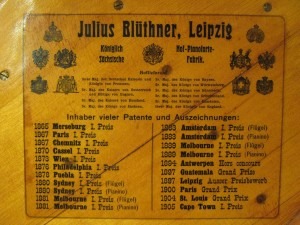

What do Queen Victoria, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, Tsar Nicholas II, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and numerous others have in common? They all purchased and played instruments produced by the Leipzig piano manufacturer Blüthner. Around 1900, Blüthner was the largest piano maker in Germany, with almost 5,000 instruments produced annually. Together with Bechstein, Bösendorfer and Steinway & Sons, Blüthner was referred to as one of the “Big Four” piano manufacturers. And they were certainly not lacking celebrity endorsements, as Sergei Rachmaninoff famously commented “There are only two things which I took with me on my way to America… my wife and my precious Blüthner.”

What do Queen Victoria, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, Tsar Nicholas II, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and numerous others have in common? They all purchased and played instruments produced by the Leipzig piano manufacturer Blüthner. Around 1900, Blüthner was the largest piano maker in Germany, with almost 5,000 instruments produced annually. Together with Bechstein, Bösendorfer and Steinway & Sons, Blüthner was referred to as one of the “Big Four” piano manufacturers. And they were certainly not lacking celebrity endorsements, as Sergei Rachmaninoff famously commented “There are only two things which I took with me on my way to America… my wife and my precious Blüthner.”

The instrument was the brainchild of Julius Blüthner, who initially trained as a cabinet-maker before attempting to set up a workshop in Leipzig. Since Blüthner had been born in a different part of Saxony, it took him a long while to gain Leipzig citizenship. However, by 1853 he had all documents in place and together with three other craftsmen started to build his dream.

The instrument was the brainchild of Julius Blüthner, who initially trained as a cabinet-maker before attempting to set up a workshop in Leipzig. Since Blüthner had been born in a different part of Saxony, it took him a long while to gain Leipzig citizenship. However, by 1853 he had all documents in place and together with three other craftsmen started to build his dream.

Only one short year later, Blüthner exhibited his pianos at the Leipzig Industrial Exhibition in 1854 and scored a resounding success. In fact, he managed to sign up the Leipzig Conservatory of Music as a customer for his instruments. Praised for its expert craftsmanship and ornate cases decorated with veneer, mother of pearl and gold leaves, Blüthner pianos were in high demand. As such, it was no surprise that the Blüthner factory had 136 workers on its payroll in 1864.

Only one short year later, Blüthner exhibited his pianos at the Leipzig Industrial Exhibition in 1854 and scored a resounding success. In fact, he managed to sign up the Leipzig Conservatory of Music as a customer for his instruments. Praised for its expert craftsmanship and ornate cases decorated with veneer, mother of pearl and gold leaves, Blüthner pianos were in high demand. As such, it was no surprise that the Blüthner factory had 136 workers on its payroll in 1864.

Constantly pushing innovation, Blüthner patented the “Aliquot system” of system of stringing which involved a non-struck fourth string in the treble section. This fourth string is stimulated to vibrate through sympathetic resonance when the other three strings are struck, resulting in an acoustical system enriching the overtone series. It produces a lively and resonant treble, which is audible over a wide range. The sympathetic string is tuned in unison, and it significantly contributed to the instrument’s reputation of producing a “golden tone.” Other innovations included a cylindrical soundboard, hammers cut at an angle, and the patented “Blüthner action” was regarded as being the finest of all time! No wonder, Debussy, Bruckner, Mahler, Prokofiev and Shostakovich absolutely adored the instrument!

Constantly pushing innovation, Blüthner patented the “Aliquot system” of system of stringing which involved a non-struck fourth string in the treble section. This fourth string is stimulated to vibrate through sympathetic resonance when the other three strings are struck, resulting in an acoustical system enriching the overtone series. It produces a lively and resonant treble, which is audible over a wide range. The sympathetic string is tuned in unison, and it significantly contributed to the instrument’s reputation of producing a “golden tone.” Other innovations included a cylindrical soundboard, hammers cut at an angle, and the patented “Blüthner action” was regarded as being the finest of all time! No wonder, Debussy, Bruckner, Mahler, Prokofiev and Shostakovich absolutely adored the instrument!

Around the turn of the 20th century, Blüthner added a series of upright models to his inventory, but advances in technology made the “Blüthner action” less desirable. When Julius Blüthner died in 1910, his sons Max, Robert and Bruno took over the business and managed to secure an imperial and royal warrant of appointment to the court of Austro-Hungary. However, demand gradually declined and during WWII the factory was completely destroyed.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Blüthner added a series of upright models to his inventory, but advances in technology made the “Blüthner action” less desirable. When Julius Blüthner died in 1910, his sons Max, Robert and Bruno took over the business and managed to secure an imperial and royal warrant of appointment to the court of Austro-Hungary. However, demand gradually declined and during WWII the factory was completely destroyed.

With help from the East German government, the company rebuilded and was eventually nationalized, although it remained under Blüthner management. Since 1994, Blüthner pianos are being imported in the USA, and the “Haessler” and “Irmler” brands have been added. In 2009, Blüthner purchased the “Ronisch brand”—originally founded by Carl Ronisch in Dresden in 1845—and they continue to push innovation. For one, the South African artist Gabriel Meiring has painted the lids of a number of handcrafted Blüthner concert grands, and the stunning “Ariana Crystal Grande” was used for performance at the 2015 Grammy Awards. Mikhail Pletnev writes, “Following countless performances in some of the most prestigious concert halls in the world – I am convinced – Blüthner pianos have an exceptionally beautiful tone. I prefer Blüthner pianos to other instruments.”

With help from the East German government, the company rebuilded and was eventually nationalized, although it remained under Blüthner management. Since 1994, Blüthner pianos are being imported in the USA, and the “Haessler” and “Irmler” brands have been added. In 2009, Blüthner purchased the “Ronisch brand”—originally founded by Carl Ronisch in Dresden in 1845—and they continue to push innovation. For one, the South African artist Gabriel Meiring has painted the lids of a number of handcrafted Blüthner concert grands, and the stunning “Ariana Crystal Grande” was used for performance at the 2015 Grammy Awards. Mikhail Pletnev writes, “Following countless performances in some of the most prestigious concert halls in the world – I am convinced – Blüthner pianos have an exceptionally beautiful tone. I prefer Blüthner pianos to other instruments.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5, Op. 73, “III Rondo”

Anatoly Lyadov: Prelude, Op. 11, No. 1