The legendary pianist and pedagogue Heinrich Neuhaus (1888-1964) stood at the centre of a dynasty of Russian pianism that still continues to reverberate today. Known as “Heinrich the Great,” his name alone transcended musical circles as he became a national cultural icon and household name.

Heinrich Neuhaus

He was one of the most charismatic and sought-after pianist-pedagogues of the twentieth century, and his name “is inseparable from the successes of the Soviet Piano School.” It has been said that as “a central pillar of the Moscow Conservatoire piano department, he directly or indirectly shaped and polished all the major Russian stars of the last half-century,” with his students passing on his legacy to subsequent generations.

We thought it might be fun to look at some of the most brilliant pianists that passed through the hands of Heinrich Neuhaus and to explore his fundamental approach to playing the piano and to interpretation.

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Chopin’s Nocturne in F-sharp, Op. 15, No. 2

The Art of Piano Playing

We are very fortunate that Heinrich Neuhaus recorded his thoughts, ideas, and principles in his book The Art of Piano Playing, first published in 1967. Even today, a good many teachers around the world regard this book as the most authoritative source on the subject of playing the piano.

Heinrich Neuhaus: The Art of Playing the Piano

Neuhaus introduces his thoughts with a few simple opening statements. As he writes, “before beginning to learn an instrument, the student spiritually must be in possession of some music.” Even before he touches a keyboard or draws a bow across the string, “he has to carry in his mind, keep in his heart, and hear music in his mind’s ear.” I guess Neuhaus means natural predisposition and talent.

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Mozart’s Rondo, K. 511

Performance and Technique

Heinrich Neuhaus teaching

For Neuhaus, “every performance consists of three fundamental elements; the work performed (the music), the performer, and the instrument. Only the complete mastery of these three elements can ensure good artistic performance.” According to Neuhaus, teaching should never be channeled in one or the other direction “since one of the three elements is bound to suffer.” Essentially, this will result in imperfect playing tainted by amateurism.

Neuhaus goes on to talk in great length about technique, which is simply the means of attaining the content, music, and perfection of performance. “My method of teaching,” he writes, “consists of ensuring that the player should as early as possible grasp the artistic image, that is, the content, meaning, the poetic substance, the essence of the music, and be able to understand thoroughly in terms of the theory of music, what it is he is dealing with.”

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in G-sharp minor (WTC I)

Work Ethic

As Neuhaus continues, “a clear understanding of this goal enables the player to strive for it, to attain it and embody it in his performance; and that is what technique is about. The trouble is that many who play the piano take the word technique to mean only velocity, evenness, and bravura, sometimes meaning flashing and bashing. Such qualities in themselves do not ensure an artistic performance.”

According to Neuhaus, “for very gifted people it is difficult to draw a distinction between work at technique and work at music, even if they happen to repeat the same passage a hundred times.” Repetition, for Neuhaus, was the mother of tuition, useful for the weakest as well as the strongest talents. “Mastery of the art of working, one of the reliable criteria of a pianist’s maturity, is characterised by an unwavering determination and an ability not to waste time.”

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Shostakovich’s 13 Preludes from Op. 34

Interpretation

Neuhaus strongly believed that for the formation of the artist, the first prerequisite is “the improvement of the human being.” He believed that art was ultimately a reflection of the activities of humankind and that the performance of music was a philosophical act capable of defining the self. Neuhaus grew up in an environment that questioned the relationship between the pianist-composer and the pianist-interpreter. He made the conscious decision to become a pianist, and to forgo composition.

Neuhaus positioned himself as an interpreter of other people’s works, and specifically as an explorer of the “composer’s emotional world.” As Neuhaus writes, “The goal of emotive art is first and foremost the creation, on stage, of a living life of the human soul and reflection of that life in the artistic stage form. This life of the human soul is created through the truthful, sincere feeling and sincere passion of the artist.” And now it’s time to have a look at some of the brilliant pianists who counted themselves among Heinrich Neuhaus’ students.

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Scriabin’s 5 Preludes from Opus 11

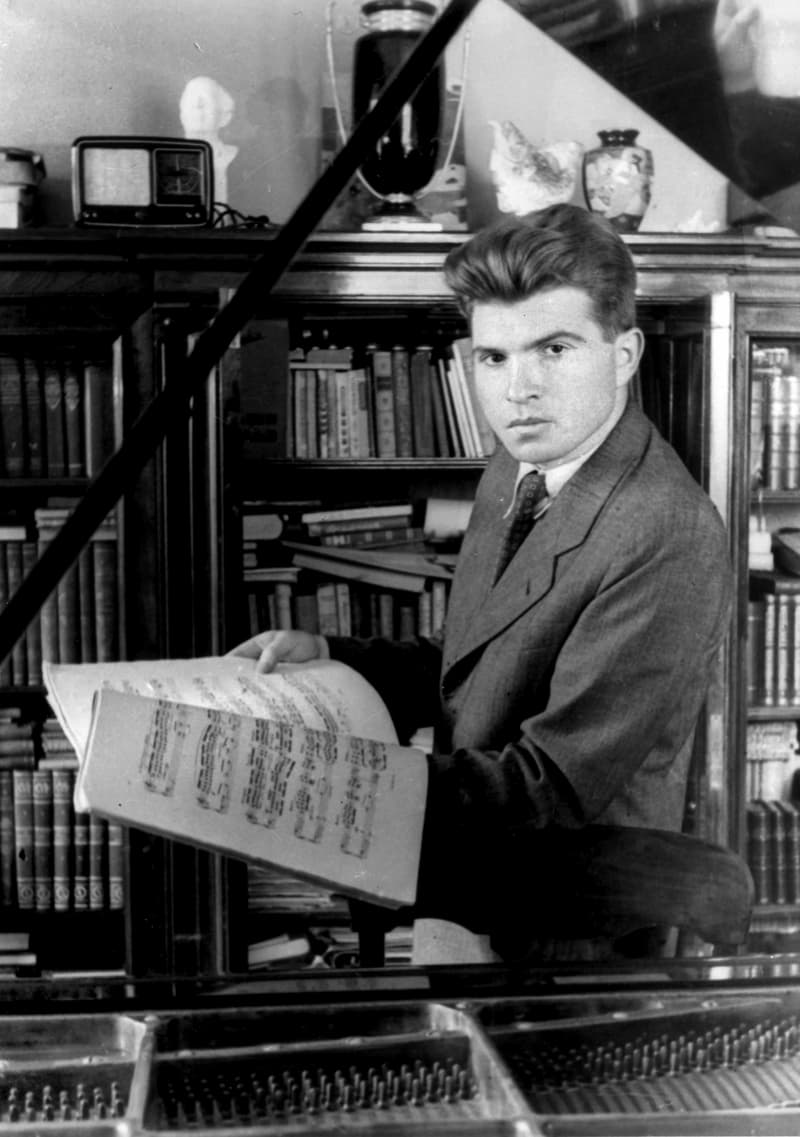

Sviatoslav Richter

It’s probably fitting to start with Sviatoslav Richter (1915-1996), widely considered one of the greatest pianists of all time. Richter decided to attend a masterclass Neuhaus was giving in Odessa and auditioned with the 4th Chopin Ballade in 1937. Neuhaus remembered, “So there he comes, a tall, skinny youth, fair hair, blue eyes, lively and amazingly attractive features. He sits down at the grand piano, puts his large, soft, and nervous hands to the keys, and plays with accentuating simplicity and austerity. His performance immediately captured me with perplexing penetration into the music, I think, he is a genius musician.”

Sviatoslav Richter

Richter was admitted to the class of Heinrich Neuhaus and to his home. In Neuhaus, Richter found his ideal teacher, and Neuhaus recalled that Richter treated each composition like a vast landscape, which he surveyed from great height with the vision of an eagle, taking in the whole and all the details at the same time. “He played like no one I had ever heard, and there was nothing I could teach him.” Well, not entirely it seems, as Richter viewed Neuhaus as his idol, “a strikingly generous soul, and part of a vast literary, philosophical and artistic culture.” And as Richter often repeated, “It was in tone production, that my teacher freed up my playing.”

Sviatoslav Richter Plays Chopin’s Etudes Op. 10 & 25

Emil Gilels

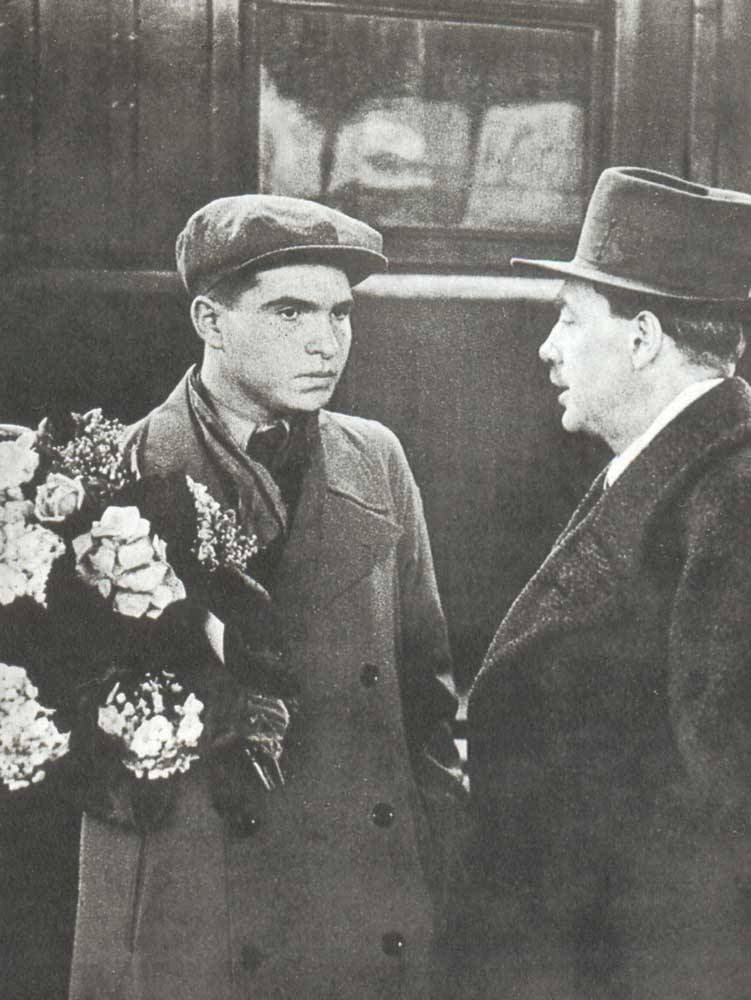

Gilels and Neuhaus

The second huge name associated with Heinrich Neuhaus was Odessa-born Emil Gilels (1916-1985), but that particular student-teacher relationship was not an easy one. Gilels had graduated from the Odessa Conservatory in the autumn of 1935 and was accepted into the class of Heinrich Neuhaus as a postgraduate student at the Moscow Conservatory. Gilels had earlier played for Neuhaus at the age of 16, but the prominent piano professor only saw empty virtuosity. Gilels won the First All-Union Competition in 1933 and subsequently embarked on an extensive concert tour around the USSR. Already a competition winner and famous musician in his own right, Gilels started his studies with Neuhaus.

Emil Gilels, 1940

Gilels was an exceptionally modest, shy, and self-critical pianist, and Neuhaus saw him foremost as a virtuoso who was in dire need of working at the musicality and the general understanding of music. There are reports that Neuhaus was happy to point out Gilels’ minor faults, as he felt it necessary to make sure that the young pianist did not become complacent. To be sure, Gilels did not receive the kind of encouragement and heartfelt guidance that he desperately needed. Gilels studied with Neuhaus for two years, and according to the rising pianist, “all Neuhaus did was polish my playing a bit, but he was no great influence on me. He was a good speaker but his playing was spotty. Of course, he was a big authority in music, but in terms of birth, I was born from other professors.”

Emil Gilels Plays Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 28, Op. 101

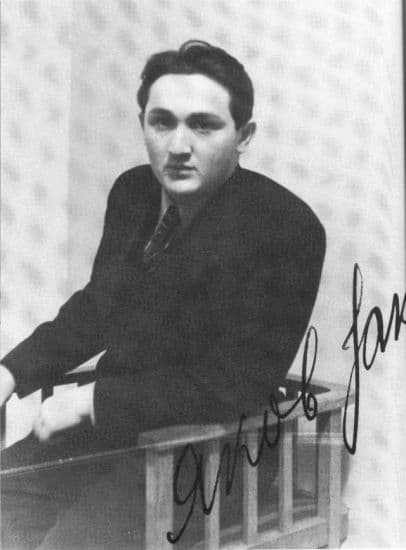

Yakov Zak

Yakov Zak

Yakov Zak (1913-1976) also hailed from Odessa, and initially was a classmate of Gilels in Moscow. Zak formed a piano duet with Gilels and several of their recordings are still available. Zak was one of several exceptionally gifted pianists emerging in the 1930s, and he was also erudite in literature and philosophy, and a great connoisseur of painting. He was renowned for his visual, colourist approach to music and, in his own teaching, modelled on Neuhaus, made frequent comparisons between the art of painters and elements of form and musical interpretation. Zak received his pianistic grounding at the Odessa Conservatoire, and by 1932 was enrolled at the Moscow Conservatoire to complete his studies under Heinrich Neuhaus.

Zak graduated in 1935 and took 3rd prize in the All-Soviet Musical Performance Competition in Moscow. Only two years later Zak was the winner of the 3rd Chopin Competition in Warsaw, and in the same year was appointed a colleague of Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory. Neuhaus ranked Zak among the finest pianists of his generation, praising his “combination of clear, powerful intellect, a rigorously organised temperament and tremendous inner energy with a penetrating sensibility and admirably controlled virtuosity.”

Yakov Zak Plays Prokofiev’s Toccata

Vera Razumovskaya

When Vera Razumovskya (1904-1967) first stepped into the Neuhaus studio, he asked her to play a C-major scale in the right hand with a “quiet, divine sound in ideal legato, and to accompany it with light chords in the left.” Bach was for Neuhaus a pedagogical staple and source of personal ritual training a pianistic attitude to sound. All Neuhaus students talked about Neuhaus demonstrating voicing of polyphonic textures in Bach, especially in the context of an ideal legato produced by the fingers as well as the pedals.

Vera Razumovskaya

Razumovskaya studied with Heinrich Neuhaus at the Kiev Conservatory, and she started to teach at the Leningrad Conservatory only a couple of years after graduation. Razumovskaya was one of a number of students who carried on the Neuhaus legacy through her own teaching. Following in the footsteps of her famous teacher, Razumovskaya considered the interpreter “as someone who does not only interpret music but whether he wants it or not, involuntarily reveals himself in the music; he offers his portrait.”

Vera Razumovskaya Plays Schumann’s Fantasie, Op. 17

The Three Bogatyrs

By the 1950s, Neuhaus entrusted the main preparation of his students to his assistants, his son Stanislav Neuhaus, Yevgeny Malini and Lev Naumov (1925-2005). The most important aspect of the Neuhaus teaching legacy was the ability to produce a “noble” sound on the piano, without unduly percussive “banging.” Naumov recalled that “at least three-quarters of the time, Neuhaus devoted to working on sound.” Neuhaus also spent an extraordinary amount of time to help structure, focus, and deepen the appreciation of a work’s interpretation. Naumov reports, “every measure needed analysis and was edited, and sometimes we spent a long time on one note or chord.”

According to Naumov, Neuhaus did undergo volatile changes of mood that could make lessons a terrifying experience “as his charm suddenly gave way to his fiery temperament.” On one unfortunate day, “when the alignment of the stars had cast a shadow on the lesson on a talented but lazy student who continually made the same mistake, an enraged Neuhaus threw a cast-iron ashtray at him. He later qualified his action with the words: But you all saw, I did try to miss!”

Stanislav Neuhaus Plays Chopin’s Ballade No. 4 in F minor, Op. 52

Eliso Virsaladze

Eliso Virsaladze (1942-) was born into a musical family in Tbilsi, and she studied piano with her grandmother, a student of Anna Esipova. Once she had graduated from the Tbilisi State Conservatory, she continued her postgraduate studies at the Moscow Conservatory. Officially, she studied with Yakov Zak, but frequently played for Heinrich Neuhaus as well. She recalls, “I was admitted to the class of the famous Professor Heinrich Neuhaus. He was a good friend of Granny’s, she wrote him, that I was on my way, but he never patronized any of his students.”

Eliso Virsaladze

“Everyone in his class was top-notch,” she recalled, “so I had to work real hard not to fall behind. Neuhaus never left anything to chance and was always attentive to detail to make sure we played like no one else did. He was also entirely devoted to his profession and his devotion certainly brushed off on us. It surely did on me and it helped me a lot in my future work both on stage and as a teacher.” Virsaladze did win the third prize in the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1962, and the first prize in the Schumann Competition in Zwickau in 1966. To this day considers Neuhaus both her pedagogue and mentor.

The list of exceptional pianists who passed through the hand of Heinrich Neuhaus is simply unbelievable. My sincere apologies to Anton Ginsburg, Vera Gornostayeva, Vladimir Krainev, Alexei Lubimov, Nina Svetlanova, Igor Zhukov and Elena Richter, to only name a selected few, for not having enough space to feature them all in great detail. Through his recordings, writings and his teaching, Heinrich Neuhaus left an enduring legacy that is of lasting consequence to anybody serious about learning to play the piano.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Gilels resented Neuhaus, and wrote a bitter letter to him reminding him that his true teacher was the one he had in Odessa, Bertha Reingbald. I learned from my former teacher, a student of Samuel Feinberg. Neuhaus was not a good colleague, with an obnoxious personality, who did not waste any opportunity to put others down. He was perhaps a great performing theorist, but his playing is indicative of technical limitations….