Practicing has never been more challenging than right now while for the foreseeable future scheduling live concerts is in doubt. Amateurs, students, professionals—we’re all in the same boat. Without a performance on the horizon I too am unmotivated to practice. I try, just a little and I’m shocked. “It sounds so bad!” I say to myself. “My fingers feel like wet noodles. Who’ll want to hear me play if I sound like this?”

Practicing has never been more challenging than right now while for the foreseeable future scheduling live concerts is in doubt. Amateurs, students, professionals—we’re all in the same boat. Without a performance on the horizon I too am unmotivated to practice. I try, just a little and I’m shocked. “It sounds so bad!” I say to myself. “My fingers feel like wet noodles. Who’ll want to hear me play if I sound like this?”

What can we do to motivate ourselves?

Several colleagues are trying to address the struggle. Violinist Hilary Hahn has embarked on another #100daysofpractice on Twitter. Many other artists have created videos and virtual classes to help encourage us. Here are a few hints:

1. FIND YOUR MUSE: Before you begin set aside 20-30 minutes to get inspired. Listen to a piece of music you love. Anna Lapwood, Director of Music at Pembroke College in Cambridge, UK, suggest taking 15 minutes to write a couple of pages in a notebook. “Let your mind go in a stream of consciousness in order to reduce the cacophony of thoughts whirling in your head. Create a distraction sheet, a list of things you need to do that day, or you’re thinking about, so once you begin to practice your mind isn’t cluttered with disruptions.”

Victor Herbert: Cello Concerto No. 1 in D Major, Op. 8 – I. Allegro con spirit (Mark Kosower, cello; Ulster Orchestra; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

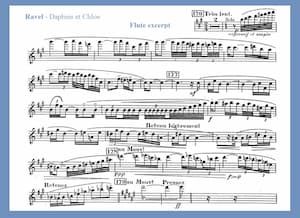

Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé Suite

2. MAKE A PLAN: Set up a practice schedule and a plan. We are creatures of habit. A regular practice time during the day can help. Write down your goals. I suggest a larger objective such as, “I’d like to learn the Victor Herbert Cello Concerto or the difficult exposed flute spots in Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé Suite; or I’d like to learn spiccato and arpeggios this month in the Paganini Caprice No 5, or I’d like to learn second position.”

Then set up a daily goal: 15 minutes on warm-up; 15 minutes on an étude; 20 minutes on intonation in one piece—a ten-minute break—and 10 minutes on a difficult bowing or breathing passage in another piece, then 10 minutes on a left hand or a different challenge in another piece. Write down how it went in your notebook—were you successful? Were your fingers sluggish or fatigued? Did you experience tension or pain? If so please take a break of a few days.

Niccolò Paganini: 24 Caprices, Op. 1 – No. 5 in A Minor (Sergey Malov, violin)

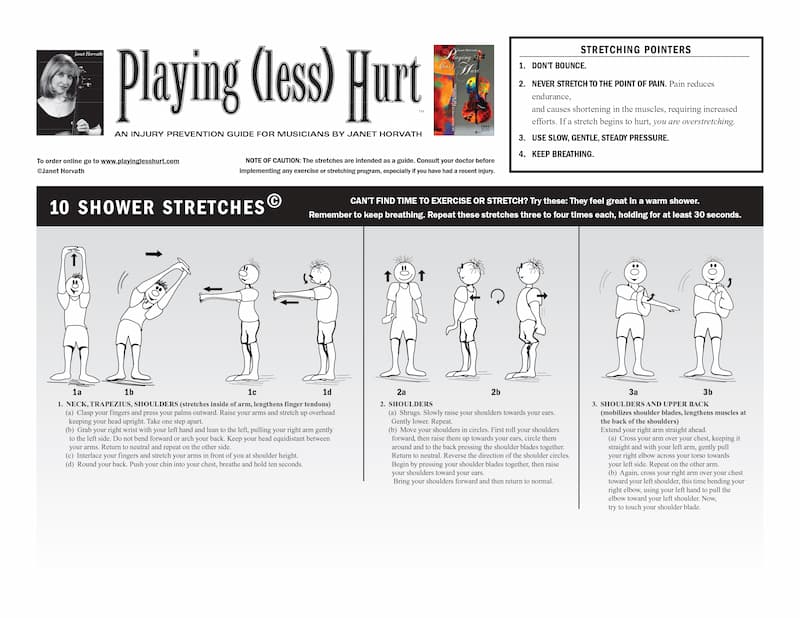

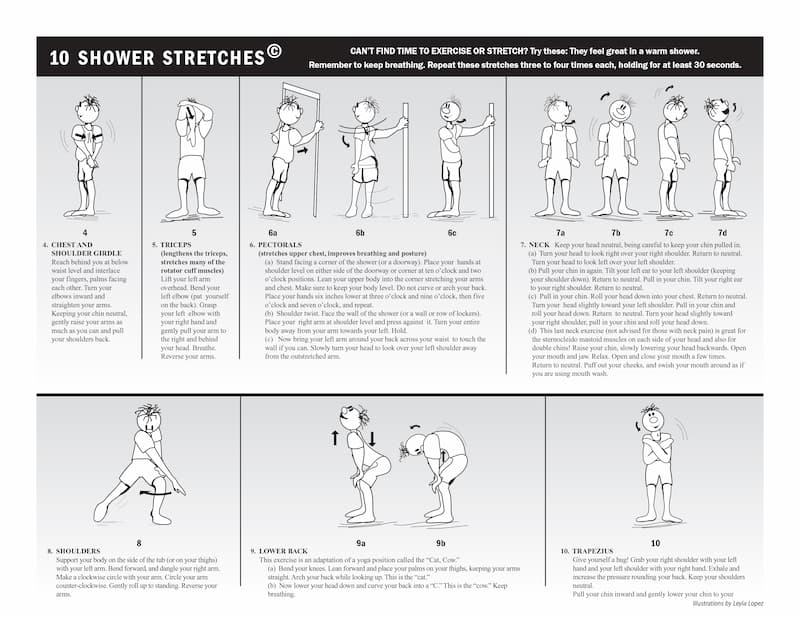

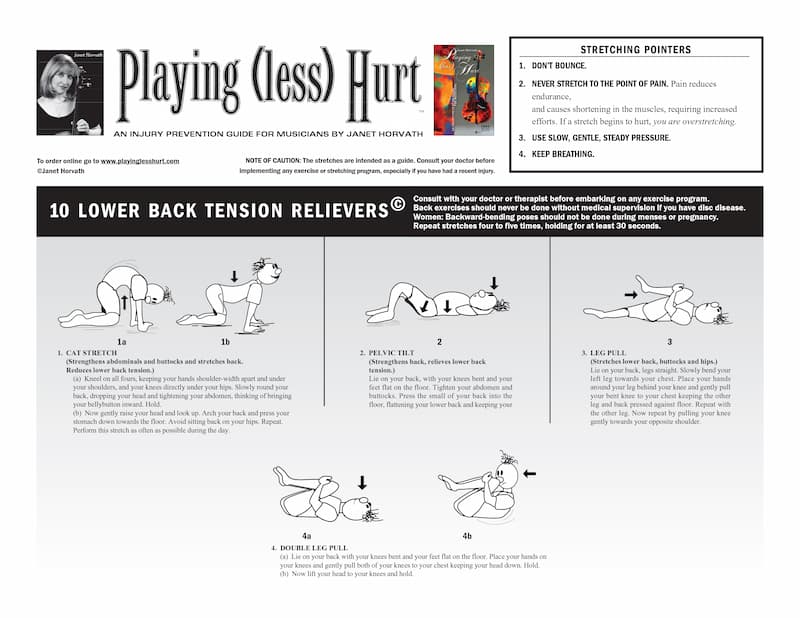

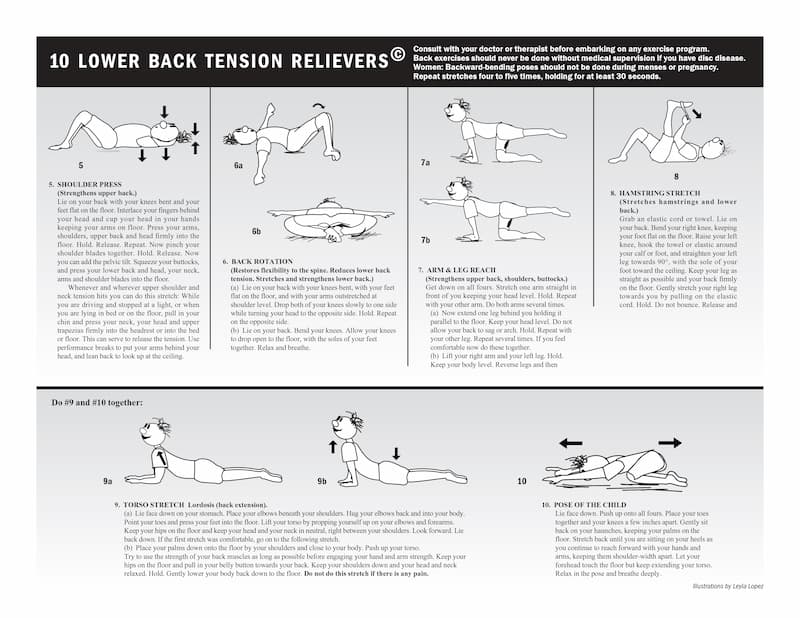

3. BREATHE and WARM UP: away from the instrument. First: Inhale deeply through your nose for four counts; hold your breath for four counts; exhale blowing through your mouth for 4 counts; hold for four counts. Repeat. Shrug and roll your shoulders. Clasp your hands and reach to the sky. Clasp your hands behind you and pull your shoulders backwards slightly. Now do some gentle stretching. These can be done lying down, seated, or in the shower before you practice! Many are from yoga such as the Cat and Cow and the pigeon pose. Before you sit down to your instrument get your blood moving too. Briskly walk up and down the stairs, do some jumping jacks, or jog in place. If you have a routine that works for you, great. Now you’re ready!

4. THINK ABOUT POSTURE: Keep your body in neutral or natural. Sit with your knees descending from your hips and your weight slightly forward on your feet, which allows you to maintain a lumbar curve in your back. Keep your shoulders down and facing forward, your torso facing forward, and your head upright and erect. This is just as important to think about at the computer. Avoid starting right off the bat with ‘technique building’ exercises, difficult etudes, fast scales and arpeggios, or high-range exercises. Warming up at your instrument means beginning Not too high, not too low; not too fast, not too slow. Start in the mid-range of your instrument and focus on continuous breathing, releasing every non-playing finger. Concentrate on ease and flow.

5. VARY YOUR REPERTOIRE: By playing something old, familiar, and a piece you adore you can stay inspired and loose while you learn something new, which may keep you fresh but at the same time may be challenging or even frustrating. You’ll also use different muscle groups thereby reducing the risk of taxing one part of your body. Remember to keep optimistic. Incremental change does occur, and all the small victories are to be celebrated.

6. LISTEN TO YOUR BODY. It’s okay if there are days when you feel like throwing your instrument out the window! I know that feeling. You may be tired after a sleepless night, or tighter that day. We all need time off sometimes and this isn’t a reflection on you as a musician or as a person. Take a break. Read a book. Take a walk. Have some tea (or something stronger) or put the instrument away for a day or two. Never play in pain. Stop immediately, analyze what may have caused the issue, and get help.

7. PLAY WITH JOY AND PASSION. It can be difficult to stay motivated to practice during the best of times. It’s even more difficult now that we don’t have our colleagues to encourage us. Making music is a gift. Be gentle with yourself. Try to be optimistic. Always strive for beauty of sound, beauty of expression, and ease of playing. When you’re stuck play something, or listen to something, or do something that makes you smile.

Find yourself a practice buddy! © The Vault at Music & Arts

8. FIND A PRACTICE BUDDY: So many people I know belong to book clubs. What a great way to share thoughts and ideas, and to keep reading. Writers have writing groups. They share a few pages of excerpts before it’s ready for formal editing or public consumption. Why shouldn’t we musicians form practice clubs? Getting together to talk shop on zoom might be just the inspiration we need. Meeting weekly (or more often) to discuss repertoire, technical issues, trade practice strategies, or share the challenges we experienced that week, especially while we are isolated, could be a priceless encouragement.

Most important: keep reminding yourself that music is what you love more than any other endeavor and it’s worth all the efforts we make to continually improve and to excel.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter