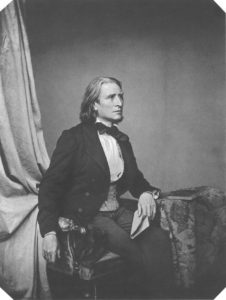

Franz Hanfstaengle: Franz Liszt (1958)

The problem for Liszt was how to expand the orchestral genre into something less confining than the symphony – 4 movements, alternating slow and fast, contrasting triple section. Sigh. It’s all so old. Ok, we have the concert overture, but again, this was an old form. What about emotion, feeling and moods, the whole Romantic idea?

Hence, the symphonic poem. A single movement work that could encompass all the passion, all the ideas, all the emotion that Liszt, that singular man of the world, could compress into a single work. These are pieces of program music, i.e., music built around a pre-existing idea.

Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein (1847)

Liszt’s first work, Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne (What one hears on the mountain), was based on a poem by Victor Hugo looking at the contrast between Nature’s perfection and the misery of man. The second work, Tasso, Lamento e Tionfo, is based on ideas about the 16th century Italian poet Torquato Tasso as expressed in poems by Goethe and Byron.

Les Préludes, given its premiere in 1854, was the first work formally called a ‘symphonic poem.’ As with much of Liszt’s work, Les Préludes and the two earlier works were revised and rewritten and re-orchestrated, etc. and so the later title of ‘symphonic poem’ was applied to the two earlier works.

The work started out as the overture to a choral setting of four poems by Joseph Autran. The Autran work, Les quatre éléments, was made up of four poems: La terre, Les aquilons, Les flots and Les astres. Les Préludes as we now know it, uses material from the choral setting but then was separated and made into its own work. To obscure the connection with the choral music, Lizst gave it the title of Les préludes (d’après Lamartine), referring to an Ode by that name in Alphonse de Lamartine’s 1823 collection Nouvelles méditations poétiques.

There’s very little in Lamartine that would connect with Les Préludes, but when the score was published in 1854, there was a text preface in the score:

What else is our life but a series of preludes to that unknown Hymn, the first and solemn note of which is intoned by Death?—Love is the glowing dawn of all existence; but what is the fate where the first delights of happiness are not interrupted by some storm, the mortal blast of which dissipates its fine illusions, the fatal lightning of which consumes its altar; and where is the cruelly wounded soul which, on issuing from one of these tempests, does not endeavour to rest his recollection in the calm serenity of life in the fields? Nevertheless man hardly gives himself up for long to the enjoyment of the beneficent stillness which at first he has shared in Nature’s bosom, and when “the trumpet sounds the alarm”, he hastens, to the dangerous post, whatever the war may be, which calls him to its ranks, in order at last to recover in the combat full consciousness of himself and entire possession of his energy.

These words, written not by Liszt but by his companion, Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, that gives the key to the work. In a letter he wrote in 1857, Liszt also says that the title, Les Préludes, could also be referring to his own compositional development.

Carl Van Vechten: Dean Dixon (1951)

Liszt’s new idea wasn’t universally accepted, with the critic Eduard Hanslick, himself an advocate of ‘absolute music,’ i.e., music that exists for the sake of its self, rather than to represent another idea, thought that the symphonic poems’ need to rely on an external programme made it less than profound. Another critic found himself overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of the music: ‘The poetry we listened for in vain. It was lost as it were in the smoke and stunning tumult of a battlefield.’ Nonetheless, Les Préludes is regarded as the most popular of the thirteen symphonic poems that Liszt wrote.

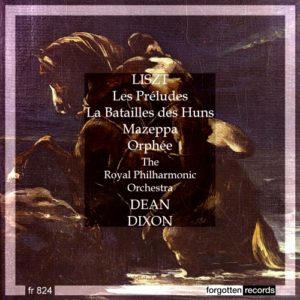

In this recording, made in October 1953 by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, directed by Dean Dixon, Liszt’s emotions and feelings about the great question posed by the work, ‘What else is our life but a series of preludes to … Death?’ come through in a lively bright recording.

Liszt: Les Préludes, Poème Symphonique N° 3, S. 97

The conductor of this work, Dean Dixon (1915-1974), was an American conductor who left the US in 1949 because of lack of opportunities due to his colour.

Although he guest-conducted some of the leading orchestras of the day, including the New York Philharmonic and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, and was the winner of the Ditson Conductor’s Award in 1948, he couldn’t get a permanent appointment. Abroad, he conducted the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra in 1950 and 1951 before becoming the principal conductor of the Gothenberg Symphony from 1953 to 1960. He also went on to become the principal conductor of Australia’s Sydney Symphony Orchestra from 1964 to 1967, and the Hessischer Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester in Germany from 1961 to 1974.

Performed by

Dean Dixon

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Recorded in 1953

Official Website