the timpani – a tunable drum used to supplement the bass section of an orchestra.

The timpani, also known as kettledrum, is one of the most important percussion instruments because it can change pitch. The bowl of the instrument is traditionally made of copper and modern ones may be made of fibreglass. The head of the instrument was calfskin or, now, plastic. The important part is that the drumhead is attached to a hoop that is fitted to a metal ring that controls the tuning.

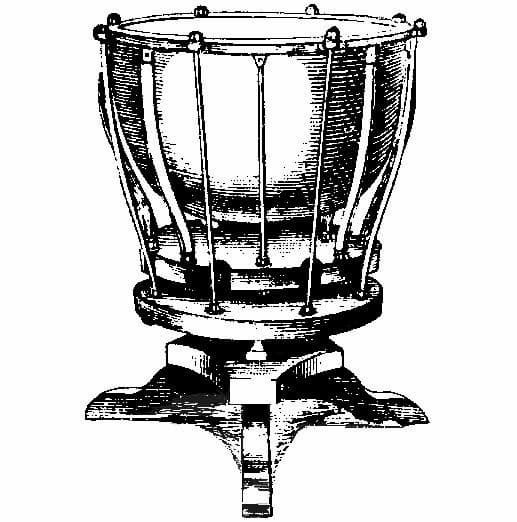

Baroque Timpani with hand screws (Adams Percussion)

The tuning on the baroque model is done through hand screws attached to the hoop and the body of the instrument.

Hand Screws (Adams Percussion)

These would be adjusted in opposing pairs to keep the pressure on the drumhead as even as possible. To change the pitch would take some time, as three pairs of screws would have to be turned to adjust the pitch.

To speed up the tuning process, other methods were developed. British inventor Gerhard Cramer designed a system where rotating the drum changed the pitch. His model was updated and improved in 1815 by Dutch musician and inventor Johann Stumpff.

Stumpff rotating tuned drum

Since the rotating method required that the percussionist put down his mallets to adjust the pitch, the next development was to have a single master screw that adjusted all the hand screws at once. This is known as Einbigler tuning after its inventor. Johann Kaper Einbigler, who developed this in 1836.

Einbigler single-screw adjustment (Photo by Scott Weatherson) (Florence: Accademia Gallery)

Finally, in 1840, a German gunsmith designed a drum that could be retuned by a foot pedal, rather than having to use the hands. This was finally codified in 1881 with the Dresden foot pedal, which is still used today.

Dresden foot pedal model (Ludwig Drums)

So, now that we have the drums tuned, how are these used? Given their size, they can’t be carried by percussionists when marching – so they are normally mounted on horseback. You will note that this horse is not the lighter Arabian horse that the rest of the cavalry uses, but a heavier horse.

Drum Horse of the Queen’s Household Cavalry, 2007 (Photo by Ultra7)

The Mounted Band of His Majesty’s Life Guard Dragoons

Timpani were used with both sacred and secular music and today, we mostly associate them with orchestral music. Most orchestral players use three or four timpani of different sizes so that they can cover the pitches needed. If more are required, you may see two timpani players, each with their own set of drums.

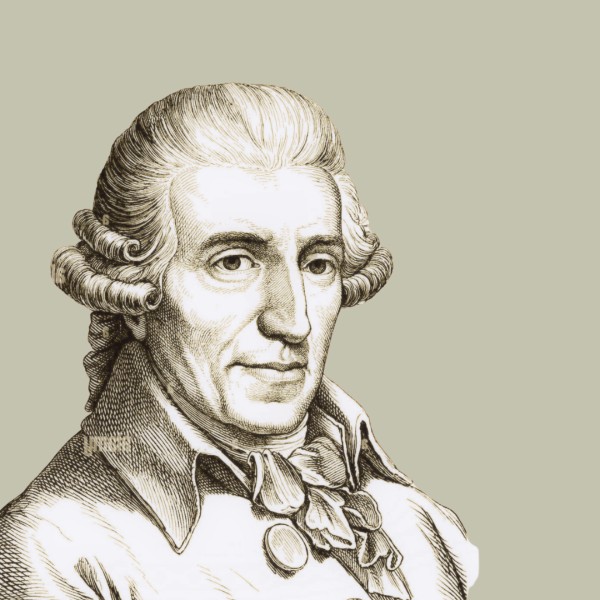

Haydn was an occasional timpanist and made an impressive start to his Symphony No. 103 in E Flat major with a timpani roll, which gave the symphony its nickname of the Drumroll.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 103 in E-Flat Major, Hob.I: 103, “Drumroll” – I. Adagio – Allegro con spirito – Adagio – Tempo I (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Eugen Jochum, cond.)

Other symphonies with significant timpani parts include Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, with its menacing timpani rumbling in to announce the thunder of the storm.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68, “Pastoral” – IV. Thunderstorm: Allegro (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Gianandrea Noseda, cond.)

Always one to push the orchestration envelope, in his Grande Messe des Morts, Hector Berlioz called for 8 pairs of timpani, each set with two players, giving him a pitch range of the entire E♭ major scale, plus G♭ and A♮.

Hector Berlioz: Grande messe des morts, Op. 5, “Requiem” – Dies irae (Giuseppe Sabbatini, tenor; Vienna State Opera Chorus; Wiener Singakademie; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Bertrand de Billy, cond.)

One of the first concertos for timpani, written around 1780, actually called for eight timpani. Fischer, theatre director of the Ludwigslust Palace near Schwerin in the employ of Herzog Friedrich Franz I, probably wrote the work for entertainment in the main ballroom. The eight timpani were tuned to a C major scale, so no retuning was involved in the performance.

Johann Carl Christian Fischer: Symphony with eight obligato timpani – I. Moderato (Alexander Peter, timpani; Dresden Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra; Alexander Peter, cond.)

One composer who took advantage of the new Dresden foot-pedal tuning possibilities was Richard Strauss. His writing for the timpani in his opera Der Rosenkavalier treated the drum as though it were another member of the bass section of the orchestra, with frequent pitch changes that could be done with one foot while the hands were busy playing a different drum. In the final waltz of the opera, the timpani provides a walking bass line.

Richard Strauss: Final Waltz from “Rosenkavalier” – Suite, with KEVIN RHODES

One of the greatest timpani battles comes at the end of Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 4, ‘The Inextinguishable’. From opposite sides of the stage, two timpanists, playing dissonant tritones, battle the rest of the orchestra for dominance over the tonality of the work. In the end, the orchestra wins out with its F major and the timpani have to retreat.

Carl Nielsen: Symphony No. 4, Op. 29, FS 76, “The Inextinguishable” – IV. Allegro (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Zubin Mehta, cond.)

When he was commissioned to write his Concerto for Timpani and Orchestra of 1983, American William Kraft had doubts that there was enough musical interest in a timpani’s sound to sustain a full concerto. As he explored the sonic capabilities of the instrument, he found more than enough to work with. One of the aspects he played with was how sound was produced on timpani. Timpani sticks with heads of hard or soft material (felt, flannel, leather, wood, for example) are all used. In addition, composers may call for other techniques. Holst’s one-act opera The Perfect Fool (1918–22) called for alternating a felt and wooden mallet for the timpani.

Timpani sticks

In Kraft’s Concerto, the timpani is given an unusual sonority ‘created by playing with the hands while wearing leather driving gloves with felt or moleskin patches glued to their fingertips’. In the first movement, the sound starts ‘with felt-covered fingers, the timpanist moves to leather, then to the whole gloved hand, and then to sticks of increasingly hard coverings, until we have reached uncovered wood.’ The second movement, dedicated to his late mother, is based on glissandi, only possible with a Dresden foot pedal.

William Kraft: Timpani Concerto No. 1 – I. Allegretto (Thomas Akins, timpani; Alabama Symphony Orchestra; Parry Karp, cond.)

On the far end of the timpani, we have James Olivero’s Dynasty (2011), a concerto for double timpani. Commissioned by Mark and Paul Yancich, this concerto calls for each timpanist to play 5 drums. The brothers, one a timpanist for the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the other with the Cleveland Orchestra, wanted a work that would show off the capabilities of the timpani as a solo instrument.

Mark (left) and Paul (right) performing with the Atlantic Symphony Orchestra.

James Oliverio: Double Timpani Concerto, “Dynasty” – I. Impetuous (Mark Yancich and Paul Yancich, timpani; Atlanta Symphony Orchestra; Robert Spano, cond.)

From an instrument to accompany military bands to its inclusion in orchestras starting in the 18th century, the timpani, with the help of the improvement in tuning technology, went from being a regular tuned percussion instrument to being an instrument of melodic possibilities.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

**Comment:**

Maureen, your comprehensive exploration of the timpani’s evolution and usage in classical music is truly fascinating!

The way you’ve traced its development from military accompaniment to orchestral prominence, and the diverse ways composers have utilized its unique capabilities,

is a testament to your deep understanding of the subject.

The inclusion of various musical examples

also makes the article engaging and informative. Well done!