Charles Ives’ wonderfully named Calcium Light Night started its life as a piece for piccolo, clarinet, cornet, trombone, bass drum, and four pianists on two pianos. It depicts traditional fraternity parades on the campus of Yale University, which Ives attended from 1894 to 1898. Members wishing to join the fraternity are chosen on Tap Night and then parade around the university, singing the songs of their fraternity, illuminated by a ‘calcium light’, a very bright light used in theatres.

Charles Ives, graduation photo, 1898, Yale University

Ives caught the moment during the evening when the various fraternities would cross paths. One description of the work has one group singing the songs of Ives’ fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon (‘A band of brothers in D.K.E., we march along tonight’) intermingling with the songs of their rival fraternity, Psi Upsilon (And again we sing thy praises, Psi U., Psi U.!). Another writer hears that each of the wind instruments (piccolo, clarinet, cornet, and trombone) plays music from 4 separate fraternities, with the piano supplying support. The parade starts at a distance, passes the listener, and disappears into the night.

Charles Ives: Set No. 1 for Chamber Orchestra – V. Calcium Light Night (ed. K. Singleton) (Orchestra New England; James Sinclair, cond.)

In this picture from 1910, we can see the Yale marchers and their calcium light on the tripod behind them.

Calcium Light Night, 1910 (Yale University Archives)

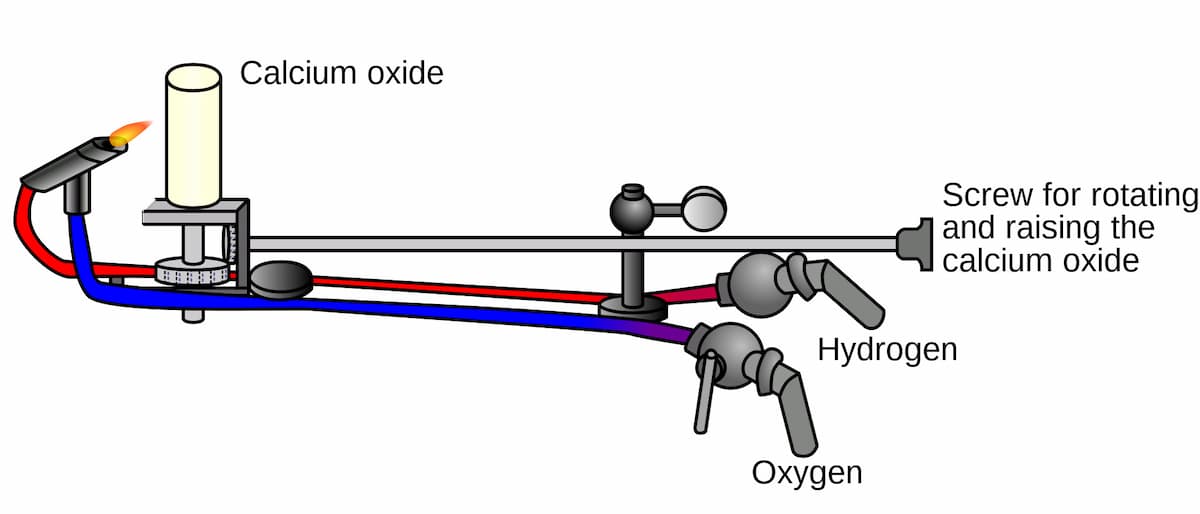

The calcium light was created in the 1820s. The mechanism consists of a flame fed on hydrogen and oxygen directed on a cylinder of calcium oxide, also known as quicklime, creating a very bright light. It was used on theatre stages until the invention of electrical lighting – the idea of a calcium light survives in the phrase of someone being in the ‘limelight’, i.e., a calcium light. By the 1830s, limelights were used in theatres, first in England and then around the world by the 1860s and 1870s.

Theresa Knott: Limelight diagram

In this 19th-century limelight from the city theatre in Bruges, Belgium, you can see the two pipes for the two gasses, the adjustment knob, and, on the front of the box, a place to put coloured filters (green, red, yellow, purple, and blue).

Beireke1: 19th century limelight (Stadsschouwburg, Bruges, Belgium)

Ives’ ability to catch the cacophony of the everyday world was unmatched. In a piece such as Central Park in the Dark (another work with a musical title), we start in the darkness of Central Park and hear the music spilling out of the doorways on Broadway, a runaway horse, an elevated train, and life in the light.

Charles Ives: Central Park in the Dark (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

A night procession around Yale, a night in Central Park, and the light of sound all come together in these sound pictures of lost times.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter