Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Deep river, my home is over Jordan;

Deep river, Lord, I want to cross over into campground.

Oh don’t you want to go to that gospel feast,

that Promised Land where all is peace?

Deep river, Lord, I want to cross over into campground.

African-American Spiritual

“What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro Melodies.” – Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, composer

There is something reminiscent of Brahms’ writing for the piano in the melody, harmonies and textures of Deep River, one of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s 24 Negro Melodies, and if you didn’t know it was by this English mixed-race composer, you might mistake it for a lesser-known work by the great German romantic.

‘Deep River’ is a song about crossing boundaries, physical and metaphorical. Through the richness of the music’s textures, its simple yet memorable melody and its contrasting episodes – from serenity to restless drama – the composer suggests both the physical breadth and depth of a great river, and actual and ideological divides between peoples.

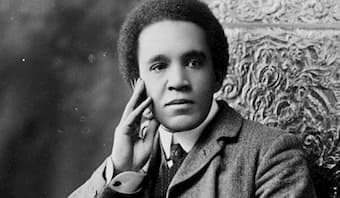

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born in London in 1875 and showed early musical promise. He took violin lessons from a young age and studied at the Royal College of Music from the age of 15, initially under Charles Villiers Stanford (who also taught Gustav Holst, Rebecca Clarke, and Ralph Vaughan Williams, amongst others). He was later helped by Edward Elgar. His most significant work is ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast’, a cantata inspired by the poem by Longfellow and recognised alongside Handel’s ‘Messiah’ and Mendelssohn’s ‘Elijah’, but he also wrote song settings (including a setting of ‘Kubla Khan’ by his near-namesake, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge), and chamber works.

© Alfred Music

‘Deep River’ is one of the best-known spirituals; Coleridge-Taylor first encountered it in a performance by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an African-American acapella ensemble, which he heard in concert when they visited London. Coleridge-Taylor sought to integrate traditional African music into the classical tradition, not unlike Brahms and Dvořák in their use of Eastern European and American folk music idioms in their works. ‘Deep River’ is one of 24 Negro Melodies Transcribed for the Piano, which Coleridge-Taylor published in 1905. In general, he did not use entire folk melodies in his compositions, preferring to create fantasies based on the original melody. In ‘Deep River’, the composer uses only the first four bars of the song, and dispenses with the verse-chorus-verse organisation – though fragments of the main melody return throughout the piece.

The music opens with hushed, arpeggiated chords and the timeless melody, but it quickly moves into more ambiguous harmonic territory, and at this point becomes more redolent of Brahms. The next section departs from the original in its fantasy-like treatment of the original melody, with ornamentation and considerable expressive elements. This is followed by a dramatic interlude of up-tempo octaves, almost a fanfare, before a brief return to the original melody, and a modulation into A-flat major.

The octave fanfare returns, and the music gradually subsides, in both volume and speed, before returning to the opening melody, in the original key of E major. The piece ends in a rather Lisztian fashion, with rolling E major arpeggios, marked pianissimo, and two hushed chords.

For the pianist, the music has much scope for expression and generous use of rubato will only add to the emotional power of the piece. Treat it like a late Brahms Intermezzo, with close attention not only to the main melody but also the interior details, and you have a work of great romanticism and richness.