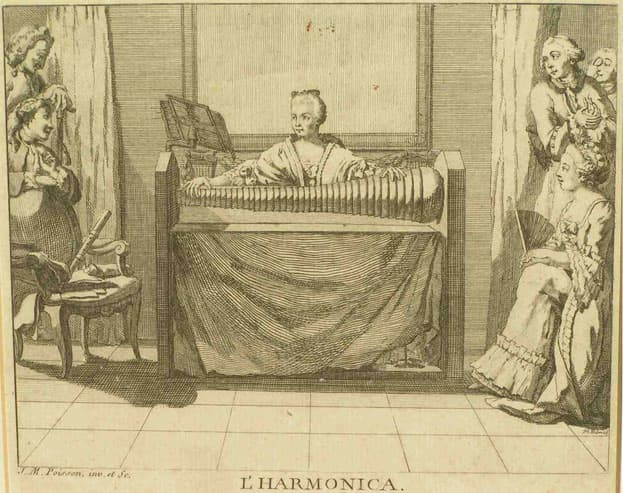

A blind woman steps on a Viennese stage and makes her way to a strange new instrument called the glass harmonica. The sounds it makes are whistle-like and otherworldly. (Eventually, rumors would circulate that playing it or even hearing it could cause a person to go mad. Some sources went so far as saying that playing it ultimately killed her!)

Marianne Kirchgessner

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, a few months away from dying, is in the audience. He’s entranced – and he writes his last piece of chamber music specifically for her.

Today we’re looking at the remarkable story of glass harmonica virtuoso Marianne Kirchgessner. Here are thirteen facts about her life:

1. Marianne Kirchgessner was born in Bruchsal, Germany, in June of 1769, the fifth of seven children. Her parents were both musical: her father was a cellist and her mother was a pianist.

2. When Marianne was four years old, her mother died. Soon after, little Marianne came down with smallpox and lost her sight. Around the same time, despite her blindness, she began teaching herself keyboard.

3. Eventually she began studying an instrument known as the glass harmonica with a conductor named Joseph Schmittbauer…who also happened to run a glass harmonica factory in Karlsruhe.

4. The glass harmonica was a unique musical instrument that was invented by Benjamin Franklin in 1761, consisting of glass bowls mounted on an iron spindle and operated via a foot pedal and the players’ wet fingers. Kirchgessner became one of the primary exponents of this niche instrument, which enjoyed a surge of possibility in the late eighteenth century.

5. Kirchgessner was so talented, that it was decided that she should go on tour. Despite the difficulties of traveling by carriage in the eighteenth century, especially while blind, she embarked on what would become years of travel when she was just a young woman, and she became a phenomenon across Europe.

Glass harmonica

6. She traveled with a man named Heinrich Philipp Bossler and his wife. Bossler was an intriguing figure: he was a manager, a publisher, and a music critic. He published important early works by giants like Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart. He also was unusually principled among music publishers of the time in that he refused to publish plagiarized music (other music publishers of the time had no such scruples). The Bosslers became Kirchgessner’s adopted family, and they traveled across Europe together.

7. When she came to Vienna, Mozart was so taken by Kirchgessner’s playing that he wrote this haunting Adagio and Rondo for her in 1791. She premiered it that summer and the performance was advertised as featuring Mozart himself. Mozart would die before the year was out, making this the last chamber music piece he ever wrote, and one of the last performances he ever took part in.

Wolfgang A. MOZART Adagio und Rondo für Glasharmonika, Flöte, Oboe, Viola, Violoncello, KV 617

8. He also wrote the Adagio for Glass Harmonica in C major, K 356 or 617a to her. It’s truly mystical and sounds unlike anything else he ever wrote.

Adagio for Glass Harmonica in C major, K 356 or 617a By Mozart

9. After her appearances in Vienna, she traveled throughout Germany and Bohemia, causing a stir wherever she went. She was so admired by the Berlin court that she played for King Friedrich Wilhelm II multiple times.

10. In 1794 she crossed paths with Haydn in London, appearing as a soloist in his concert series. Apparently, he also wrote a solo piece for her, but the score has been lost, possibly in part because she didn’t require traditional manuscript scores to learn new music.

11. While in London, she had a mechanic build her a new instrument, which became her favored one, and from then on, she traveled with it wherever she went on tour. It would have been extremely bulky and must have been very difficult to travel with!

12. In the summer of 1808, a highlight of her life of travel occurred when she met with German poet and playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in Carlsbad.

13. In the winter of 1808, after her first Swiss tour, she decided to take a detour to visit a sibling in Odenheim, Germany. On the route, she came down with pneumonia and developed such a high fever that she began hallucinating. To the deep grief of the Bosslers, her faithful traveling companions who stayed with her until the end, she died on 9 December 1808 at the age of thirty-nine. Her final words were “Beautiful! Very beautiful!”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter