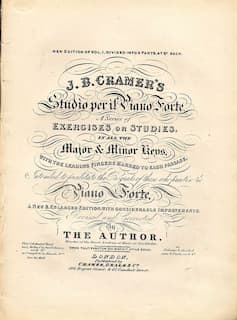

Studio per il pianoforte by Johann Baptist Cramer

The name Johann Baptist Cramer (1771-1858) is essentially synonymous with his celebrated set of 84 studies published as “Studio per il pianoforte.” The first set of 42 studies appeared in print in 1804, and a second set was issued in 1810. Cramer’s teacher Muzio Clementi complained bitterly that Cramer had not only stolen his idea of a comprehensive technical instruction, but that he had taken his title as well. Cramer was part of a group of composers, pedagogues, pianists, publishers and builders who contributed to the development of the piano in London at the turn of the 19th century. Historically known as the “London Pianoforte School,” the city became a great magnet for continental musicians, and many leading developments in piano music were composed and published there. Once Cramer had published his “Studies,” similar efforts rapidly appeared, including sets of studies by Steibelt, Wölfl, and eventually Clementi, who published his Gradus ad Parnassum in 1817.

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1818

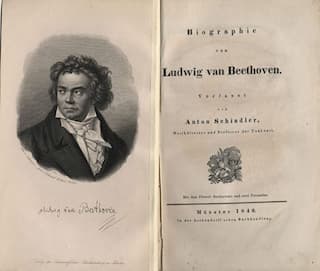

Cramer’s “Studio” was the most widely used and admired collection in the early 19th century, and even Robert Schumann described it “as the finest training for head and hand.” Not to be outdone, Chopin considered them a necessary tool for a pianist, and Ludwig van Beethoven used them to instruct his nephew Carl. Of course, Beethoven knew Cramer personally, and in his Beethoven biography, Anton Schindler writes, “Our master declared that Cramer’s Etudes were the chief basis of all genuine playing. If he had ever carried out his own intention of writing a pianoforte method, the etudes would have formed in it the most important part of the practical examples, for on account in many of them, he looked upon them as the most fitting preparation for his own works.” Schindler is not always the most reliable source, but Beethoven did apparently own a Haslinger edition of Cramer’s studies and entered a number of annotations in 21 studies. That primary source has not survived, but Schindler entered Beethoven’s annotations in another Haslinger edition. On top of each study over the name “Beethoven,” he also entered his own annotations signed “A.S.”

Johann Baptist Cramer

In 1893, the British Beethoven scholar John Shedlock discovered Schindler’s copy of Cramer’s studies in the State Library of Berlin. He translated Beethoven’s annotations into English, quoted Schindler at length, and published it for the first time. Shedlock summarizes, “In one respect, Beethoven regarded the mere notes in the music as an incomplete revelation of the composer’s intentions. But in relation to the Cramer Etudes these declarations are of extreme interest, in their application to Beethoven’s pianoforte works they become of the highest importance … only those who have true feeling of music and who, in addition, have reflected long and carefully on their art ought fully to apply these Beethoven directions to the great composer’s music.” Actually, Beethoven had planned to write a School of Piano Playing, first mentioned in 1818, in order “to protect his works from being mangled in performance.” Sadly, that particular project never materialized.

Beethoven biography by Anton Schindler

Beethoven’s annotations in Cramer’s studies reveal a continual preoccupation with three basic issues: legato, accentuation and the application of poetic feet in the music. As such, these annotations reveal issues that mattered most to the composer in performance, and “provide fresh perspective on his performance intentions.” The use of legato and the prolonged touch, the assignment of “long and shorts to the passagework and the awareness of proper accentuation throw new light on the performance of Beethoven’s own works.” It has rightfully been suggested that his “annotations to Cramer’s studies are one of the most valuable sources of information about performance practice in his works.” Of course, some suspicious minds have discredited these annotations and suggested that Schindler invented the whole thing. Well, deconstruction is one thing, but it does not take away the fact that Cramer was highly valued. In addition, the Beethoven/Schindler explanations do shed specific light on some of the performance practice issues of their time.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter