The Anglo-Irish-French composer Augusta Holmès (1847–1903) was born in Paris, daughter of a wealthy Irish officer and an English mother. Although her parents would have preferred her to have an interest in the plastic arts of drawing and painting, it was music that was her art form. She started her musical studies in 1858, at age 11, but had to study privately. The Paris Conservatoire was closed to her since she didn’t have French citizenship and had English-speaking parents.

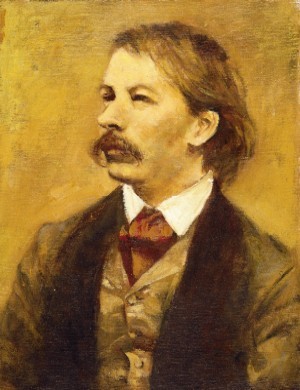

August Holmes, 1908

Holmès studied both piano and organ. With clarinettist Hyacinthe Klosé she expanded into the woodwinds. She also studied voice with Guillot de Sainbris, who had opened a singing school in Paris for theatre artists. In the salons of Paris and Versailles, she met many of the musical composers of the day and particularly impressed César Franck, becoming part of his inner circle in the 1870s. He would go on to become her most important teacher.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, few women were serious orchestral composers – that sphere seemed to be limited exclusively to men – but Augusta started her career with a three-movement symphony based on the medieval story of Orlando Furioso. Her Roland Furieux of 1875–1876 uses Ludovico Ariosto’s story from 1515 as its basis, setting three scenes from the epic poem.

The symphony opens as ‘Paladin Roland rides through the world searching for his unfaithful Angélique’ and it’s full of his galloping horse and his restless searching keeping Angelique’s theme in his head.

Augusta Holmès: Roland Furieux – I. Allegro (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

Although there is a record of one movement from the work being played at the Théatre du Châtelet on 14 January 1877, the first complete performance of the work doesn’t seem to have taken place until 2019 in Wales.

In the musical society of France, as a non-citizen, Augusta was not able to participate in the activities that built a composer in 19th century France: she couldn’t attend the Paris Conservatoire, which meant she couldn’t compete for the Prix de Rome, and she couldn’t contribute to the musical activities of the 1878 World Exhibition. It wasn’t until 1879 that Augusta was granted French citizenship and was given the same rights as French citizens had.

Augusta described herself as a ‘poet-composer’ and wrote extensive prefaces and programme notes for her symphonic works. Some of her symphonic poems carried highly political programs: her symphonic poem Irlande contrasted Ireland’s glorious past (with revelry, feasting, and merriment) with its contemporary problems under its current oppressive English rule. Irish nationalism and the potato famine led to violence and emigration, stripping the country of its citizens. Holmès’ poem opens with a shepherd singing in the hills, depicted with a lonely clarinet. This is soon followed by a lively folk festival and a horn melody. A change of mood signalled by a snare drum and tuba lead to a funeral march for the lost Irish. At the end, percussion and horns summon the ancient heroes of Ireland.

Augusta Holmès: Irelande (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

Another political tone poem was her symphonic poem Pologne, seeming based on the repression of Poland under the Russians. The painting by Tony Robert-Fleury, Warsaw on 8 April 1861, was a visual inspiration for this work, depicting the aftermath of the Russian troops firing on an unarmed crowd in Castle Square.

Tony Robert-Fleury: Warsaw on 8 April 1861, ca. 1866 (National Museum Kraków)

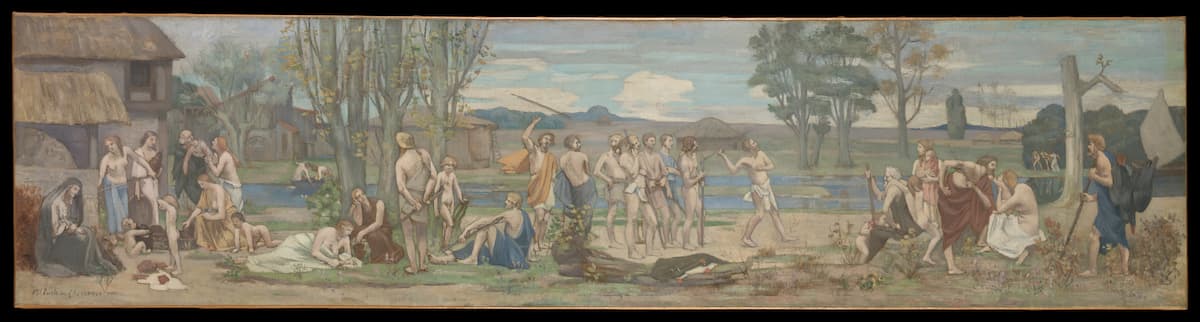

Other symphonic poems by August Holmès included Ludus pro Patria (Play for the Country), based on the painting of the same name by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, depicting athletes training with pikes in ancient France.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes: Ludus pro patria (Patriotic Games), ca. 1883–1889 (New York: Metropolitan Museum)

The copy at the Metropolitan Museum in New York is a reduced size replica of the original 1882 mural that is installed in the Musée de Picardie in Amiens.

One of Augusta’s last symphonic poems looks to Greek mythology and the story of Andromeda. This did receive a premiere in Paris in 1900. The story comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where Perseus, on his way back from slaying the Medusa, sees Andromeda chained to a cliff. Because her mother, Cassiopeia, thought herself more beautiful than any of the sea goddesses, Poseidon took his revenge on her daughter to sacrifice her to a sea monster. Perseus fall in love (of course), defeats the sea monster (of course), and then flees with Andromeda. Holmès wrote a poem for her piece and it closes with ‘Winged poetry and eternal love / lift you away to the eternal gods, away to the stars’, referring to Andromeda’s position as a constellation in the sky.

Titian: Perseus and Andromeda, ca 1554–1556 (The Wallace Collection)

Augusta Holmès: Andromède (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

She defined herself in her will, in terms of her religion and her nationality: ‘I am a Christian, a Catholic, a republican and a patriot. But in my heart, I harbour a love for glorious France and poor Ireland, my two mothers’. Holmés died in 1903, having achieved her dream of placing music by women in the range of great symphonic works by French composers.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter