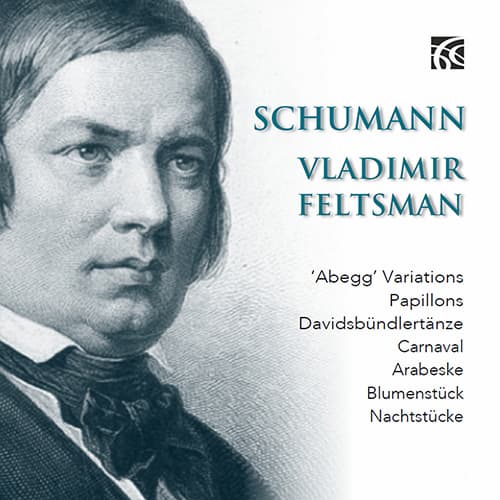

A composer’s first published works are often interesting discoveries: what did they want to publish with their name on it? How did they want to attract attention? In this new recording by Vladimir Feltsman, we get to explore the first published works of Robert Schumann and ask these same questions.

The new Nimbus recording (NI 6433) looks at the first masterworks, from Opus 1 (Abegg Variations) of 1830 through to the Nachstücke (Op. 23) of 1839. For the observant analyst at the time, aside from the works being inspired by poetry and literature, we also see the declaration of Schumann’s split personality and his creation of coded references.

This recording includes Opp. 1, 2, 6, 9, 18, 19, and 23, skipping 3 piano sonatas, the Kinderszenen and Novelletten, among other works.

Robert Schumann, 1830

The Op. 1 Abegg Variations are dedicated to the wholly invented ‘Countess Pauline von Abegg’, based on the very much alive pianist Meta Abegg (1810–1834). The choice of the name gave Schumann the opportunity to turn ‘Abegg’ into the music cell of A–B-flat–E–G–G and so he was ready to create his variation set.

Robert Schumann: Theme and Variations on the name Abegg, Op. 1 – Variation 5: Finale alla Fantasia (Vladimir Feltsman, piano)

Papillons, published in 1831, shows considerable advancement on the Op. 2. Every section of the 11-part work seems to stand alone, each with its own character, texture, and expression. This is where Schumann’s complexity and unconventionality make their first appearance.

The Davidsbündlertänze (“Dances of the League of David”), Op. 6, gives us Schumann’s personality split between Florestan and Eusebius (or Florestan the wild and Eusebius the mild, as he wrote in his diary). Everyone in his circle was assigned a character, with his teacher, Frederick Wieck as ‘Meister Raro’, with a personality that falls between the extremes of Florestan and Eusebius. After publishing the work in 1837, Schumann revised it in 1850, removing the descriptions he’d added to the 18 pieces.

Kriehuber: Robert Schumann, 1839

(Vienna, Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde)

Carnaval (Carnival), Op. 9, is Schumann at the masked balls in the festive season preceding Lent. The music is based on the name of the town ‘Asch’ (A–E-flat–C–B-natural) or (A-flat–C–B-natural) or twisted around as ‘Scha’ (E-flat– C–B– A). The 21 pieces all contain variants on these sequences in music that is filled with riddles. Just as in the masked balls, it’s up to the participants to decipher what’s behind the mask. His final joke is in No. 21, Marche des Davidsbundler contre les Philistins, where this soi-disant march is actually in triple metre.

Robert Schumann: Carnaval, Op. 9: No. 21. Marche des Davidsbundler contre les Philistins (Vladimir Feltsman, piano)

The Arabeske, Op. 18, and Blumenstück, Op. 19, were pieces written while he was separated from Clara Schumann and can be regarded as intimate love letters.

The final work on the recording, Nachtstücke (Night Pieces), Op. 23, was written when Schumann heard of his older brother’s fatal illness. The original title was a bit too macabre (Leichenphantasie or Corpse Fantasy) and Clara persuaded him into the more neutral ‘night’ title.

Robert Schumann: Nachtstücke, Op. 23 – No. 1. Mehr langsam, oft zurückhaltend (Trauerzug) (Vladimir Feltsman, piano)

Vladimir Feltsman

Feltsman’s performance, recorded in 2014 and 2017, lets us range over the extraordinary first pieces by Schumann. His skill in bringing out both the beauty and deliberate awkwardness of Schumann’s compositions is realized throughout. Schumann’s complex personality, which alternately revealed and hid too much, comes through in the music that sounds simple but that can be devilishly difficult to achieve – the technical challenge is making the simplicity come through. This Feltsman achieves in a way that makes it all seem so clear.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter