This very first production of Eduardo e Cristina at the Rossini Opera Festival (ROF) completes the performed oeuvre of the great Pesarese maestro. The epicentre of Rossiniana possibly left it so late because of the challenges of this barely performed piece which first saw the light of day in 1819, and enjoyed a bit of success before completely falling out of the operatic repertoire.

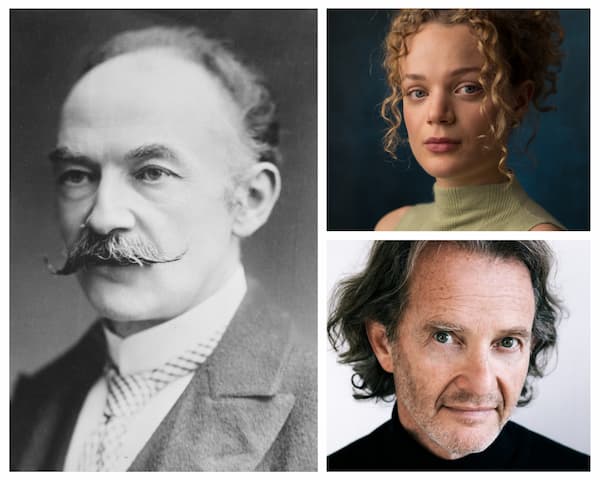

Daniella Barcellona (Eduardo), Anastasia Bartoli (Cristina) © Rossini Opera Festival | Amati Bacciardi

Rossini’s score has been criticized as a cut-and-paste from other works of the great composer. But this very fact makes it particularly accessible as it draws on familiar material from Ermione, Aureliano in Palmyra, Barbiere di Siviglia, and especially from Adelaide di Borgogna (the latter being showcased in a new ROF production in this same season). The new critical edition by the ROF allowed the conductor Jader Bignamini and the fully staffed Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI to showcase the rich melodic tapestry.

Anastasia Bartoli, in her ROF debut, deployed her luscious soprano as Cristina, though one suspects her voice is more suited for Verdian and Puccinian territory. She was matched with festival veteran Daniela Barcellona in the trousers role of Eduardo. The first act duet In que’ soavi sguardi showed what these two artists are vocally capable of, but dramatic chemistry never developed between these clandestine lovers/secret parents.

Cristina’s perennially angry father Carlo, the King of Sweden, was portrayed by Enea Scala. A local audience favourite, he possesses a clear tenor with dramatic strength and nice baritonal depths but occasionally strained top notes. The smaller roles were well cast with the promising young tenor Matteo Roma as Atlei, and sonorous bass Grigory Shkarupa as Giacomo, the intended but ill-fated husband for Cristina.

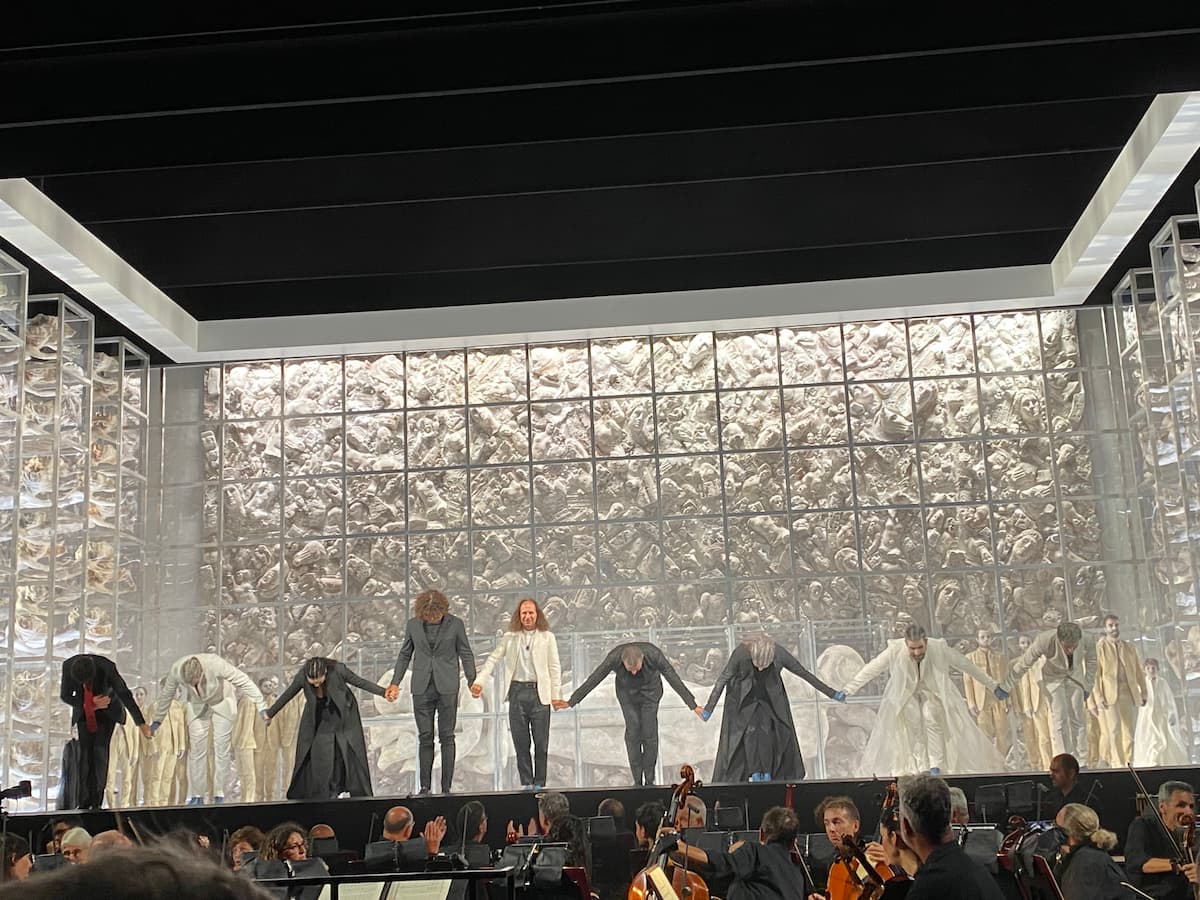

The opera is a gift to musicians. The same cannot be said of the story. Pity any director who tries to make this opera interesting. Stefano Poda, in his first outing at Pesaro, clearly benefited from financial and dramaturgical largesse and let it rip. The stage set was reminiscent of a massive white plaster version of Rodin’s Gates to Hell and the martial theme remained omnipresent. The chorus and dancers wore ghoulish white makeup and looked like a blend of zombies, skeletons, and Uncle Fester from the Addams Family. Occasionally they wore blue gloves for no apparent reason. Cubes with disjointed sculptural elements were moved around the stage to be finally joined together in a large sculpture that made no sense as a sole unit either. The dancers moved with stylized but meaningless animation, but above all, they were distracting.

Poda must be commended for his effort, but this opening night remained cold, joyless, consistently lugubrious, and ultimately unengaging. The audience might have been better served with a simple concert version.

© Rossini Opera Festival | Amati Bacciardi

Aureliano in Palmira, the festival’s second night, proved the perfect counterpoint. A reprise of Mario Martone’s low-budget production of 2014, this performance delivered the quality and frissons that Pesaro is famous for.

Sara Blanch as Zenobia and Raffaella Lupinacci as Arsace set off vocal and physical fireworks. The chemistry was incendiary. Both singers tackled the harrowingly challenging parts with precision, delicatesse, and beauty. Alexey Tatarintsev singing his first title role in Pesaro was a believable Aureliano, and gifted the audience with some sensational top notes, including a ringing high D.

Georges Petrou led the Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini. Story, music, and set worked together beautifully.

Productions and casts like these make the arduous trip to Pesaro worthwhile.

Performances attended: August 11, August 12, 2023

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter