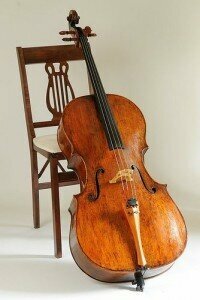

I’d never had one…until today. A dense, dark grey ball the size of a quarter, rolling around inside my cello. I had been practicing the Spanish piece by Gaspar Cassadó Requiebros full of passion and fervor. While wailing on the A string, the highest string, I found myself scraping the fingerboard. What an ugly sound! The weather had turned cold and dry, and my bridge—the carefully carved wooden support, which holds the strings up and transfers the vibrations of the strings to the top of the instrument—was much too low. Time to take my cello in for the usual bridge swap. Most cellists require two cello bridges—one for summer and one for winter, as the dryness or the heat and humidity will make bridge expand (in summer) and contract (in winter.) The difference, although measured in millimeters, makes a huge change to the sound of the instrument, as well as the cellist’s left-hand exertion when pressing the strings down.

I’d never had one…until today. A dense, dark grey ball the size of a quarter, rolling around inside my cello. I had been practicing the Spanish piece by Gaspar Cassadó Requiebros full of passion and fervor. While wailing on the A string, the highest string, I found myself scraping the fingerboard. What an ugly sound! The weather had turned cold and dry, and my bridge—the carefully carved wooden support, which holds the strings up and transfers the vibrations of the strings to the top of the instrument—was much too low. Time to take my cello in for the usual bridge swap. Most cellists require two cello bridges—one for summer and one for winter, as the dryness or the heat and humidity will make bridge expand (in summer) and contract (in winter.) The difference, although measured in millimeters, makes a huge change to the sound of the instrument, as well as the cellist’s left-hand exertion when pressing the strings down.

Gaspar Cassadó: Requiebros (Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi)

dust bunny

My luthier went to fetch a specific tool. I cringed when he presented me with the wooly pellet. Noticing my chagrin, he said, “You can’t imagine the compositions of some of the dust bunnies I’ve seen. I’ve found confetti (for musicians who play weddings) and fake snow, (for musicians who perform The Nutcracker) dust, rosin, and even cobwebs. Artificial fog, stage mist and smoke can leave a residue from the aerosolized particles of mineral oil that linger in the air (for musicians who perform operas, such as Wagner’s Die Walkure or musicals such as Phantom of the Opera, where onstage fog is an essential effect). “To generate sound,” he said, “the vibrations of sound waves move the belly of the instrument, which pumps in and out, transferring the air. The scintilla is sucked in there. In fact, I know of an instrument maker who tries to make his instruments look old. He collects dust bunnies—has a jar of them—and he makes certain to put one into his newly made instruments!”

Wagner’s Die Walkure final scene – lots of fog!

As he put my very own dust bunny in a small bag as a souvenir, I asked if my bow was ready. A string instrumentalist has to have the bow hair replaced periodically, depending on how much playing they do, but at least every few months. The hair comes from the tails of horses, horses that reside in cold climates, as they develop coarse, thick tails. One-hundred and fifty to two-hundred white hairs are used for upper string bows. Sometimes black hair, which is even more gritty, is used for double bass bows. Bow hair will often break during use and can stretch and lose its grip. Talk about a bad hair day!

bow and hair

When the luthier handed my bow to me he laughed and said, “No bow bugs!” I cringed again feeling ill-informed. What are bow bugs? These tiny mites in the larval stage, which eat wool also love to munch on horsehair. Dermestids, a member of the Dermestidae beetle family metamorphoses into worms that shed their skin in their adult stage. If a bow has been sitting in a case unused for months or years, away from the light, you may notice a lot of loose, broken hair or even a cut in a line along the width of the hair. To rid yourself of these mites you must get a rehair and ventilate the bow case, leaving it open to bright light and air.

Active players rarely get bow bugs but don’t be embarrassed. Some violin shops see evidence of bow bugs nearly every day in their shops. If you must store a bow for any length of time do not store it in a closed bow case. Find a safe place like a shelf out of direct sunlight to leave your bow.

It’s very important not to tighten a bow too much and to loosen it after every practice session. The springiness of a bow is important for certain repertoire and if the bowhair is too tight the bow will not bounce. I often would actually loosen my bow for pieces with fast spiccato passages—a bouncing bow stroke—like the quick movement in the Elgar Cello Concerto.

Edward Elgar: Cello Concerto in E Minor, Op. 85 – II. Lento – Allegro molto with spiccato (Jacqueline du Pré)

Packing up my cello and bow, I left the luthier marveling at the things I learned. When I got home I placed my first dust bunny in a special place in my studio. Actually, I think I do see a few dog hairs.

Dear Janet Horvath, I always look forward to your writing in Interlude. It is always interesting, and informative. I have experienced the dust bunny in the instrument, and also, have had a bad experience with bow bugs on a seldom used bow that I left in my case. Imagine the surprise when you open the case one morning and all of the hair is lying about off of the bow at the frog :((

Then there’s cigarette and cigar #HarveryShapiro ash.

When I saw this headine I thought “Some brass player hasn’t been practicing enough!” Thank heavens it wasn’t that!