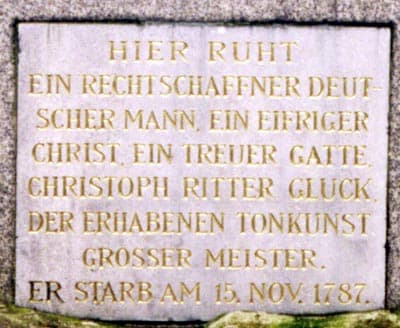

“I endeavoured to reduce music to its proper function,” wrote Christoph Willibald Gluck, “that of seconding poetry by enforcing the expression of the sentiment, and the interest of the situations, without interrupting the action or weakening it by superfluous ornament.” The great reformer of operatic conventions died on 15 November 1787, and he left 35 complete full-length operas plus a number of shorter works. His music greatly influenced the young Mozart, and he subsequently found in Berlioz the culmination of his operatic tradition.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Écho et Narcisse, “L’amour”

Écho et Narcisse

Christoph Willibald Gluck

Gluck found himself in Paris for rehearsals for his lyric drama Écho et Narcisse in the autumn of 1779. Rehearsals did not go well, and the premiere on 24 September was a decided failure, heavily criticised for a colourless subject and a poor poem. A contemporary critic writes on 30 September 1779. “It is true that it would be impossible to set eyes on worse words. The stilted, precious, ludicrous style or this poet goes to unexampled lengths, and his very scheme, which is entirely contrary to the fable, is the most ridiculous thing imaginable.”

The production was discontinued after only 12 performances, and Gluck was not a happy man. We are still not sure when, but Gluck apparently suffered a mild stroke during rehearsals and again after the performance. With his health deteriorating and the disappointment of the Parisian production looming large, Gluck left Paris for Vienna in the middle of October, vowing never to return.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Écho et Narcisse, “Quatuor de Nymphes”

Vienna

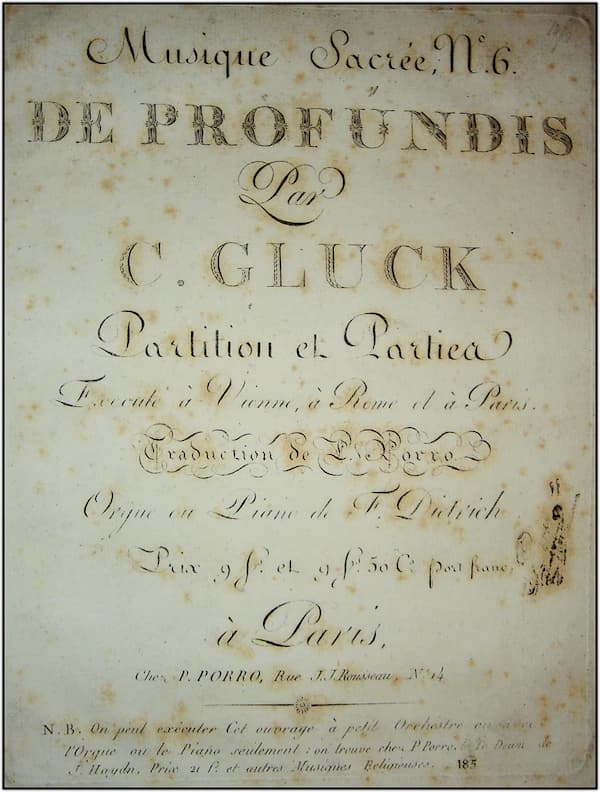

Christoph Willibald Gluck’s De Profundis

Gluck set his mind on staging Écho et Narcisse in Vienna, and by March 1780, his health had been reasonably restored. As he reports, “But as my going to Paris again, nothing will come of it, so long as the words ‘Piccinnist’ and ‘Gluckist’ remain current, for I am, thank God, in good health at present, and have no wish to spit bile again in Paris.” Gluck revised the work, but this “new arrangement” was a failure in Vienna as well; it enjoyed only nine performances.

A new opportunity arose at the end of October 1780 as Gluck was in negotiations with Naples for four operas. Sadly, the death of Empress Maria Theresa prevented the engagement, but Ranieri de’Calzabigi presented Gluck with the libretto of Les Danaïdes, based on a Greek tragedy around the deeds of the mythological characters Danaus and Hypermnestra. However, Gluck was not able to meet the production schedule and asked his student Antonio Salieri to take over the project.

Antonio Salieri: Les Danaïdes (Judith van Wanroij, soprano; Katia Velletaz, soprano; Philippe Talbot, tenor; Tassis Christoyannis, baritone; Thomas Dolie, baritone; Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles Choir; Les Talens Lyriques; Christophe Rousset, cond.)

Antonio Salieri

Antonio Salieri © Wikipedia

On the libretto of Les Danaïdes, Gluck was mentioned as the co-composer, but after the work had received a number of performances, Gluck published a declaration that Salieri should be considered the only creator of the music. Salieri, in turn, wrote in his dedication of the work to the queen. “I wrote it under the eye and under the direction of the famous Chevalier Gluck, that sublime genius, the creator of dramatic music, which he has carried to the highest degree of perfection it is capable of attaining.”

We know from Gluck’s correspondence that he was suffering from ill health again in March 1781. A couple of weeks later, he had a serious apoplectic seizure, which completely paralysed his right side. Unable to write, he dictated a letter to the conductor Valentin at Aiguillon. “My head is enfeebled and my right arm useless, and I am incapable of doing any work that involves a continuous occupation; it is forbidden me.”

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Iphigeneia in Tauris, “Leb wohl, laß dein Herz treu bewahren” (Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano; Berlin Deutsche Opera Orchestra; Heinrich Hollreiser, cond.)

Death and Funeral

Christoph Willibald Gluck’s gravestone inscription

Gluck went to the spa town of Baden, reporting that he had “once more escaped from the jaws of death, without having first recovered from my earlier illness.” In addition, Gluck was overjoyed that his Paris operas received increased performances in Vienna. Gluck himself crafted the German translations, and Mozart was said to have been a regular visitor during rehearsals of Iphigeneia in Tauris. However, in 1784, Gluck had another severe stroke.

In the last year of his life, Gluck composed a De Profundis for four-part chorus with “an optional dark-coloured accompaniment of lower strings, bassoon, horn and a trio of trombones.” On 15 November 1787, Gluck entertained two friends from Paris for lunch. Apparently, he drank several glasses of liqueur and leaving the house for a walk with his wife; he had a severe stroke in the carriage. Gluck was pronounced dead a couple hours later, and his body buried on 17 November at the cemetery at Matzleinsdorf.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter