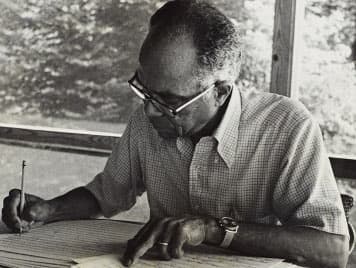

American composer Ulysses Kay (1917–1995) studied with Paul Hindemith at Tanglewood and Yale and, following WWII, With Otto Leuning at Columbia. From 1946 to 1952, he was in Rome, having won the Prix de Rome not once but two times in a row. Instead of going into teaching, he worked for BMI, the performing rights organization, first as an editorial advisor and then as a music consultant. While there, he was appointed by the US State Department to be part of a delegation travelling to the Soviet Union to meet Soviet composers. The group’s 30-day tour took them to Leningrad, Moscow, Kiev in Ukraine, and Tbilisi in Georgia. In 1968, Kay joined the faculty at Lehman College, CUNY, where he taught for the next two decades.

Ulysses Kay

Kay’s Concerto for Orchestra was composed in 1948, at a point where the post-war composers were deciding on new directions: the avant-garde and experimental (Messiaen and Boulez), stochasticism (Xenakis), just pure experimentalism (Cage). Composers went beyond playing with melody and harmony to exploring timbre, texture, rhythm, and the other basic elements of music. The split affected audiences, too, who had an increasingly difficult time following composers down the path of music, as there was no longer a shared language.

In American music since the 1920s, popular music, such as jazz, was making its influence felt on classical music. The inclusion of African American music outside of jazz was also a possibility.

Luckily, neo-classicism became a saving grace for both composers and audiences. Starting with Les Six in France, who chose not to follow the path of the Second Viennese School into atonality, 12-tone music, and serialism, neo-classicism permitted composers to use 17th- and 18th-century genres and similarly old forms and techniques to give their use of a distinctly modern harmonic system a basis for development. Avoiding the excess of Romanticism and using the elements of music and musical form gave modern composers a way to move forward and bring their audiences with them.

Where a Baroque concerto might set a small group of instruments and a traditional concerto sets a single instrument against the orchestra, a concerto for orchestra permits the composer to use many instruments as a soloist. In Kay’s Concerto for Orchestra, by contrast to both Baroque and traditional styles, he uses families of instruments (brass, woodwinds, and strings) as his soloists, using their differing timbres as their solo voices. In addition, he uses texture as a point of contrast.

The fast opening starts this process with the strings at the fore.

Ulysses Kay: Concerto for Orchestra – I. Toccata: Allegro moderato (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Kellen Gray, cond.)

The second movement starts with the woodwinds, first clarinets, then flutes. The strings enter next, countering the woodwinds. Each family of the orchestra has a role and has its own section of the movement. After a brass chorale-like section and a climax on a dissonant chord, the orchestra drops out, and we finish as we begin: woodwinds and strings.

Ulysses Kay: Concerto for Orchestra – II. Arioso: Adagio (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Kellen Gray, cond.)

Taking his final movement from a 17th-century Baroque bass pattern, the passacaglia, Kay constructs a variation movement, again contrasting families of instruments. After the introduction, each variation builds until, by the end of the 2nd variation, the full orchestra has entered and builds to a brief climax. The next variation begins with the woodwinds, then the brass, starting with the French horn, announces the final variation. He builds with counterpoint that becomes increasingly dense in texture and dissonant in harmony until the brilliant brass conclusion.

Ulysses Kay: Concerto for Orchestra – III. Passacaglia: Andante (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Kellen Gray, cond.)

When you contrast this work with Bartók’s written just 5 years earlier, we can see how Kay’s use of families of instruments, rather than sections of instruments, gives this concerto for orchestra a more unified feel. By contrasting larger but similarly sounding groups, Kay gives himself a larger soloist force – it can be broken down into individual kinds of instruments or used en masse. The use of neo-Classical style makes it both accessible and modern for the listener.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter