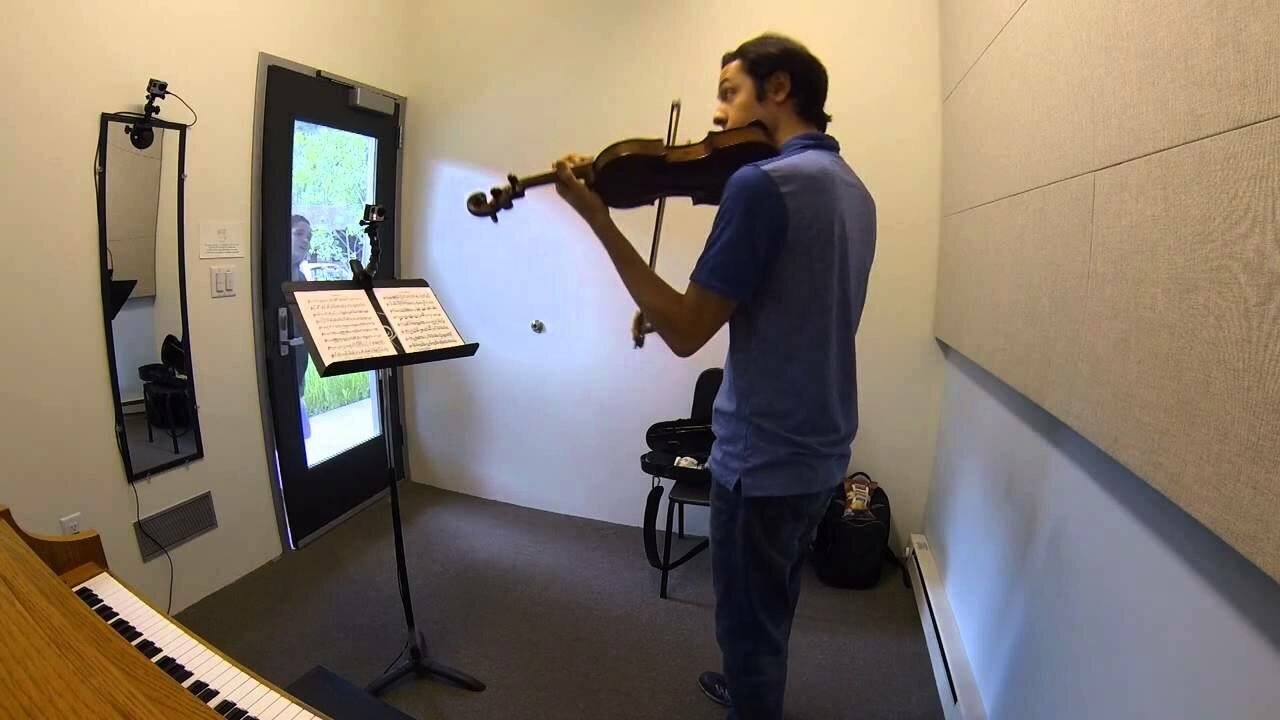

Practicing is the musician’s day-to-day work and when done well it is undertaken with the focus and concentration of an elite athlete to achieve the necessary technical and artistic facility to perform complex repertoire.

As a child, learning the piano from around the age of 5, I found practising something of a chore: the same piece of music faced me each day on the music desk of the piano, the same tedious exercises to be finessed to please my teacher at the next lesson. At that time I didn’t receive any suggestions from my piano teacher as to how to practice productively. Instead, I engaged in fairly mindless repetitions.

It was only as I matured as a musician that I began to understand the significance of deep, thoughtful practice, and how this approach would shape and secure the music I was learning. This was more than demonstrated to me when I returned to the piano in my late 30s after an absence of some 20 years and I revisited some of the repertoire I had learnt and enjoyed as a teenager; it was quite evident which pieces had been practiced more carefully for these were the ones whose notes and phrases still felt familiar under the fingers, and were the pieces most easily revived. It was a very clear indication that the body does not forget, such is the power of procedural (or muscle) memory.

Debussy: La mer – No. 2. Jeux de vagues (Philharmonia Orchestra; Pablo Heras-Casado, cond.)

© Enjoy Steem Blog

Practicing should never feel like a chore. One should approach each practice session with an open, curious mind and a sense of excitement and adventure, to start each session with the thought “what can I do today that’s different?”. It’s a constant process of self-critique, reflection and adjustment. Practicing is like being in a riptide – your view of the beach is different every time and on each re-entry to the beach, you notice different or new details.

Music is complex, multi-faceted and rich in detail. For this reason, in our practicing we must be alert to its many subtleties, its highlights and its shadows. Each practice session should be, amongst other things, an exercise in revealing another facet of the music. Paradoxically, this becomes more difficult the better one knows the music: familiarity with the architecture, the organisation of the notes on the stave, the sound and feel of the music, and our physical and emotional responses to it can lead to complacency and then details are overlooked. At this point, we are deeply embedded in the music, undoubtedly a good place to be. Now we must step back, to view the beach from a distance, with new eyes and the benefit of experience, and look again at the music.

It’s remarkable how many details can be missed and how taking a long view can reinvigorate our practicing and breathe renewed life and colour into our music.