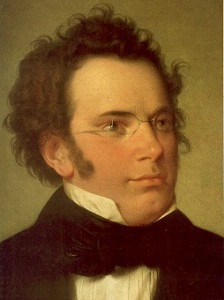

Franz Schubert

Franz Schubert

String Quintet in C major, Op. 163, D. 956

(Stern, Casals, Tortelier, Schneider, Katims) (1956)

In the autumn of 1822, Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828), a quiet, shy, gentle and introverted man of short stature, contracted syphilis. Affectionately called “Schwammerl,” a Viennese dialect word meaning “tiny mushroom,” Schubert was romantically involved in a series of submissive relationships with other men, yet frequented the heterosexual bordellos of the Austrian capital. Within a few weeks of infection he began to exhibit symptoms, which included symmetrical rashes on the palms of his hands, headaches, dizziness and the loss of his voice. He was admitted to the Vienna General Hospital for six months, where he received the treatments considered appropriate at that time. Despite taking numerous cold baths, extensive fasting and the administration of copious amounts of mercury, Schubert clearly sensed that his life was going to be cut short. His personal physician Von Rinna recommended a move to the country, where Schubert would be able to reach fresh air and exercise more easily than he could in the heart of the city.

In October 1828, Schubert moved into a new house and even walked to Eisenstadt to visit Haydn’s grave. A school friend observed, “on walks, [Schubert] mostly kept apart, walking pensively along with lowered eyes and with his hands behind his back, playing with his fingers (as though on the keyboard), completely lost in his own thoughts.” Yet the realization of his impending death not only caused extensive periods of depression and thought of suicide, it also manifested itself in his compositions. Schubert writes, “The product of my genius and my misery, and that which I have written in my greatest distress, is that which the world seems to like best.” Merely weeks before his death, Schubert completed the monumental String Quintet in C major, a composition that has rightfully been called the “composer’s greatest contribution to chamber music.” Although we must guard against relying exclusively on extra-musical considerations, the composition nevertheless expansively combines musical aspects of innocent beauty and sheer terror. Contemporary wisdom holds, that “from a lyrical and dramatic point of view, nothing so ideally perfect has ever been written for strings.” Yet the quintet medium — and the addition of the second cello — apparently caused some uncertainty among performers and scholars who lamented the fact that the work “had not been written as a string quartet.”

Even Joseph Joachim, one of the greatest performers and interpreters of the 19th century could not entirely come to terms with the composition. He writes to Clara Schumann on 24 September 1860. “I played Schubert’s Quintets for two Violins, Viola and two Cellos yesterday. Much of it is beautiful, overflowing with feeling and quite individual; and, unfortunately the whole does not satisfy one! Irregular and with no feeling for beauty in the contrasts! What a pity it is that such a genius should never have fully developed! And yet one cannot help loving dear, good Schubert so much!” At the time of Joachim’s letter, the Schubert quintet had only been in the repertory for 10 years, with the first performance given on 17 November 1850 in the Kleiner Musikvereinssaal in Vienna. By drawing attention to a lack of development, Joachim not only commented on Schubert’s untimely death, but also sensed an aspect of the work that continues to elude performers and scholars alike; essentially, the quintet is symphonic in character, simultaneously drawing on Schubert’s emotional turmoil and on universal yearnings. These contradictory yet entirely complementary aspects of human experience and existence are encapsulated in the contrast between destabilized harmonies exposed to harsh dissonances and tender themes expressing perfection of balance and contentment. Tranquil intimacy — and even popular dance music — contrasts with brooding and menacing passages, and simulated horn calls initiate an exuberant and breathless “Scherzo.” The emotional center of this work, however, is clearly located in the second movement “Adagio.” An outer-worldly hymn, it encompasses passion and emotional intensity projected against the anxiety and desperation of the human experience. I have always wondered why it has been difficult for me to write about this particular composition. Thanks to Eugene Ionesco, I have finally found my answer. I have always looked at it too closely, either in terms of music theory or personal emotional reaction. All it needs, in fact, is a bit of distance and reflection, as this composition is not immediate at all, but resides rather far away. Ionesco writes, “The Schubert C-major quintet is an ethereal vision of eternity rather than an enveloping serenity.” Schubert’s musical vision, born from anxiety, misery and fleeting hope does not address earthly matters after all, but simply provides heavenly reassurance to us all.

Even Joseph Joachim, one of the greatest performers and interpreters of the 19th century could not entirely come to terms with the composition. He writes to Clara Schumann on 24 September 1860. “I played Schubert’s Quintets for two Violins, Viola and two Cellos yesterday. Much of it is beautiful, overflowing with feeling and quite individual; and, unfortunately the whole does not satisfy one! Irregular and with no feeling for beauty in the contrasts! What a pity it is that such a genius should never have fully developed! And yet one cannot help loving dear, good Schubert so much!” At the time of Joachim’s letter, the Schubert quintet had only been in the repertory for 10 years, with the first performance given on 17 November 1850 in the Kleiner Musikvereinssaal in Vienna. By drawing attention to a lack of development, Joachim not only commented on Schubert’s untimely death, but also sensed an aspect of the work that continues to elude performers and scholars alike; essentially, the quintet is symphonic in character, simultaneously drawing on Schubert’s emotional turmoil and on universal yearnings. These contradictory yet entirely complementary aspects of human experience and existence are encapsulated in the contrast between destabilized harmonies exposed to harsh dissonances and tender themes expressing perfection of balance and contentment. Tranquil intimacy — and even popular dance music — contrasts with brooding and menacing passages, and simulated horn calls initiate an exuberant and breathless “Scherzo.” The emotional center of this work, however, is clearly located in the second movement “Adagio.” An outer-worldly hymn, it encompasses passion and emotional intensity projected against the anxiety and desperation of the human experience. I have always wondered why it has been difficult for me to write about this particular composition. Thanks to Eugene Ionesco, I have finally found my answer. I have always looked at it too closely, either in terms of music theory or personal emotional reaction. All it needs, in fact, is a bit of distance and reflection, as this composition is not immediate at all, but resides rather far away. Ionesco writes, “The Schubert C-major quintet is an ethereal vision of eternity rather than an enveloping serenity.” Schubert’s musical vision, born from anxiety, misery and fleeting hope does not address earthly matters after all, but simply provides heavenly reassurance to us all.

More Inspiration

-

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms -

Creating a New Chopin Explore classical music's transformation in popular genres

Creating a New Chopin Explore classical music's transformation in popular genres - Reflections of the Past: George Rochberg’s Carnival Music Listen to how he blends jazz, blues, and classical quotations

- Smetana’s Musical Postcards

The Albumblätter of a Young Romantic Music composed for his wife, friends and students!