Clara Butt, 1897

Clara Butt was an impressive 6’ 2” (1.8 m) tall. As a singer, she had a very wide vocal range, from C below middle C to high A. In her professional debut in 1902, her abilities were noted by the music critic for The World, George Bernard Shaw, who predicted a great career ahead of her. Her career centred around recitals and concerts – her operatic career was extremely limited, singing in only 2 productions of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (one at the Royal College of Music as a student and the other in 1920 at Covent Garden).

She impressed the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns when he heard her in Paris and the English composer Edward Elgar, who wrote his Sea Pictures for her voice.

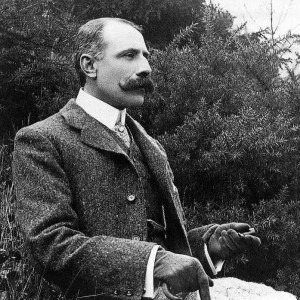

Edward Elgar, c. 1900

The five poems all have sea references, but it is the orchestra that forms the background for the work that truly brings it alive. From the opening of No. 1, the Sea Slumber-Song, where we have the undulating ocean at the beginning and then the colours of the depths being revealed through the skilful orchestration, Elgar sets the scene.

Elgar: Sea Pictures, Op. 37: I. Sea Slumber-Song (Sarah Connolly, mezzo-soprano; Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Simon Wright, cond.)

Alice Elgar late in life

Elgar: Sea Pictures, Op. 37: II. In Haven (Capri) (Sarah Connolly, mezzo-soprano; Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Simon Wright, cond.)

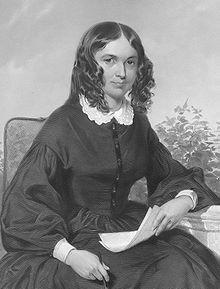

Elizabeth Barret Browning wrote Sabbath Morning at Sea in 1839. The religious poem uses the despair of a sailor who awakes to the glory of the world and is inspired to look higher, to heaven, where there is ‘an endless Sabbath morning,’

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The most-often performed song in the cycle is the fourth, Where Corals Lie. The poet, Richard Garnett had published the poem in 1859. Each verse setting adds another instrument doubling the vocal line: first flute and clarinet (v. 1), then solo cello (v. 2), and cello (v. 4). It is verse 3 that is the most difficult for the singer – there are places where it is to the singer, not the conductor, to set the rhythm and speed – and it is that subtlety that makes each performance differ.

Elgar: Sea Pictures, Op. 37: IV. Where Corals Lie (Sarah Connolly, mezzo-soprano; Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Simon Wright, cond.)

The last movement opens with a storm that builds and crashes. The vocal line, too, builds like waves to crash on the shore. The swimmer of the title seems lost in the storm, looking for his lost love.

Elgar: Sea Pictures, Op. 37: V. The Swimmer (Sarah Connolly, mezzo-soprano; Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Simon Wright, cond.)

Repetition of themes from the first song, such as the opening rocking motion, helps to tie the cycle together musically. We end the cycle in a splash of water and wave and so Elgar made his second appearance in the world, never really to disappear again.