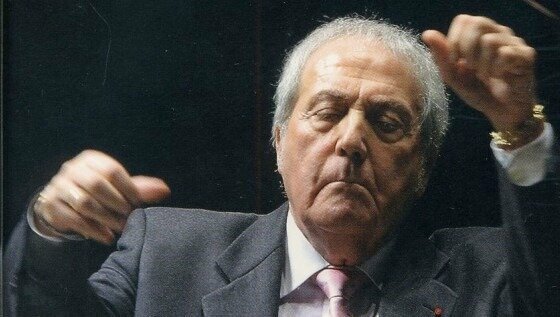

Aldo Ciccolini

Credit: http://www.crushsite.it/

The waltz was one of several similar dances that came out of southern Germany, Bavaria and Austria that had two common features: they were in triple time and were danced by couples in closed embrace. The Waltz hit England by 1791 and already by 1797, its popularity was being fought. Opponents had two objections: one medical in that the speed at which dancers whirled around the room must be bad for them and one moral because of the closeness with which the dancers held each other. One commentator even noted the salacious activities that occurred in the darker corners of the room. In England, this dangerous dance from deepest Europe was regarded by parents as bad for morals and by their daughters as a wonderful new dance.

Not to be left out in the mad whirl, the salon was the next to claim the waltz for itself. Mozart’s student Hummel was one of the earliest of the piano virtuosos to take on the dance and Schubert was quickly behind him in creating pieces published as Walzer. The waltz quickly went around Europe, visited the Russian composers Glinka, Tchaikovsky, and Glazunov, and then moved over to France where composers such as Ravel make it clear that the waltz is a thing of the past. The waltz was next taken up by composers of light music, where it remains today as just a memory of its dangerous beginnings in the mid-18th century.

In Ciccolini’s new recording, we see the waltz from several perspectives: in the hands of the consummate piano composers such as Chopin and Schubert; in the hands of French modernists such as Chabrier, Debussy, Satie, and Tailleferre; and by the Germano-Nordic track of Brahms, Grieg, and Sibelius. There are easy dances by Chabrier matched with the ultimate in difficulty of Fauré’s Valse-Caprice, Op. 59 and Gabriel Pierné’s Viennoise suite, arranged here for piano.

In Ciccolini’s new recording, we see the waltz from several perspectives: in the hands of the consummate piano composers such as Chopin and Schubert; in the hands of French modernists such as Chabrier, Debussy, Satie, and Tailleferre; and by the Germano-Nordic track of Brahms, Grieg, and Sibelius. There are easy dances by Chabrier matched with the ultimate in difficulty of Fauré’s Valse-Caprice, Op. 59 and Gabriel Pierné’s Viennoise suite, arranged here for piano. Tailleferre: 2 Pieces: No. 2. Valse lente

Pierné: Viennoise

Album cover

Credit: http://www.naxosmusiclibrary.com/

Sibelius: Valse triste, Op. 44, No. 1

It’s a lovely album that takes an overview of the world of the waltz and, oh so slowly, dances us into the dark corners and into the shadows of a dance that once ruled the world.

Official Website