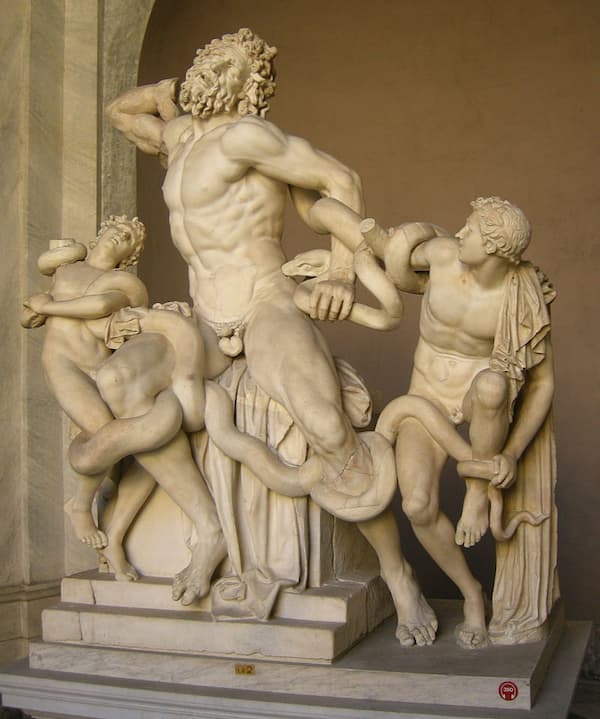

Let’s imagine that an archaeological dig unearths a precious statue from antiquity. Sadly, however, the sculpture is incomplete and missing arms and limbs. Such was the case in the early 16th century, and soon, a competition got underway to reconstruct the missing arms. At the head of the reconstruction committee was no other than the famed architect and painter known as Raphael.

Laocoön and his sons, also known as the Laocoön Group

The result of the reconstruction was judged to have been true to the work of the original artist. But there was a problem. When the original arm was discovered several centuries later, it looked nothing like the reconstruction.

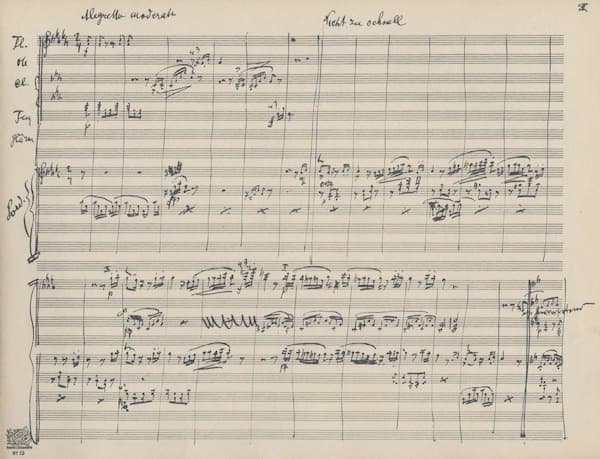

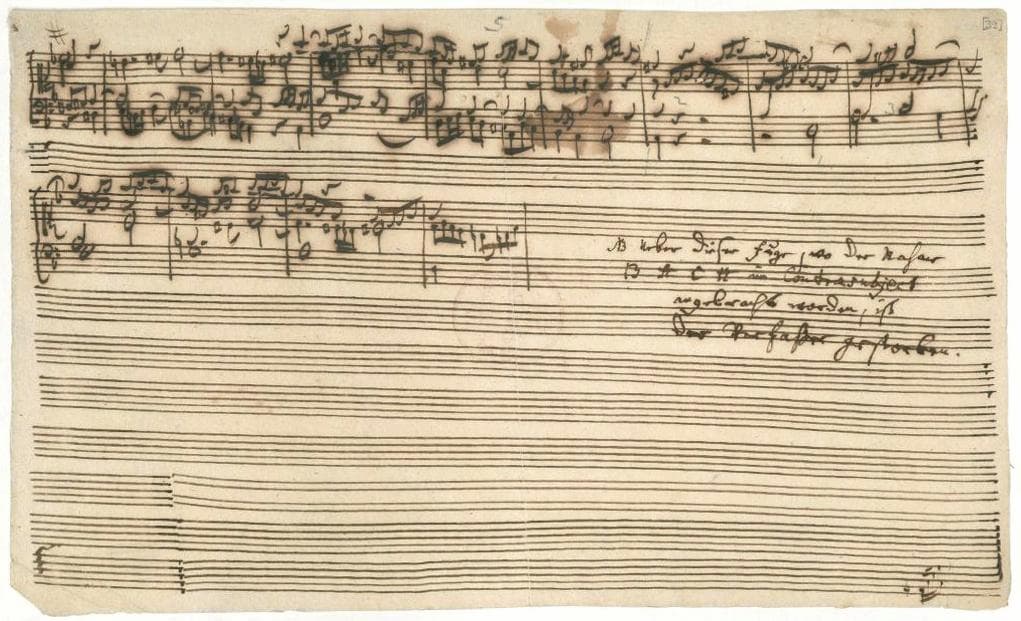

The musical work of art relies on the realisation of its content through actual performance, and it functions slightly differently from other works of art. However, a rather substantial number of musical works have also remained incomplete for a host of possible reasons. Some works were abandoned as unworthy; others were put aside to be completed later. And on occasion, disease or death brutally intervened. Depending on the degree of completeness, a good many have been finished and or reconstructed. So we decided to canvas some of these unfinished compositions, starting with Bach’s famous Art of the Fugue.

J.S. Bach: Art of Fugue

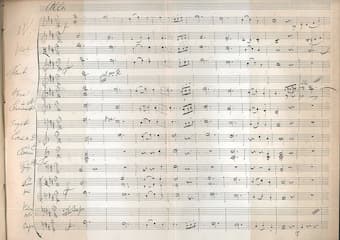

Bach’s unfinished fugue

J.S. Bach: Art of Fugue “Fuga a 3 Soggetti” (Konstantin Lifschitz, piano)

This celebrated collection of contrapuntal movements remained unfinished, as Bach apparently died while incorporating his musical signature. The unfinished fugue on “3 Subjects” breaks off abruptly with a note by C.P.E Bach explaining that his father had died during composition. That story is not really plausible as Bach was already blinded by two botched eye operations and unable to work, but a substantial number of musicians and musicologists have attempted a completion. An equal number of performers—like on the featured track—terminate their interpretation with the last written note on the manuscript page. Even with all the expertise in the world, can we ever successfully append a “musical arm?” Of course we can, as long as we have the clear understanding that it at best creatively parallels the possible intentions of the composer.

Puccini: Turandot

One famous example reaches us from the world of opera. When Arturo Toscanini raised his arms at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan on 25 April 1926, he was getting ready for the premiere of an unfinished opera. Turandot, the operatic adaptation of an originally 12th-century Persian epic filtered through readings by Friedrich Schiller and Carlo Gozzi, had been incomplete at the time of Puccini’s death in 1924. The composer left 36 pages of notes and musical sketches for the finale of Turandot with Toscanini and begged him, “don’t let my Turandot die.”

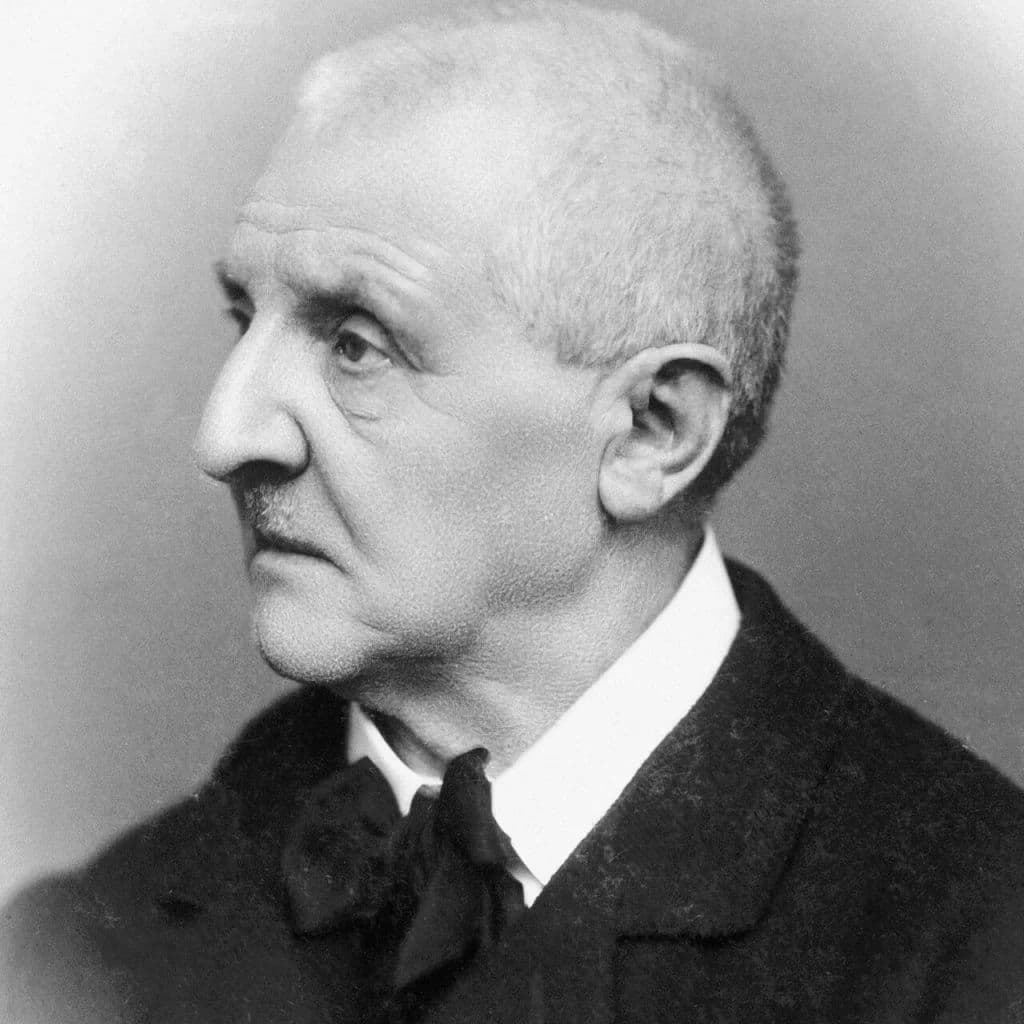

Franco Alfano

Franco Alfano was called upon to finish the score, but during the premiere on 25 April 1926, Toscanini stopped the performance in the third act, exactly on the last note of Puccini’s score. He turned to the audience, put down his baton and said, “Here, the performance finishes because, at this point, the maestro died.” The first performance of the opera, as completed by Alfano, took place the following evening, and his “musical arm” has been officially accepted as an authorised completion.

Schubert: Symphony No 8 B minor Unfinished

One of the biggest and most exciting mysteries in classical music is the question of why Franz Schubert never completed his “Unfinished Symphony.” We do know that the Music Society in Graz bestowed upon Franz Schubert an honorary diploma in 1823. To thank the Society, Schubert sent his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner, a leading member of that organisation, an orchestral score he had written in 1822. It consisted of two complete symphonic movements and the first two pages of the start of a Scherzo. The rest of the Scherzo was discovered after Schubert’s death, but the final movement has never been found.

Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 in B minor

Since Schubert lived for several more years after leaving that work behind, it has been suggested, among various other theories, that Schubert stopped work in the middle of the Scherzo because he associated it with his initial outbreak of syphilis and that he recycled the final movement in his incidental music for Rosamunde. We will probably never know for sure, but on the 100th anniversary of Schubert’s death in 1928, Columbia Records held a worldwide competition for the best completion of the “Unfinished,” and about 100 completions were submitted. The “Schubert Mystery” is alive and well and continues to inspire various theories and attempts at completion.

Mozart: Concerto for violin, piano and orchestra in D major

In 1778, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart visited Mannheim in search of an official appointment. For an upcoming concert, the “Academie des Amateurs,” he started composing a concerto for violin, piano and orchestra. Mozart indicated to his father that he himself would play the piano part, and the concertmaster of the Mannheim orchestra, Ignaz Fränzl, was to play the solo violin part. Mozart wrote the first 120 measures of the first movement, with only the first 74 measures completely scored. Maybe Mozart lost hope of having his concerto performed, and as his father ordered him back to Salzburg, he never continued to work on the composition. The extended Mozart fragment has been considered “of great quality… containing passages at its vibrant best.” When the composer Philip Wilby looked at the fragment, he noticed its similarity to the Sonata for violin and piano K. 306. As such, he came to the conclusion that the sonata was a revised version of Mozart’s unfinished concert, and he reconstructed all three concerto movements as such. It’s a case of the Mozart fragment completed with existing and published material by Mozart himself. Although borrowed from a different context and genre, the result is nevertheless charming indeed.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter