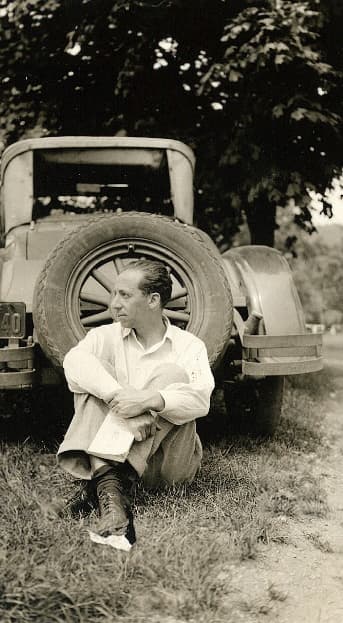

The American poet Hart Crane committed suicide en route from Mexico to New York by uttering a brief ‘Goodbye, everybody!’ and jumping overboard from the steamship Orizaba. His body was not recovered. He was only 32 years old.

Hart Crane

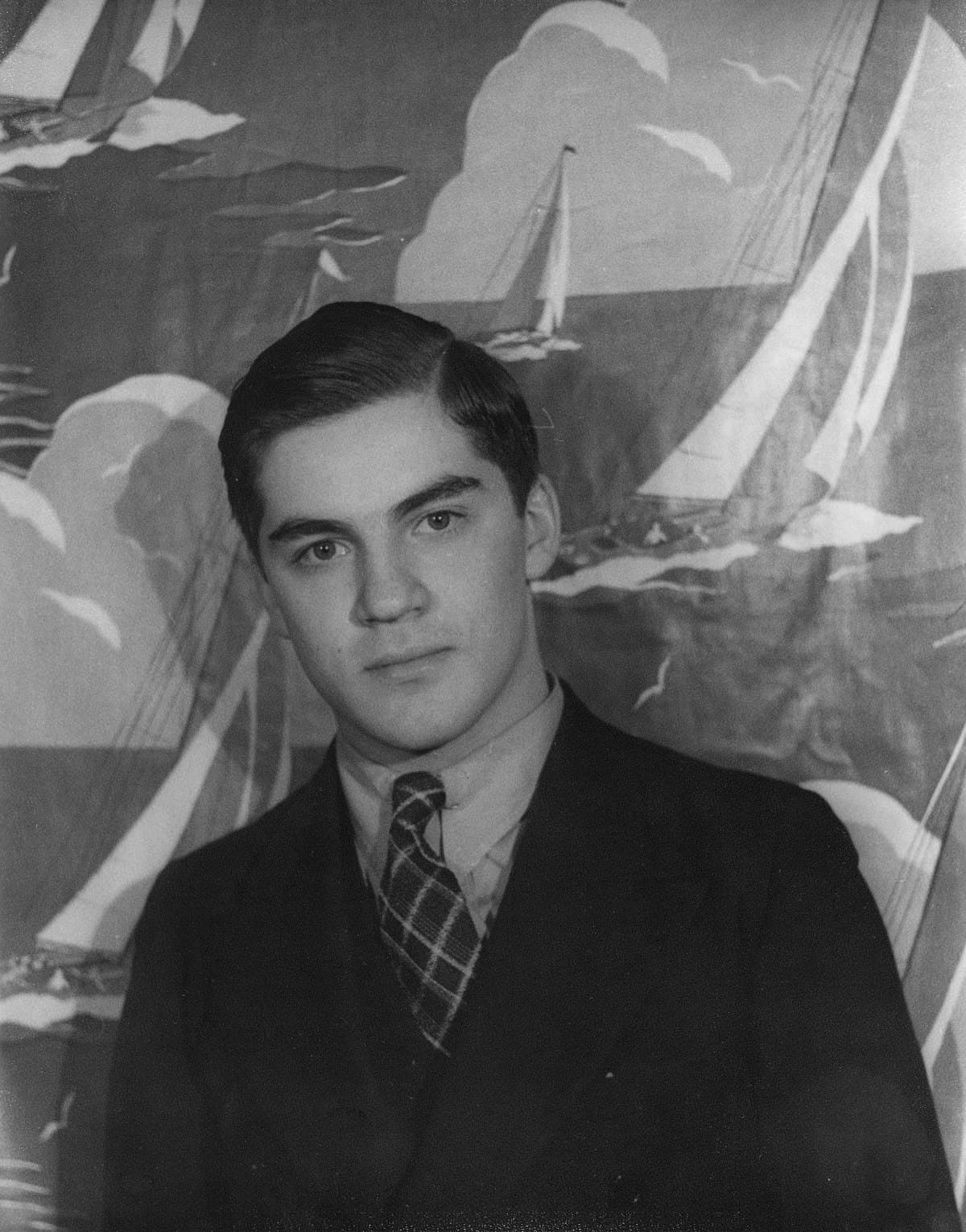

At the time, Aaron Copland was in Mexico at the behest of composer Carlos Chávez, both to explore the musical life of the country and to visit a socialist country. Inspired partly by the news of Crane’s death, Copland wrote Elegies, a duet for violin and viola. It was performed as a commissioned work for the 10th-anniversary concert of the New York League of Composers, played by husband-and-wife performers Ivor and Charlotte Karman.

Aaron Copland, 1932

The piece contains two elegies, not your typical funerary music, but more like a ‘stern, acerbic, tight-lipped proclamation’. The two elegies are heard back-to-back, with no pause between. The second has a slightly lighter mood and texture, but this doesn’t last very long. It’s pure Copland, yet without sounding like anything that’s familiar to us.

Aaron Copland: Elegies (Natalie Rose Kress, violin; Danny Kim, viola)

Following the premiere, Copland revised the work, removing the first section and rewriting it as the fourth part of his work Statements (1935).

After this, he withdrew Elegies from his catalogue.

This work, made up of 6 ‘statements’: Militant, Cryptic, Dogmatic, Subjective, Jingo, and Prophetic, was another commission from the New York League of Composers. The last two movements were given their premiere in 1936, and the full work was finally performed in 1942, with Dimitri Mitropoulos leading the New York Philharmonic. Copland’s notes to the piece begin with a definition: ‘The title Statement was chosen to indicate a short, terse, orchestral movement of a well-defined character, lasting about three minutes. The separate movements were given suggestive titles as an aid to the public in understanding what the composer had in mind when writing these pieces.’

Each movement has a different orchestration, and he has transformed the duo from Elegies into a movement for strings alone, without the double basses. Other movements are for winds and strings, or winds alone, or for full orchestra.

Aaron Copland: Statements – IV. Subjective (London Symphony Orchestra; Aaron Copland, cond.)

In 1946, however, he reused a passage from near the close of the second elegy in the slow movement of his Symphony No. 3. Copland’s third symphony is notable for how the final movement begins. There’s no pause at the end of the third movement, it flows directly into a quote from one of Copland’s best-known pieces, The Fanfare for the Common Man.

Aaron Copland: Symphony No. 3 – III. Andantino quasi allegretto— (Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Aaron Copland: Symphony No. 3 – IV. Molto deliberato (freely, at first) (Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

The feelings in each of the works: Elegies, Statements: IV. Subjective, and the third movement of the symphony seem to all carry a delicate structure. He’s not making strong statements; he’s whispering around the edges. Crane suffered all his life from his sexuality, being homosexual in a world where it was illegal. On the Orizaba, he was beaten up by a crew member after making sexual advances and on 27 April 1932, ended his life when he jumped overboard.

Aaron Copland had his male companion, the photographer Victor Kraft, starting in 1932. Copland didn’t speak about his private life but was ‘one of the first prominent homosexual composers to co-habit with a romantic partner.’

Carl Van Vechten: Victor Kraft, 1935

Copland also had an affinity for Crane’s poetry, with The Bridge, Crane’s long poem inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge, being Copland’s inspiration for his ballet Appalachian Spring. Copland said in his autobiography that ‘it was Crane’s American epic The Bridge with its mixture of nationalism, pantheism, and symbolism’ that was the basis for the story of Appalachian Spring.

Copland’s Elegies for Hart Crane, after their first performance, were used as the basis for other works, but he never changed the essential character of the original work. We might want to think carefully about the second elegy’s position in his Symphony No. 3, where it’s followed by the 1942 Fanfare for the Common Man. Who is the common man now?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter