American composer Charles Ives (1874–1954) was one of the most original of America’s composers. For one thing, he had a very successful day job in the insurance business, and his early work in the business led to the basics behind modern estate planning. His composition career was kept rather strictly at home, and one of the problems with his repertoire is that instead of getting it out into the public, he kept it at home and continued to revise it. Hence, many of his early works have lost their early characteristics when revised due to his new compositional ideas, so a work initially begun in, say, 1911 might see the light after it was revised in 1947 (The Concord Sonata).

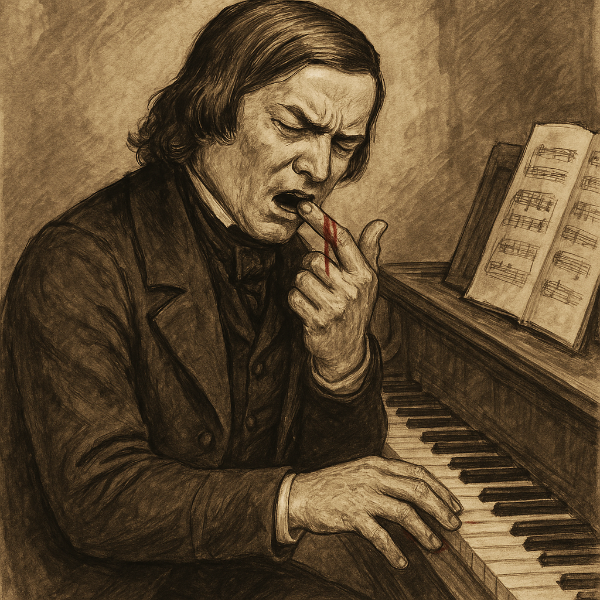

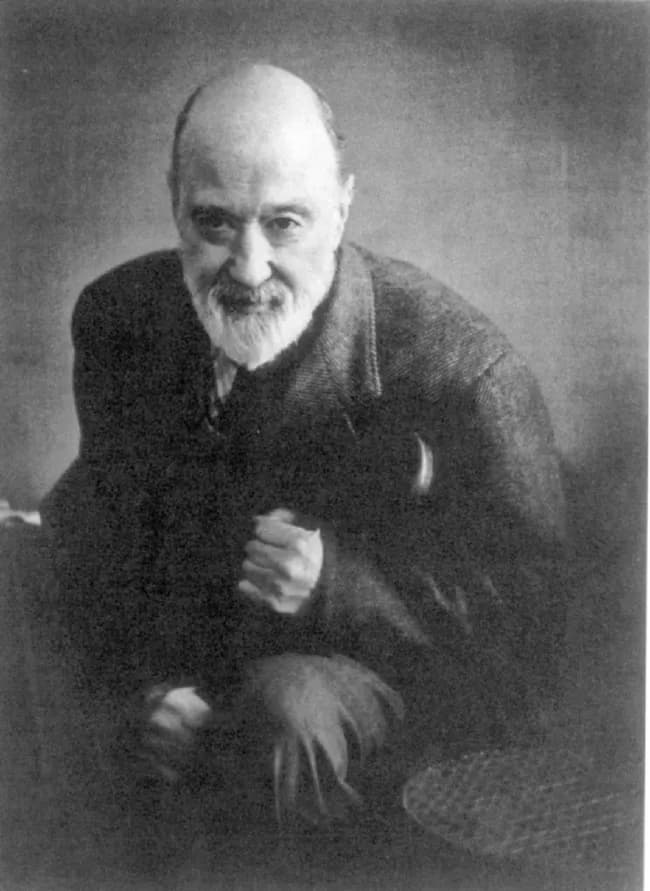

Charles Ives, n.d.

Ives’ father was a music director and teacher, leading bands, choirs, and orchestras and teaching music theory and how to play many different instruments. George Ives taught both Charles and his younger brother Moss their music fundamentals. Charles became an organist in his local church at age 14 and started to write music for the services. When he attended Yale (1894–1898), he played sports, wrote music, and continued as a church organist.

Starting in 1910, he began one of the most creative periods of his life as a composer, building on his earlier works at Yale. Due to health reasons, he stopped composing in 1930 when he retired from the insurance business. Thereupon followed his years of revisions.

He started his first symphony in 1897 and completed it in 1913. Entitled A Symphony: New England Holidays, it was also known as A New England Holiday Symphony or just the Holiday Symphony. Each movement takes up a different holiday, moving through the year from I. Washington’s Birthday (February), II. Decoration Day (last Monday of May), III. The Fourth of July, and IV. Thanksgiving and Forefathers’ Day (last Thursday in November and 22 December). The days coincide with the seasons: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall/Winter.

Ives’ idea about the work was that it reflects a grown-up’s memory of childhood, writing, ‘Here are melodies like icons, resonating with memory and history, with war, childhood, community, and nation’. We can hear Ives’ own recollections of seasonal celebrations with the sound of his father’s band in one ear, the feeling of the seasons (hence the cold and dreary February morning that opens the first piece), the sound of dances for the holidays, and so on. It’s immensely personal and, at the same time, cognizant of the world outside his own ears.

Clara Sipprell: Charles Ives (Washington, DC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

The first movement celebrates the first president of the United States. Washington’s birthday was 22 February 1732, and starting in 1885, it was a national holiday. In 1971, the official celebration day was moved to the third Monday in February and because Abraham Lincoln’s birthday was 12 February 1809, the holiday was renamed to President’s Day, celebrating both leaders at once.

The first movement starts off on ‘the dismal, bleak, cold weather of a February night near New Fairfield’, Connecticut, before going off into a mix of barn dances and popular songs. In this image, taken in Louisville, Kentucky, of a parade on Washington’s Birthday, 1918, we can see how the spectators are all bundled up and all the flags and bunting hanging from the buildings. In the dance section, there’s a tribute to farmers who play their jaw’s harps, a tribute to fiddler John Starr (d. 1890) and ends with the traditional country dance final song, Goodnight Ladies. The ending is like a dream, drifting off while still echoing in the mind.

Military band parading on Washington’s Birthday, 1918, Louisville Kentucky (National Archives, 165-WW-92J-002)

Charles Ives: A Symphony: New England Holidays – I. George Washington’s Birthday (Chicago Symphony Chorus; Fred Spector, jaw’s harp; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

The second movement, Decoration Day, calls for both an on-stage band and an invisible off-stage band. Decoration Day celebrated the dead of the American Civil War (1861–1865), where public parades would end up in the city cemetery where the war graves would be decorated. The first Decoration Day was held in 1868, just 3 years after the end of the war. Originally only intended to recognize the dead from the Union side, the holiday was extended within a few years to the dead of both Union and Confederate sides. By 1890, the holiday was observed across the entire United States. In 1971, it was standardized as Memorial Day, to be held on the last Monday in May, and to recognize the war dead of all conflicts.

In Ives’ world, Decoration Day started with his father’s marching band assembling at the Soldiers’ Monument in the centre of Danbury, Connecticut, and marching to the Wooster Cemetery. There, Charles Ives would play Taps, the bugle call signalling the end of the military day. The bugle call was also used at the end of military funerals. Leaving the cemetery, the band would play ‘David Wallis Reeves’ 1876 march for the Second Regiment of Connecticut’s National Guard. In Ives’ mind’s ear, other tunes in major and minor keys also appear, including Marching Through Georgia and Tenting on the Old Camp Ground, two well-known Civil War songs. These ‘shadow songs’ are performed by the off-stage band, and it’s only on the last note of Taps that the main band enters the celebration.

Honor the Brave Poster, 1917 (Library of Congress)

Charles Ives: A Symphony: New England Holidays – II. Decoration Day (Chicago Symphony Chorus; Fred Spector, jaw’s harp; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

Fourth of July, is the exciting central movement. Starting quietly, it builds up to a tremendous emotional high with fireworks, the traditional end of the day’s celebrations. This is one of Ives’ most interesting works, particularly in how he mixes a dozen songs, national and popular, sacred and secular, ethnic and military into a sound mix that is unmatched in classical music. Starting with Columbia, Gem of the Ocean, Ives also interweaves selections from Yankee Doodle, Dixie, The Battle Cry of Freedom, Henry Clay Work’s Marching Through Georgia, The Battle Hymn of the Republic, The Sailor’s Hornpipe, The White Cockade, Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! The Girl I Left Behind Me, Hail, Columbia, Garryowen, The Irish Washerwoman, My Country, ‘Tis of Thee, John Stafford Smith’s The Star-Spangled Banner, Vincenzo Bellini’s Katy Darling, and Henry Clay Work’s Kingdom Coming.

Fourth of July Fireworks, 2022

Charles Ives: A Symphony: New England Holidays – III. Fourth of July (Chicago Symphony Chorus; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

The year ends with Thanksgiving Day and Forefather’s Day, the latter a Connecticut-local holiday. America’s Thanksgiving Day recognizes the celebration of the Pilgrims at their first harvest festival in Plymouth, Massachusetts, traditionally dated to November 1621. It became a national holiday in 1789 after a proclamation by President George Washington. Starting in 1942, it was normalized to the fourth Thursday in November.

In this movement, the first to be written of the whole work, Ives sought to capture the austerity and simplicity of the Pilgrims’ life and philosophy. He originally wrote the work as a prelude and postlude for organ in 1897 for a Thanksgiving Day service. He adapted it for orchestra in 1904 and, as he did in other movements, incorporated known music, such as the hymn tunes for ‘God! Beneath Thy Guiding Hand’ and ‘The Shining Shore’. Simple is what he intended but, in the end, the otherwise conservative work has ‘a scythe or reaping harvest theme which is a kind of off-beat, off-key counterpoint’, as his student Henry Cowell noted. The celebrating chorus at the end brings us back to the church ceremony where we started but in a considerably different frame of mind.

Jennie A. Brownscombe: Thanksgiving at Plymouth, 1924 (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts)

Charles Ives: A Symphony: New England Holidays – IV. Thanksgiving Day (Chicago Symphony Chorus; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

Ives wrote four numbered symphonies, the Holidays Symphony, and his unfinished Universe Symphony (1928). Although the Holidays Symphony appears in his work list dated 1919, it wasn’t a coherent four-movement work for decades. The first three movements received individual performances in the 1930s (in San Francisco, Havana, and Paris). It was only performed as a complete work on 9 April 1954, five weeks before Ives’ death on 19 May 1954.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter