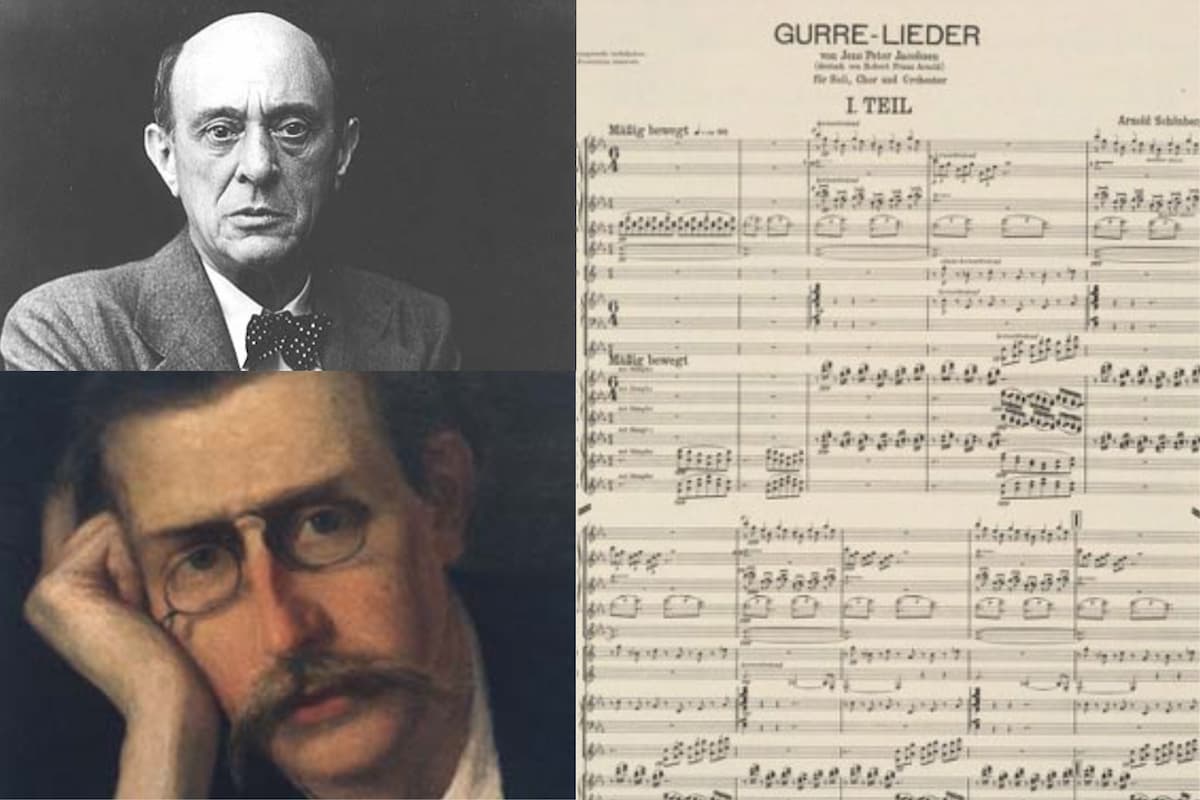

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) rightfully considered himself the musical successor to both Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms. Simultaneously extending their traditionally opposed German Romantic styles, Schoenberg started work on a song cycle for soprano, tenor and piano in 1900.

For his text, Schoenberg selected the dramatic poem “Gurrelieder,” part of the 1868 novella titled A Cactus Blooms by the Danish poet Jens Peter Jacobsen. The novella tells the story of five friends who gather every nine years to witness the rare blooming of the cactus. To pass the time, each friend recites a poem or tells a story. The historically based Gurre legend details the love and passion of King Waldemar for the beautiful maiden Tove. In a fit of raging jealousy Queen Helwig poisons Tove, and when the bereaved king curses God, he is condemned to fly eternally with his henchmen through the night sky. By day, however, Waldemar is fated to search for Tove, who is now transfigured through the splendors of nature. The poet himself provides the final summation, as he describes how nature sweeps away tragedy and death with each sunrise of a new day.

Arnold Schoenberg: Gurrelieder (Karita Mattila, soprano; Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Moser, tenor; Philip Langridge, tenor; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Ernst Senff Choir; Leipzig Radio Chorus; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Simon Rattle, cond.)

For Schoenberg, Jacobsen’s poem held immediate appeal. Beginning work in early March 1900, he composed Gurrelieder in little over two months, with most of the three parts completed in short score. Originally, Schoenberg set the first part of the poem—nine alternating love songs of Waldemar and Tove—as a song-cycle with piano accompaniment. However, on the advice of his mentor Alexander von Zemlinsky, Schoenberg decided to set the entire poem as a work for orchestra, vocal soloists, and chorus. According to Schoenberg, the whole composition was finished in 1901, with only the final chorus in rough sketch and the orchestration still needing work in some places. Financially destitute, however, Schoenberg was forced to take on work arranging operettas by other composers and he even took the job as Kapellmeister at the Berlin Cabaret “Überbrettl.” In the event, Schoenberg only put the finishing touches on Gurrelieder in early 1912.

Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder represents the creative pinnacle of the turn-of-the-century post-Wagnerian era. And that includes a mammoth orchestral apparatus and huge choral forces. 25 woodwinds, 25 brass instruments, four harps, a celesta, 16 different percussion instruments—including iron chains—and 75 strings perform in support of soloists, 3 four-part men’s choruses, and an eight-part mixed chorus. In his guide to Gurrelieder, Alban Berg identifies 35 characteristic motifs that unify the composition. These motifs are not confined to the principal characters, but also characterize aspects of nature, and various emotional states. In terms of vocal treatment, the solo songs of Part I and Part III are not arias in the Wagnerian sense, but dramatic lieder in their structure and lyricism. Schoenberg reserves real innovation for the melodrama “Summer’s Wind” in Part III. Here he uses for the first time the inflected and rhythmic speech patterns known as “Sprechgesang.” Employed as a dramatic and theatrical device to set this section outside the actual story line, it provides a reflection on the legend by the poet himself.

When Franz Schreker conducted the highly successful premiere of Gurrelieder in Vienna on 23 February 1913, Schoenberg turned his back on the audience and refused to acknowledge the ovation. “I was rather indifferent, if not even a little angry,” Schoenberg recalls. “I foresaw that this success would have no influence on the fate of my later works. I had, during these thirteen years, developed my style in such a manner that to the ordinary concertgoer, it would seem to bear no relation to all preceding music. I had to fight for every new work; I had been offended in the most outrageous manner by criticism; I had lost friends and I had completely lost any belief in the judgment of friends. And I stood alone against a world of enemies.” While the 1913 performance of Gurrelieder proved to be Schoenberg’s greatest triumph of his career, it only served to harden the public’s resistance to his subsequent music. Endless enquiries as to why he had not stuck to the style of Gurrelieder eventually forced him to write a long essay entitled “How one becomes lonely.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Schoenberg: Gurre-Lieder / Rattle · Berliner Philharmoniker