Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

On the very last Saturday of 1899, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor married Jessie Sarah Fleetwood Walmisley in a parish church at Selhurst, near Croydon, England. Just a regular wedding ceremony, I hear you say, but in reality it followed some very tense months. Jessie’s family was vehemently opposed to the marriage, and they tried everything in their power to prevent it. Jessie was the niece of composer Thomas Walmisley, and the youngest of eight children. The family lived in Croydon, and her father and brother were both bankers in London. Samuel on the other hand was the mixed-race son of Dr. Daniel Hughes Taylor—a physician from Sierra Leone and the English woman Alice Hare Martin—and had been raised by his mother alone.

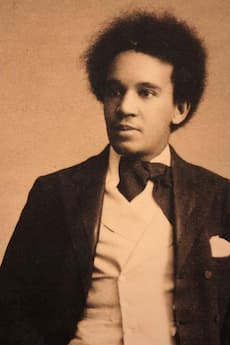

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, c. 1893

Coleridge-Taylor told a friend, who related “her parents were bitterly opposed to their daughter becoming the wife of a ‘Blackie,’ as they were in the habit of calling the young composer…They considered their would-be-son-in-law as being only a generation removed from the status of an African savage, and they tearfully warned their Jessie that if she married him in all probability he would inflict upon her strange shifts—perhaps take her to the Dark Continent, compel her to live amongst his naked relations and wear no clothes.” Given such spiteful opposition, Jessie and Samuel tried for a separation, but a clergyman supported the idea that they should get married, nevertheless.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Clarinet Quintet, Op. 10 (Klaus Hampl, clarinet; Quartetto di Roma)

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor with his family

The relationship between Samuel and Jessie was based on a love for music, and on a shared educational background at the Royal College of Music. Samuel had been a violin student at the RCM and he continued his composition studies with Charles Villiers Stanford from 1893 to 1897. Trying to make a living as a professional musician, Samuel managed to have his clarinet quintet scheduled for performance on 9 December 1897, and he taught at the Croydon Conservatoire of Music. He became associated with the local all-female Brahms Choir, and he conducted the local string orchestra comprised of mostly women. Late Victorian Society had strong conventions about young unmarried women. They could take a train or tram for music lessons or attend a concert, “yet lacked such freedom in other activities.” Participating in music enabled many women to break with highly restrictive social conventions. The RCM attracted a substantial number of women, and the Croydon amateur choirs were often criticized for lacking “a balance between male and female voices.” One of the young women participating in Croydon’s musical activities was Jessie Walmisley, who had studied voice at the RCM from 1890 to 1893. When she was looking for a local violinist to study some Schubert duets for piano and violin during the summer of 1892, their paths first crossed. Samuel was only seventeen, and she was six years his senior.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: 5 Songs of Sun and Shade, No. 4 “Thou art risen my beloved” (Dorothy Maynor, soprano; Árpád Sándor, piano)

Jessie Coleridge-Taylor, Avril and Hiawatha

When the Croydon Conservatoire of Music gave its annual concert on 4 February 1898, Samuel conducted the string section from the conservatory orchestra, and Jessie sang songs by Schubert and by Coleridge-Taylor. The Musical News observed, “her singing of the latter made a deep impression.” The music critic must clearly have sensed that Samuel and Jessie were deeply in love. When the relationship became public, her four siblings intensely disliked the idea of a black brother-in-law, and we have already seen what her parents thought of the relationship. Immensely frustrated by family prejudices and bigotries, Samuel channeled his energies into a cantata for tenor, chorus, and orchestra. He had long been attracted to the 1855 epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The epic relates the fictional adventures of an Ojibwa warrior named Hiawatha and the tragedy of his love for Minnehaha, a Dakota woman. Clearly, the young composer was attracted to the customs of Hiawatha’s people and their strong group solidarities, which “contrasted decidedly by the behavior of the Walmisley tribe.” The first part of an eventual trilogy of cantatas, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast became an instant hit. Premiered on 11 November 1898 at the RCM, Sir Arthur Sullivan wrote after that performance, “Much impressed by the lad’s genius. He is a composer, not a music-maker. The music is fresh and original, he has melody and harmony in abundance, and his scoring is brilliant and full of color—at times luscious, rich and sensual.” The success of the work was immediate and international.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Scenes from The Song of Hiawatha, Op. 30: I. Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast: Onaway! Awake beloved (William Brown, tenor; London Symphony Orchestra; Paul Freeman, cond.)

Avril Coleridge-Taylor

A music critic wrote, “we are apt to connect the musical attainments of men of colour with the primitive minstrelsy which relies for its support on clattering bones and throbbing banjo, but Coleridge-Taylor had proved his ability to scale the loftier heights of the musical Parnassus and to meet on equal terms the best of our white composers.” Faced with the international fame and fortunes of their proposed son-in-law, the Walmisley family finally relented and even attended the wedding. The happy union produced a son named Hiawatha (1900-1980), aptly named after the fictional hero that made Coleridge-Taylor famous. The couple also had one daughter, Gwendolyn Avril (1903–1998), who started composing at an early age, and later became a conductor/composer under the professional name of Avril Coleridge-Taylor. Samuel became known as the “African Mahler,” and his compositions inspired an African American group of singers to form the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society in Washington, DC. In all, Samuel visited North America three times, and he “saw it as his mission in life to help establish the dignity of African American.” For a time, he even contemplated immigration to the United States. In England, Coleridge-Taylor unassumingly composed, taught at Trinity College of Music, conducted numerous choral societies, and even conducted in the famed Handel Society from 1904 until his premature death from pneumonia on 1 September 1912.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Symphonic Variations on an African Air, Op. 63 (Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; Grant Llewellyn, cond.)

A wonderful, inspiring story, very well told.Pat McL