Claude Debussy set altogether thirteen poems by the Parnassian poet Théodore de Banville (1823-1891). The Banville mélodies, like almost half of his entire output for voice and piano, date from a period between roughly 1880 to 1884. This period was permeated by four experiences that greatly shaped Debussy’s personal and musical development.

For one, Debussy began his Conservatoire training in composition and received the Prix de Rome in 1884. Furthermore, during the summers of 1880 through 1882, he traveled throughout Europe and Russia as pianist for Nadezhda von Meck, the celebrated patron of Tchaikovsky.

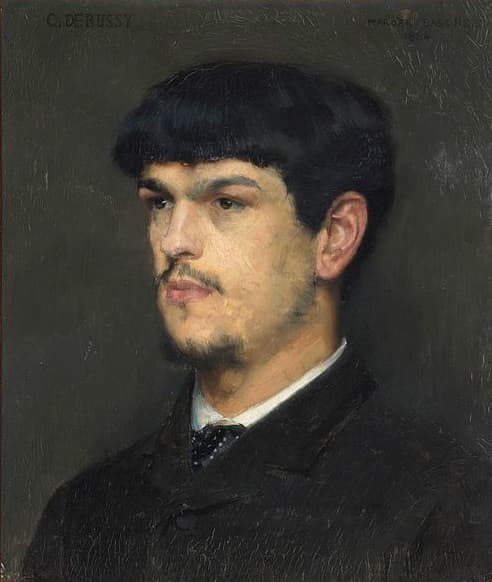

Claude Debussy by Marcel Baschet, 1884

Debussy first studied Wagner’s Tristan in 1882, and he met the Vasnier family in 1880. The composer got his first real lessons in love from Marie-Blanche Vasnier, an amateur soprano married to a Parisian civil servant. She guided him in his choice of clothes and through the world of literature, inspiring a substantial number of love songs. To celebrate Debussy’s birthday on 22 August we decided to feature some of the delightful Banville settings by the emerging composer.

Claude Debussy: “Nuit D’étoiles”

Théodore de Banville

Théodore de Banville

During his studies at the Paris Conservatoire, Debussy was observed walking around the institution with a volume of Banville in his hands. But who was Théodore de Banville (1823-1891)? He was certainly a prolific poet, dramatist, critic and prose fiction writer whose contribution to the poetic and aesthetic debates in nineteenth-century France has long been overlooked.

Banville exerted a profound influence on major writers such as Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine and Mallarmé, but critics “dismissed his formal pyrotechnics, effervescent rhythms and extravagant rhymes as mere clowning.” He originally studied law but quickly turned to poetry, publishing his first collection Les Cariatides in 1841. In quick succession, he published 16 additional collections of poems, the last issued in the year after his death in 1891.

Banville actively participated in the intellectual and artistic currents of his time as a journalist and critic. He contributed to twenty-four journals and wrote nineteen theatrical works. In addition, he wrote a number of novels, tales, and prose works about his voyages, memoirs, and portraits.

Claude Debussy: “Rêverie” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

Les Cariatides (The Cariatides)

Banville’s Les Cariatides, 1889

Banville compiled a selection of verses published under the title Les Cariatides (The Cariatides) between the ages of sixteen and nineteen. The title of the collection comes from Greek mythology and refers to the sculptured columns in the shape of women that support the temple of Apollo. This initial collection was dedicated to his mother.

The idea for this collection of poems was derived from a painting of a French sculptor and painter, Edmé Bouchardon (1698-1762), whose images Banville attempted to translate into poetic words. In these early lyrical poems, Banville describes the physical beauty and grace of these figures rather than expressing emotions such as passionate torments or desperate invocations.

“Rêverie”

The gentle breath of the zephyr

Opens the wild roses,

And makes everything fertile

On mountain and plain.

The lily and the red vervain

Fall flowering from its fingers,

His brimming cup causes all things to open,

And everyone quivers at his voice.

But one fragile plant

Withdraws and flees trembling

From the kiss that will bruise it.

I know of some plaintive souls

That resemble mimosas

And who die from happiness

Claude Debussy: “Pierrot” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

Commedia dell’arte

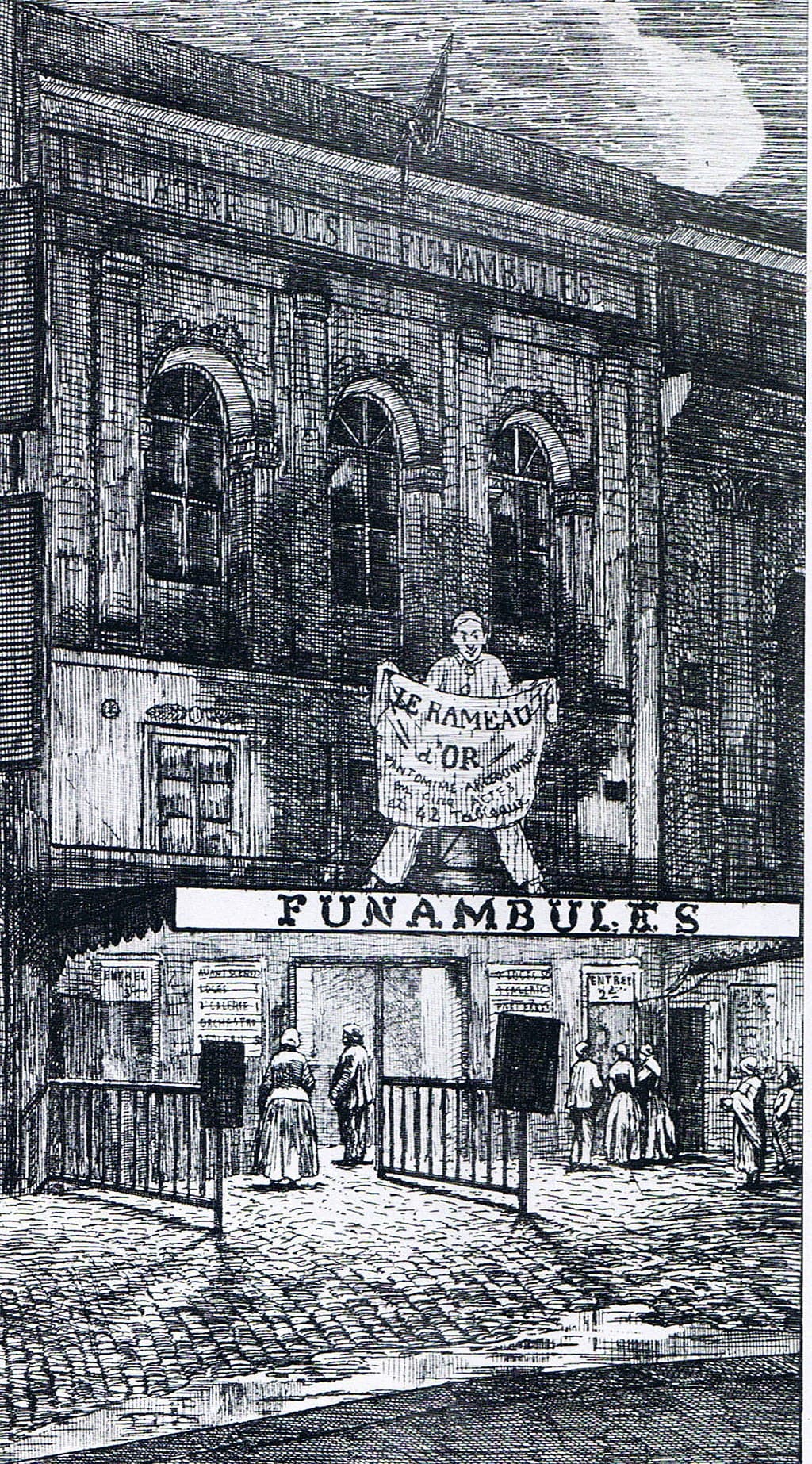

Théâtre des Funambules in its last year on the Boulevard du Temple, c. 1862

Banville enjoyed a rather idyllic childhood, and many of his earliest memories are reflected in this volume. Contrary to most other French poets, Banville actually loved music, and his verses show great musicality. Banville also enjoyed the theatre, spending much time during his youth at the Théâtre des Funambules.

In that theater, he saw the famous French mime Jean Gaspard Debureau who acted the part of Pierrot, and Banville later wrote the poem “Pierrot” from his earliest memories. Théâtre des Funambules was located on the Boulevard du Temple, and the name of the street and the mime are scripted in the poem.

“Pierrot”

Good old Pierrot, watched by the crowd,

having done with Harlequin’s wedding,

drifts dreamily along the boulevard of the Temple.

A girl in a flowing blouse

vainly leads him on with her teasing eyes;

and meanwhile, mysterious and sleek,

cherishing him above all else,

the white moon with horns like a bull

ogles her friend

Jean Gaspard Deburau.

Claude Debussy: “Fête galante” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

Fête galante

Antoine Watteau’s Fête galante paintings

Banville was greatly inspired by Jean-Antoine Watteau, one of the most original and brilliant artists of the eighteenth century. Watteau had a lasting impact on the development of Rococo art in France and throughout Europe. His sensuously painted idylls “conveyed courtly love and ideas of reverie, longing, and utopia at a time of aristocratic indulgence and hedonism.” In fact, his depiction of elegantly dressed aristocrats flirting in the landscape, essentially a stage-like setting within a naturalistic panoramic scene, established a brand-new genre called “fête galantes.”

One of the first poets to discover Watteau, Banville used the paintings as the source of inspiration for his poems and prose.

“Fête galante”

Behold Silvandre and Lycas and Myrtil—

There’s a celebration tonight chez Cydalise.

A subtle perfume pervades the air;

In the vast park, where all is perfection,

Aminta rivals the rose.

Phyllis and Eglia, following their lovers,

Seek shade in a thousand charming places;

Beneath the inflaming and glittering sun,

Proudly vying with diamonds,

The white peacock spreads its tail on their path.

Debussy’s setting does not feature Wagner‘s wandering chromaticism but instead focuses on melodic inflections. As Debussy related, “chromatic bridge passages submerge the tonality.” As a scholar writes, “The choice of the Dorian mode, a flute-like, arabesque melody, and quasi-modal chord successions by second and third subtly evoke the unreal world of Banville’s poem and reflect a common inspiration by Watteau.”

Claude Debussy: “Caprice” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

Mme. Vasnier

Portrait of Madame Vasnier by Jacques Emile Blanche

Paul Vidal, a contemporary of Debussy at the Conservatoire described Mme. Vasnier as “a pretty woman, she is adoringly pursued, which sustains her dear vanity; a singer of talent, she interprets Debussy’s works in a superior manner, and all that he writes is for her and because of her.” Between 1880 and 1884, Debussy composed some twenty-four melodies for Mme. Vasnier, and he accompanied her in the Parisian salons and in public.

Biographers speak of “Debussy’s first great love,” and the relationship was certainly important for the young composer. Dedication on a number of song manuscripts speaks for the Naïveté of the relationship as Debussy writes, “these songs that have lived only through her and will lose their charm if ever they cease to pass through her melodious fairy-like lips.” In the event, Debussy set Banville’s poem “Caprice” a few weeks after he first met Madame Vasnier.

“Caprice”

When I kiss, pale with fever,

Your lips where a song springs,

You turn away your eyes, your lips

Remain cold as ice,

And, thrusting me away from your arms,

You say I do not love you.

But if I say: this long martyrdom

Has destroyed me, I break my bonds!

You answer with a smile:

Come to my feet! You know full well,

My dear soul, that it is your fate

To adore me until death.

Claude Debussy: Hymnis, “Il dort encore” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martiineau, piano)

Il dort encore

Théodore de Banville’s Hymnis, 1880

Debussy also found inspiration in Banville’s play Hymnis. It was first performed at the Théâtre Nouveau Lyrique in Paris in 1879 and published the following year. Debussy composed a piece with the same title for voice, chorus, and orchestra in 1882, but it remained unpublished. The version for solo voice and piano from the first scene was first published in a collection titled “Sept Poémes de Banville: pour soprano léger et piano.”

The setting apparently reflects the vocal capabilities of Madame Vasnier to whom it is dedicated. A scholar has drawn parallels between her and the maternal, protective, but passionate Hymnis seeing in her beloved a reflection of Debussy himself.”

“He is still sleeping”

He sleeps again one hand on the lyre!

He sees neither my delirious sadness

Nor these drawn out tears which fall from my eyes

Divine charmer, while you nap,

Around you flit bees.

The sweet poet is the messenger from God!

The wandering white star of the skies loves you.

Close your delighted eyes, nap again,

Anacreon, melodious singer.

While flees the charming night,

Let’s a happy rhythm cradle you and touch you,

The sweet poet is the messenger from God!

Claude Debussy: “Le Lilas” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

Banville Mélodies

In his Banville settings, Debussy carefully mirrored the poetic rhyme scheme through his use of rhythm and cadence. Banville generated patterns of intonation and rhythmic effects by alternating masculine and feminine rhyme words. In turn, Debussy set masculine rhymes on the strong beat, creating a swift and abrupt temper, while feminine rhythms created fluid sounds on the weak beats.

The young composer skillfully transformed poetic nances into musical expression by using pentatonic pitch collections in both piano and voice. As a scholar writes, “Debussy thus creates a dreamy or exotic atmosphere and unites the poetic theme through the song.” That particular atmosphere and poetic mood are established by extended piano preludes, and off-tonic beginnings often generate a sense of vagueness and anxiety.

It has been suggested that “Debussy’s musical illustrations are accomplished by inserting compositional techniques such as a dissonant chord, an unexpected harmonic shift, ornaments, trills, or a new motive to highlight the changes of emotions, character’s images or sudden behaviour. The wordless melismas at the ends of Debussy’s early songs provide listeners with lingering imagery and emotional resonance of the poetry.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Claude Debussy: “Souhait” (Jennifer France, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

Pity not all the songs were in their original language.