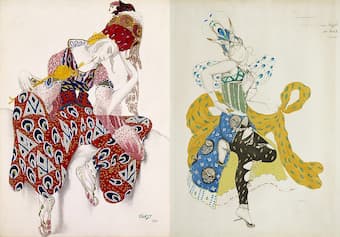

Leon Bakst: Sketch for La Péri’s costume (1911)

Commissioned in 1911 by Serge Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes, the ballet by Paul Dukas, La Péri, had a difficult birth. Dukas came up with the scenario and then wrote the music; choreography, design and stage decoration followed. Originally intended for Natalia Trouhanova as the Peri and Vaslav Nijinsky as Iskender, Diaghilev pulled the production because he thought that Trouhanova wasn’t the right partner for Nijinsky. In the ensuing arguments, Trouhanova refused to sign her contract and the entire production was cancelled.

Leon Bakst: Sketch for Iskender and La Péri (1911)

Trouhanova commissioned her own choreographer, Ivan Clustine, maître de ballet at the Paris Opéra Ballet, to create the dance with décor and costume designs by René Piot. Jacques Rouché, a French art and music patron took over the production and placed it in the 1912 season at the Théâtre du Châtelet. As the promoter of the project, Trouhanova made decisions on changes to the scenario, staging, and the characters. She also worked closely with the choreographer to tie the music closer to the dance. Dukas conducted the Concerts Lamoureux orchestra at the premiere.

René Piot: Sketch for back of the Péri’s costume (1912)

The idea of the Péri comes from Persian mythology, where they are exquisite, winged beings known for their beauty.

If we look at the title for the work, Dukas called La Péri a ‘poème dansé’, which is a curious distinction for a work that was intended to be a ballet from the beginning. Dukas had been interested in the relationship of music to the other arts, and he wrote about this in two books, La Musique et la littérature (1892) and La Déception scénique (1896). Dukas saw music having an interdisciplinary function, springing from a poetic idea to become a unified whole when combined with music and drama or dance. We see this in La Péri, where Dukas first came up with the poetic idea (the scenario) to which the music and dance are fitted.

The scenario sets a beautiful scene, as Iskender seeks the Flower of Immortality to prolong his life:

La Péri (1931), choreographed by Ashton, with Alicia Markova and Frederick Ashton and additional dancers.

(Photo by Pollard Crowther)

It happened that, as his youth came to an end, the Magi having observed that his star was growing pale, Iskender travelled through Iran, seeking the Flower of Immortality. The sun dwelt three times in its twelve houses without him finding it, until he came finally to the ends of the Earth, to the point where it joined the sea and the clouds. And there, on the steps that lead to the court of Ormuzd, a Fairy lay, sleeping in her jewelled robe. A star shone above her head, her lute rested on her bosom and in her hand the Flower shone. And it was a lotus like the emerald, undulating like the sea in the morning sun. Iskender leant noiselessly over the Sleeper, and, without waking her, stole the Flower, which suddenly became, in his fingers, like the noonday sun on the forests of Ghilan. But the Fairy, opening her eyes, clapped her hands together and cried out, for she could not now mount again to the light of Ormuzd. Meanwhile Iskender, looking at her, admired her face that surpassed in delight even that of Gurdaferrid. And he desired her in his heart, so that the Fairy knew the King’s thought, for in the hand of Iskender the lotus grew purple and became like the face of desire. Thus the servant of the Pure knew that this flower of Life was not destined for him, and she leapt forward to take it back, as light as a bee, while the Invincible Lord drew the Lotus away from her, divided between his thirst for immortality and the delight of his eyes. But the Fairy danced the dance of the Fairies, always coming nearer, until her face touched Iskender’s, and finally he gave it to her, without regret. Then the lotus seemed of snow and of gold like the height of Elbourz in the evening sun. The form of the Fairy seemed to melt into the light from the calyx and soon nothing could be seen except a hand, lifting up the flower of flame that vanished into the sky above. Iskender saw her disappear, and understanding that this signified his coming end, he felt the shadow encircle him.

In her choreographic direction, Trouhanova gave the Péri directions when to ‘gesture’ and when to dance; Iskender’s role is given as one of ‘gesture,’ with the Péri being the sole dancer. This was changed by later choreographers, particularly as male dancers, such as Frederick Ashton, took over direction of the work in the 1930s. Ashton’s 1931 production also added additional peris.

The work opens with a fanfare, performed sole by the brass section.

Paul Dukas: La Péri – Fanfare (Lille National Orchestra; Jean-Claude Casadesus, cond.)

The music for the ballet combines Romantic and Impressionistic styles and is considered one of Dukas’ most mature pieces. Although the work never attained the fame of his symphonic poem The Scorcerer’s Apprentice, it has a beauty and French style that shows us Dukas’ skill. A review of a 1921 performance at the Paris Opéra Ballet took great care to praise the score, saying that everyone knows the score and it is ‘in my opinion, a masterpiece….’ The reviewer saw it in the line of symphonic poems created by Berlioz and Liszt, but a more modern creation, combining ‘the two great themes that form the backbone of the poem: the romantic theme of Iskender, [the] the orientalist and venomously sensual theme of the dance of the Peri.’

Paul Dukas: La Péri – La Péri (Lille National Orchestra; Jean-Claude Casadesus, cond.)

This work was a success and entered the repertoire of the Paris Opéra Ballet. Now, it’s largely forgotten, with few performances in the regular repertoire.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter