Current research has suggested that the castrati “were considered to be a gender of their own, partly because they were not classified as male or female in society. They drifted, so to speak, in a gender limbo, often carrying a combination of male and female traits.” This assessment was frequently based on physical appearance and social behavior, with caricaturists painting castrati as huge, elongated balloons with a head and legs. Castrati “lacked an Adam’s apple, had little or no body hair, small genitalia, did not grow bald with age, lacked muscles and tended to have a distribution of body fat more like a woman. Some of them developed breasts and broad hips, and some were blessed with a skin as soft as a woman’s.” A common effect of castration was unusual tallness. Since the growth plates at the end of their bones never closed, they kept on growing. This growth was not confined to legs and arms but also resulted in larger chests, jaws, and even noses.

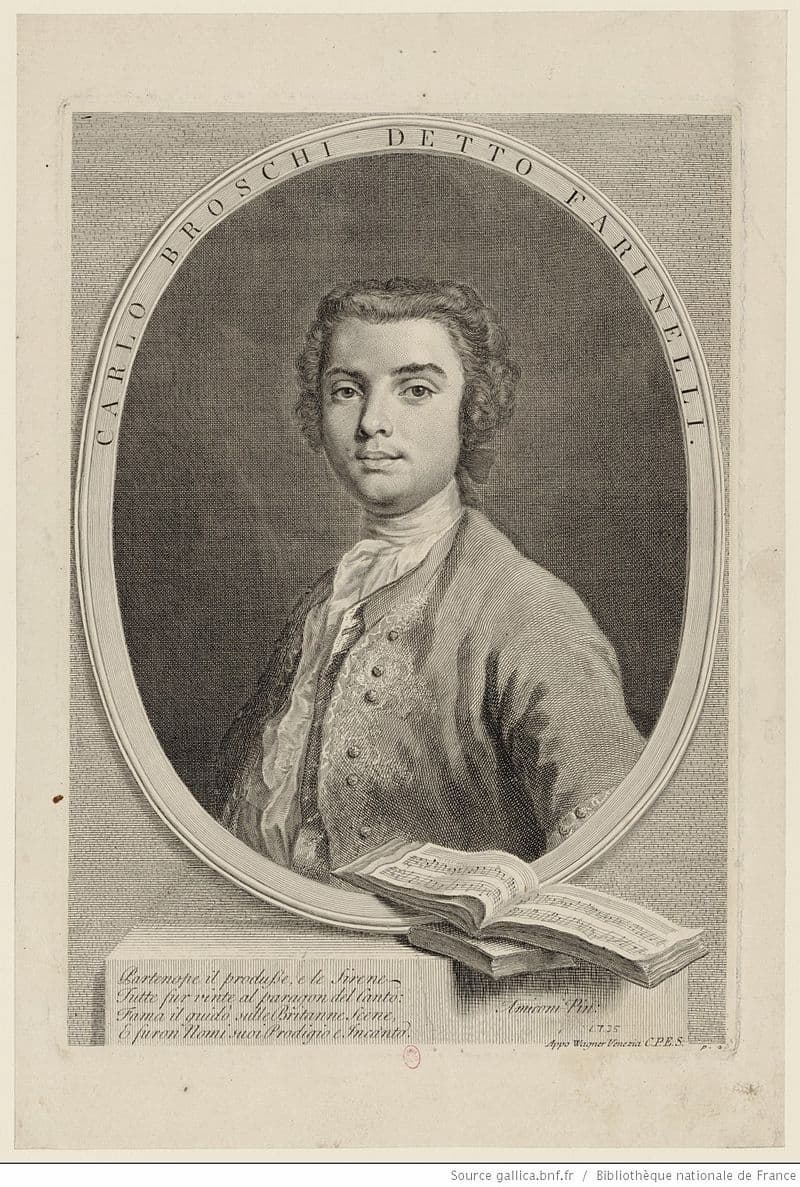

Carlo Broschi, nicknamed “Farinelli”

Physical characteristics aside, society felt uneasy dealing with castrati because of their supposed characteristic behavior. They were described as effeminate and “displayed feelings openly, something that was considered a female privilege.” A contemporary commentator wrote, “Eunuchs are an abominable tribe, who are past the sense of honour, who are neither men nor women… they are jealous, despicable, fierce, effeminate, gluttons, covetous, cruel, inconstant suspicious, furious insatiable. They cry like children if they are left out of an entertainment… The knife has made them chaste, but this chastity is of no service to them, their lust makes them furious, which yet is impotent, sterile and unfruitful.” And their connection with the theatre placed them “in a position very close to that of prostitution.”

Farinelli (Film 1994): “Ombra fedele anch’io” (Aria of Dario from opera Idaspe by Riccardo Broschi)

Carlo Broschi (1705–1782) who performed under the stage name “Farinelli” was probably the most famous castrato of all time. He must have been an exceptionally gifted singer, as his voice was considered a true wonder. “It was so perfect, so powerful, so sonorous, and so rich in its extent, both in the high and the low parts of the register. The qualities in which he excelled were the evenness of his voice, the art of swelling its sound, the portamento, the union of the registers, a surprising agility, a graceful and pathetic style, and a shake as admirable as it was rare.” The composers and theorists J.J. Quantz and W. Marpurg provided further details. “Farinelli had a penetrating, full, rich, bright and well-modulated soprano voice, whose range extended at that time from a to d3. A few years afterwards, it had extended lower by a few notes but without the loss of any high notes so that in many operas, one aria (usually an adagio) was written for him in the normal tessitura of a contralto, while his others were of soprano range. His intonation was pure, his trill beautiful, his breath control extraordinary, and his throat very agile so that he performed even the widest intervals quickly and with the greatest ease and certainty. Passagework and all varieties of melismas were of no difficulty to him. In the invention of free ornamentation in adagio he was very fertile.”

Engraving of Farinelli

These are pretty detailed descriptions by professional musicians, but can we ever really recreate the sound of Farinelli’s voice? When Farinelli became the subject of the 1994 biographical drama film, the team decided to electronically merge the soprano voice of Ewa Mallas-Godlewska with the counter-tenor of Derek Lee Ragin. Critics have suggested, “while it did capture the vocal style, the agility and the fireworks of the castrato music, the sound of the voice was not present.” Capturing his voice has become somewhat of an obsession, as Farinelli’s remains were exhumed in 2006 to examine the bones for vocal research. The research team was able to measure some bones, but rather predictably, most of the muscular structures involved in producing sound had long gone the way of the flesh.

Francesco Veracini: Adriano in Siria, “Amor dover rispetto” (Vivica Genaux, mezzo-soprano; Armonia Atenea; George Petrou, cond.)

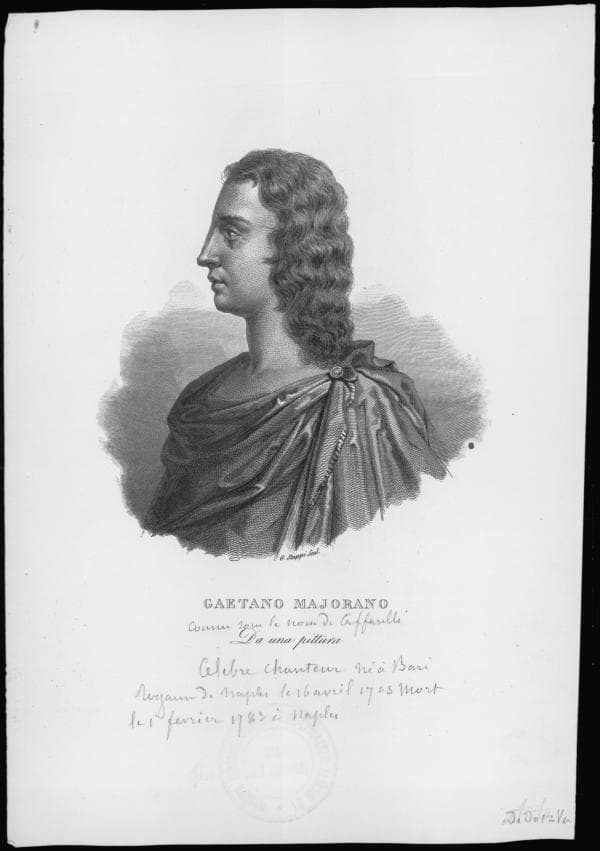

Gaetano Majorano, nicknamed “Caffarelli”

Farinelli and Caffarelli had both received the same musical education from the famed singing teacher Nicolo Porpora. However, their characters and social behavior could not have been more different. Farinelli, it was reported, “possessed a noble personality. He was measured in his words, modest by nature, and little inclined to gossip. He seemed amazed by the success he enjoyed, always considering that nothing could ever be taken for granted and that only assiduous daily practice would enable him to renew each evening the way he varied his arias. His intelligence and his sense of diplomacy gained him the loftiest social position ever attained by a castrato. During the reigns of Philip V of Spain and his successor Ferdinand VI, he became a minister and confidant of the state, living on terms of great intimacy with the Spanish royal family.”Farinelli was a legend during his life, and fictionalised accounts already appeared in the 1740s. Auber set a libretto by Scribe in the 19th century to music, and a number of novels were published in the 20th century.

Gioacchino Conti, nicknamed “Gizziello’

Nicknamed “Gizziello,” the Italian soprano castrato Gioacchino Conti was one of the greatest singers of the 18th century. He possessed an exceptionally high soprano, and he was the only castrato for whom Handel wrote a top C. Gizziello made his début in Rome in 1730, and subsequently sang in Naples, Vienna, Genoa, and Venice. One colourful anecdote relates that the castrato star Caffarelli was in the audience at a Naples performance and, full of enthusiasm, yelled, “Bravo, bravissimo Gizziello, it’s Caffariello who’s telling you.” George Frideric Handel considered Gizziello a rising genius, and he brought him to London in 1736. Gizziello made his Covent Garden début in a revival of Ariodante, and he was much admired in the press. Apparently, he was adored in every respect, “except the shape of his mouth, which made an exact square when open.” Gizziello is remembered for “choosing to sing in a fluent and smooth style of rendering and expression. Rather than abusing coloratura, he remained famous as a sentimental and gentle singer.”

George Frideric Handel: Atalanta, “Non sara poco” (Susanne Rydén, soprano; Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci

The Italian soprano castrato and composer Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci was born in Siena and trained at the Naples Conservatory. He first appeared on the Venetian stage and was subsequently active at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Like a good many of his colleagues, he visited London and was first heard at the King’s Theatre in 1758. After spending some time in debtors prison, he made friends with Johann Christian Bach and sang the title role in his new opera Adriano in Siria. Tenducci also performed in Ireland, and in 1766, he secretly married the 15-year-old Dorothea Maunsell, the daughter of a Dublin lawyer. This secrecy is understandable, as a castrato was forbidden to marry in Italy. His wife had two children that Tenducci recognized as his own.

The curious fact of a castrato siring children was explained to Casanova “Nature had made him a monster that he might remain a man; he was born triorchis, and as only two of the seminal glands had been destroyed, the remaining one was sufficient to endow him with virility.” That particular claim remained uncorroborated, and it has been suggested that the children may have been the children of Dorothea’s second husband. At any rate, during his marriage, Tenducci was severely persecuted by his wife’s family, and when she wanted to marry another man, he was put on trial for impotency. Tenducci returned to London, where he remained for almost the rest of his life. His voice was described as particularly lyrical, and he was widely known as another Senesino. By sheer coincidence, Tenducci was in Paris during Mozart’s visit in 1777/78. He gave Mozart singing lessons, and impressed with his teacher’s abilities, Mozart wrote a concert aria for him, which has sadly been lost.

Johann Christian Bach: Adriano in Siria, “Cara, la dolce fiamma” (Philippe Jaroussky, counter-tenor; Le Cercle de l’Harmonie; Jérémie Rhorer, cond.)

Giovanni Battista Velluti

During the middle decades of the 17th century, the number of active castrati may have reached several hundred. Changing vocal ideals aside, the practice of castration for musical purposes was increasingly attacked, even in Italy. When castration ceased to be an option for poor Italian families, other survival strategies were adopted. However, the reason for the downfall of the castrato is found in the music itself. “The sound of opera in the 18th century featured many high and comparatively few low voices. When ensembles gained popularity on stage, audiences demanded a more balanced sound, with evenly distributed voices that spanned a greater range of the sound spectrum.” While only the Papal States, and subsequently the Vatican, went on making and employing a small number of castrato church singers, Giovanni Battista Velluti (1780-1861) was the last of the great operatic castrati. And for the last decade of his career, he was without a rival.

He created a substantial number of operatic roles, including “Arsace” in Rossini’s Aureliano in Palmira, and “Vitekindo” in Nicolini’s Carlo Magno in Piacenza. His favorite role during the final decade of his operatic career was “Tebaldo,” in Morlacchi’s Tebaldo e Isolina, and let’s not forget “Alceo” in Rossini’s Il Vero Omaggio. At the height of his career, he created “Armando” in Meyerbeer’s Il crociato in Egitto. Like countless colleagues before, Velluti made his way to London. Enthusiastically supported by the Duke of Wellington, he gave his début in 1825 in Il crociato in Egitto. The audience laughed at him, and his appearance caused a storm in the press. The golden age of the castrato had clearly passed, but Velluti’s “manner of dramatic interpretation was adopted by the great female singers of the 1830s and 40s, including Pasta, Malibran, Pisaroni, and Persiani.” Castration, for primarily a number of disgusting reasons, was and is still practiced today, but for purely musical purposes, we rightfully consider it an atrocity of the past.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Giacomo Meyerbeer: Il crociato in Egitto, “Il di renascera” (Michael Maniaci, counter-tenor; Teatro la Fenice Orchestra; Emmanuel Villaume, cond.)