Professionally, the years 1876 and 1877 accorded Antonín Dvorák (1841-1904) the first glimpses of international recognition. Privately, however, these years were overshadowed by great personal tragedy. Just two days after her birth, Dvorák’s little daughter Josefa unexpectedly died. In response, the devout Catholic Dvorák began to draft a religious cantata on the text of the Roman Catholic hymn Stabat Mater as a means of coping with the loss of his child.

Antonin Dvořák

By mid 1876, Dvorák put the work aside to concentrate on a number of other commissions, but tragically, on 13 August 1877 his 11-month-old daughter Ruzena (Rose) accidentally drank a phosphorus solution and died. Overwhelmed by this new tragedy, Dvorák once more sought solace in the composition of the Stabat Mater. Barely a month later, on 8 September, his 3-year old son Otakar contracted smallpox and after a short feverish struggle, succumbed to the disease. Antonín and his wife Anna were utterly devastated, but Dvorák managed to complete the work on 13 November 1877.

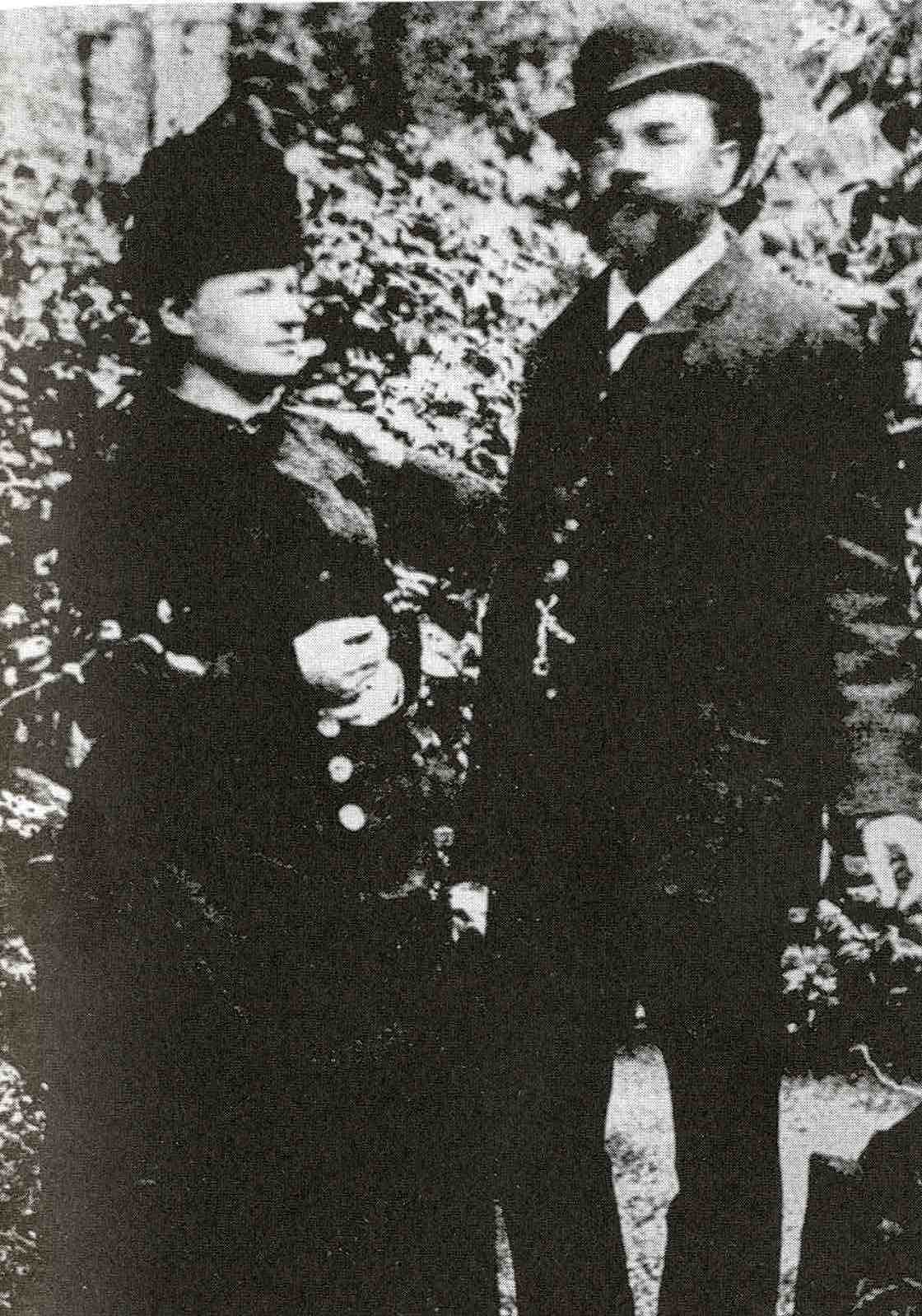

Antonín Dvořák with his wife Anna in London, 1886

Given the enormous personal tragedy and grief, we might expect to hear an outright gloomy composition, filled with despair and hopelessness. But that is not the case, as the Stabat Mater is one of the most powerful declarations of faith in the history of music. For one, the performance setting is not located in the church, but it is supposed to be heard as a concert piece based on a religious text. Unfolding in ten distinct sections of music, the work spans a structural and musical arch, anchored in the opening and closing movements. But it is not simply musical architecture that drives the composition. Rather, the work is propelled forward by the immense melodic and rhythmic energy unleashed in the opening movement. That energy, in a kind of apotheosis, gradually comes to rest only in the concluding movement.

Dvořák: Stabat Mater

The opening movements are by far the longest and emotionally complex in the work. Dvorák set the first four stanzas of the poem for chorus and four soloists, all initiated by an extended orchestral introduction. The undulating repetition of a single note creates a stark and desolate vision, one that is reinforced by a chromatically descending theme of lament. The orchestra builds to a shattering climax, which fades into the entrance of the chorus. Expanding on the orchestral material, the chorus tenderly develops the musical ideas and eventually reaches a terrifying climax on the word “lacrimosa” (tears). In the middle section, the four soloists create a great sense of drama before the music returns to the opening section. Expansive, and creating a sense of utter depression and despair, the movement nevertheless concludes in a somewhat hopeful coda.

Movements 2 to 9 meditate on the poetic idea of sharing in the suffering of Jesus. A mournful quartet for soloists and orchestra in movement 2 is followed by an ominous march for chorus and orchestra that unabashedly relies on the operatic conventions of Verdi. This sense of operatic drama is further emphasized in the fourth movement, a highly dramatic aria for the bass soloist, whose tormented musical lines are momentarily softened by angelic voices intoning a simple chorale melody. An angry musical outburst interrupts the serenely flowing melody in the fifth movement, while movement 6 presents a lullaby for tenor soloist and male chorus.

Movement 7 features a seemingly innocent contrast between the longing melody in the strings and the unadulterated voices of the chorus. This sense of longing and tenderness finds its continuation in the duet for soprano and tenor in the eighth movement. The march-like aria for alto soloist in the ninth movement takes its musical bearings from the dramatic style of Handel, with pulsating rhythms gradually replaced by desperate lyricism. But it is in the final movement that the grief and tenderness expressed in the previous nine movements “is surpassed in an embrace of the joy of transfiguration.” Initially, the music references previous movement but quickly builds into an impressive Handelian fugue. Tonality is transformed into a radiant major, and a glorious Beethovenian finish reveals the inner light amongst the earthen darkness.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvorák: Stabat Mater, Op. 58, B. 71 (Marie-Noelle Cros, soprano; Catherine Cardin, alto; Patrick Garayt, tenor; Andre Cognet, bass; Paul Kuentz Chorus; Paris Paul Kuentz Chamber Orchestra; Paul Kuentz, cond.)