Benjamin Britten

Frank Bridge: The Sea

Britten later reports of being “knocked sideways” by the composition, “especially by the sensuous harmonies found in the “Moonlight” movement.” Britten returned for the 1927 festival and brought some of his own compositions with him. Bridge was sufficiently impressed with Benji and invited him to London to take lessons. Initially, Britten would make regular day trips to London for his composition lessons, and at age 16 entered the Royal College of Music in London. The assessment of Frank Bridge’s influence on Britten varies greatly, with some scholars suggesting, “Britten’s abilities as an orchestrator were essentially self taught.” Others vehemently argue the importance of Bridge’s contributions to the budding composer, and it seems that the “4 Sea Interludes” from the opera Peter Grimes do support the latter notion.

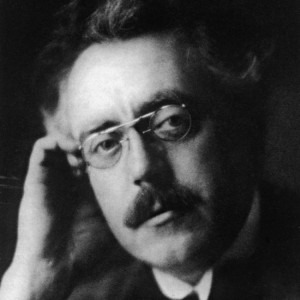

Frank Bridge

During his early days in London, Britten continued to study privately with Bridge, who introduced him to the music of continental Europe. Above all, it was the music of Arnold Schoenberg, which seriously fascinated Bridge. Bridge had already employed Schoenberg techniques in his String Quartet No. 3, and passed his excitement to the young Britten, who wrote on 7 April 1930, “I go to a marvelous Schoenberg concert. Including Chamber-Symphony, Suite Op. 25 and Pierrot Lunaire. I like the last the most, and I thought it most beautiful.” Britten heard Schoenberg’s first Chamber Symphony, which was originally completed in 1902, in a highly effective transcription for flute, clarinet, violin, cello and piano fashioned by Anton Webern in 1923.

Arnold Schoenberg: Chamber Symphony No. 1, Op. 9 (Arranged A. Webern)

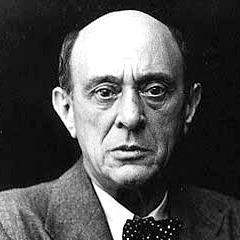

Arnold Schoenberg

Benjamin Britten: Sinfonietta, Op. 1

On 8 February 1933, Britten reports that he had gone to BBC concert hall, where “Schoenberg conducts his Op. 31 variations. What I could make of it owing to a skin-of-its teeth performance, was rather dull, but some good things in it. Meet Schoenberg in interval.” In 1949, Britten conducted a concert in the USA, and both Schoenberg and Stravinsky were in the audience. During intermission, both composers “paid Britten the courtesy of calling on him in the green room. But Britten turned the two distinguished visitors away.” It was something he felt guilty about for the rest of his life. Please join me next time when we explore the influence of Alban Berg’s music on Benjamin Britten.