Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart © Seth / The New Yorker

Composers use a variety of means to create drama in music, from simple devices such as dynamics (level of sound) or tempo (speed) to repetitions, the use of rests and pauses, and changes of harmony or key (modulation).

Mozart’s Fantasy in D minor for solo piano is a wonderful example of the use of specific devices to create a work of great drama and emotional depth, making it an incredibly rewarding piece to play or hear. I first encountered it when I was about 11 years old, and have continued to enjoy playing it ever since.

Composed in c1782, the Fantasy was only published after Mozart’s death and was unfinished, ending on the fermata (pause) at bar 97. When the Breitkopf & Hartel edition appeared some years later, the fantasy included an ending, presumably composed by an editor, and this version is the one which appears most commonly in subsequent publications and performances. Mitsuko Uchida is probably the only pianist who offers an alternative ending to the Fantasy, by reiterating the opening section.

D minor was Mozart’s favourite “tragic” key, and it is the key of some of his darkest, most profound music, including his Requiem.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Fantasia in D Minor, K. 397 (Seong-Jin Cho, piano)

Mozart: D minor Fantasy K397

Dynamics, repeated patterns & changes in harmony

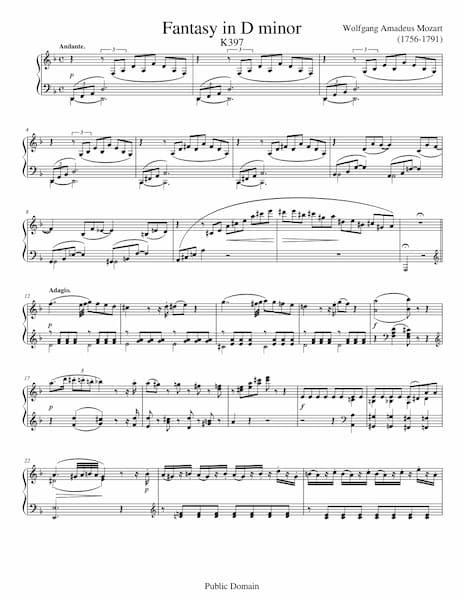

Opening section (bars 1-11)

Mozart creates a sense of mystery and tension from the outset through the use of a repeated broken chord pattern over sustained, low bass notes within a quiet dynamic range. The subtle shift in harmony sets up a sense of expectation but the section ends with a broken chord figure in the Dominant harmony which creates great tension: the music is not at rest and we are left waiting, wondering what comes next. The low A in the bass exaggerates the tension.

‘Sighing’ slurs and ‘breathless’ rests

First main theme (bars 12-54)

A mournful melody is introduced at bar 12, punctuated by “sighing” slurs and rests which emphasise the tense, unsettled nature of the music. Stark contrasts in dynamics lend greater dramatic weight (e.g. bars 16, and 20-22). At bar 23 a new motif is introduced which uses slurs, staccato and rests to create a sense of almost breathless agitation in the music. Once again, Mozart uses a fermata at the end of this section which gives no clue of what comes next…

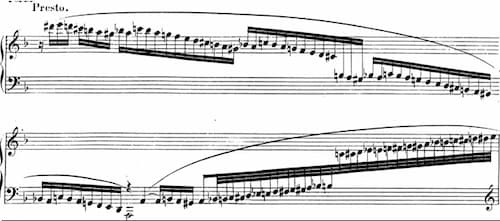

Tempo, scale and arpeggio patterns, and chromaticism

Cadenza passages – bars 34, 44 & 53

These three cadenza-like passages are scored without bar lines, suggesting they should be played free form and with an improvisatory character. They are some of the most dramatic and exciting sections in the piece, their drama enhanced through the use of rapidly descending and ascending scales, chromaticism and diminished chord arpeggios.

D minor Fantasy K397 Cadenza

A modulation and a dramatic change of mood

Bars 55-end

The final part of the Fantasy is scored in D major (often regarded as Mozart’s “happy” key). The dominant chord and fermata at bar 54 set us up for the new section: because the harmony is not immediately resolved, when the D-major section begins, there is a much greater sense of delayed gratification. Additionally, the very cheerful major key brings an uplifting lightness to the music after the tragic darkness of what has gone before. The piece ends very positively with four chords marked fortissimo.

In Mitsuko Uchida’s version of the Fantasy, the mournful key of D minor is reintroduced after bar 97 by the repeat of the opening section, and darkness and mystery infuse the music once again.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Fantasia in D Minor, K. 397 (Mitsuko Uchida, piano)